By Sword and Plow: French Settlement in Algeria

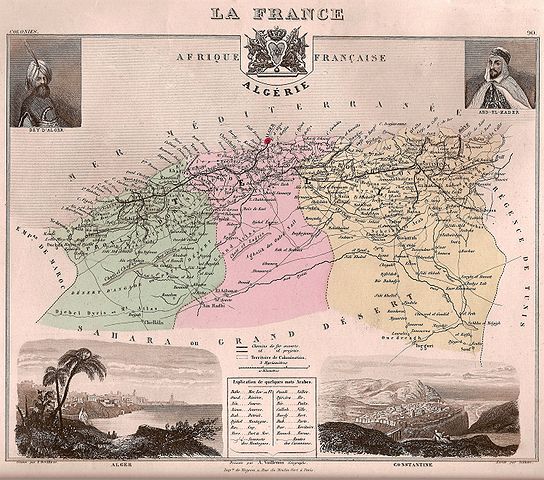

1880 map of French Algeria

The conquest of Algeria in 1830 was the beginning of France’s second period of imperial expansion. *

Like many colonial wars, the conquest became a sinkhole, eating armed forces and resources that many believed could better be used back home in France, which was in political turmoil following the July Revolution. (You could argue that France was in political turmoil for the entire nineteenth century, with a revolving door of revolution and restoration. But that’s a long story for another time.)

In the late 1830s, the commander in charge of the Algerian occupation and later Governor-General of French Algeria, General Thomas-Robert Bugeaud reached the conclusion that colonization was the only way to subdue Algeria, and consequently free up French troops needed to prevent social upheaval at home. Citing the example of Rome, he called for colonization on a grand scale: “Look for colons everywhere,” he urged. “Get them, whatever, the cost, from the towns, from the countryside, from among your neighbors…”

Drawn by the promise of fertile land, colons came from throughout the European Mediterranean and settled on land seized from its Algerian owners by a variety of legal stratagems.** The massive program of land distribution was made easier by the fact that the indigenous Algerian population was reduced by half between 1830 and 1850 as a result of the wars of conquest.

Algeria was formally integrated into the French national territory in 1848–after all it was only 400 miles away from Marseilles. European settlers (though not indigenous North Africans) were given the rights of French citizens, including representation in the parliament. By the end of World War II, when European imperialism was coming to an end, roughly one million settlers of European origin, known as pied noirs, had settled in Algeria–most of them not French. The colony’s economy was interwoven with that of the metropole and its cities were increasingly French in appearance and architecture.

Bugeaud had not planned on the fact that immigration would go both ways as it became easier to travel between Algeria and France. In the early twentieth century, Algerians began to migrate to France in search of jobs in the shipping, mining, construction and sugar refining industries, drawn by higher salaries and social benefits. The pied noirs complained bitterly about the loss of their work force. In response, the French government set up a department to control colonial recruitment. It did nothing to stem the flow of migrants. By the beginning of World War I, an estimated 80,000 Algerian colonial workers lived in France.*** During the war, roughly one third of Algeria’s male population were shipped to France as soldiers and workers to contribute to the war effort. 25,000 Algerian Muslims died on the battlefield defending France.

When the war was over, France made a concentrated effort to repatriate its Algerian soldiers–and to deport the Algerian workers that arrived before the war. (That’s how you say “Thanks for the help. Job well done.”) It didn’t work. Algerian migration to France increased. Perhaps because colonial expansion and land seizure in Algeria also increased. France soon had the largest Muslim population in Europe.

*France lost its first overseas empire at the end of the Seven Years’ War, known as the French and Indian Wars in the United States.

** My favorite? Deciding that the Arab owners “weren’t making good use of the land” and therefore should be relocated to land more suitable to their uses.

***It’s not clear to me if that number includes family members. It is likely that the migration patterns were similar to those of other ethnic groups in the late 19th and early 20th century: men traveled to the new country alone and sent money home to parents and wives. (Please note: at this point I’m making stuff up based on what I know about other places.)

****

Interesting. Deciding land owners aren’t making good use of the land is essentially the argument behind eminent domain in the USA, particularly the relatively recent precedent of government land-taking for private use via eminent domain. (Kelo v. City of New London, 2005) Kelo gives US federal, state, and local government agencies powers essentially the same as those of colonial France.

Hmm. I was thinking of parallels with the United States’ treatment of native peoples, not eminent domain. I’m going to have to think about this.

plus ça change…