Talking About Women’s History: A Whole Lot of Questions and an Answer w/ Julia Charles

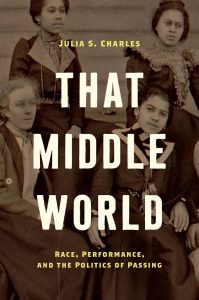

Julia S. Charles received her Ph.D. and an M.A. from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst from the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies. A proud two-time HBCU graduate, she received an M.A. in English and African American Literature from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University and a BA in English from Bennett College. Her newest book, That Middle World: Race, Performance, and the Politics of Passing, examines how mixed-race characters in American fiction performed race from the antebellum period through the New Negro Renaissance. Julia serves on the Board of Directors for FosterClub, an organization that connects, educates, and inspires youth in and from foster care in order to help them realize they personal potential. She is also the Co-Founder of The Loving Luggage Project, a community donation initiative that provides new luggage for youth in foster care to help ease their transitions through and out of foster care.

Take it away, Julia:

What path led you to Jessie Fauset’s story?

My path to Jessie Redmon Fauset was a beautiful one. It felt almost fortuitous. In graduate school in the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at UMass, I had been studying Charles W. Chesnutt, and I thought I would write my dissertation on him and his work. But through my classes I started to realize I was actually more interested in his depictions of mixed-race characters and the cultural phenomenon of racial passing. That same semester, one of my professors, A. Yemisi Jimoh, I believe it was, assigned Fauset’s Plum Bun to our class and I loved it.

Later in my program, Britt Rusert, who was also a professor of mine, arranged a visit to the special collections archives at UMass where I was able to thumb through the Du Bois Papers. In them, there were so many correspondences between Du Bois and Fauset, and then between Fauset and others on Du Bois’ behalf. There was one letter in particular that fascinated me most: it was from a young Fauset, then an English major at Cornell University, boldly asking Du Bois about a job, and complimenting him for having written The Souls of Black Folk. It was a letter that was short on words, but long on lessons for me. It was one of those days that you just know you have stumbled on something special. So, I went to find everything I could about her.

Why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

There are many women who have greatly impacted American history, but whose stories are buried in the work of the men of around them, or whose work is disregarded, lost, or simply forgotten. I think about legacies of Black women like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper whose name we know, but whose first book of poems, Forest Leaves, had been considered lost, until my friend from graduate school, Johanna Ortner, was simply doing the work of a graduate student—that is, researching—and recovered this important work. I think of how enriched I have been by the work of Zora Neale Hurston, and how, were it not for Alice Walker going in search of Hurston in 1975, I may never have been taught, encouraged, or validated by Hurston’s work. Both Harper and Hurston were brilliant in their day, and their work survives because someone was deliberately searching for them. And there are so many other Black women writers whose lives and works have suffered the same fate, Fauset being one of them. And so, here I am, doing the work of finding Fauset, and hopefully, giving her back to a people, a discipline, and indeed, a country that she worked so diligently to make better.

Jessie Fauset was well known in her time, but is largely overlooked now—not an unusual situation for women. Why do we tend to forget the roles women play in history?

During the New Negro Renaissance everyone who was anyone knew (and needed to know) Fauset. She was arguably the most influential women of the Renaissance, which is why in his biography, Langston Hughes (whose work Fauset was the first to print when she published “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in The Crisis in 1921) called her one of the three people who midwifed the “so-called New Negro literature into being.” Fauset was not just known during the Renaissance, she was well known and well respected. Much like Zora Neale Hurston, it wasn’t until after her career and death that she fell into relative obscurity.

But to answer the question, memory is often political, especially in literature and the arts. And the gatekeeps know well the politics of memory—that is, who gets to be remembered, how and why they are remembered. They are often powerful white men, leaders of institutions, archives, museums, and other spaces that are ostensibly intended to collect, preserve, and/or exhibit treasured historical artifacts. And so they control who gets remembered and the narrative of those folx lives. Thus, women are often viewed in terms of their service to those men, rather than their contributions to the nation more broadly or the world of arts and letters more specifically.

Writing about a historical figure like Jessie Fauset requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as your constant companion?

There’s a picture of Fauset that I love; it’s her senior portrait from when she was a student at Cornell University. This past Christmas, my fiancé commissioned a visual artist named Rodan who did an amazing colorized rendering of that image. It now hangs in my house. I walk past her every day. So, when you say this work—of life writing—“requires living with her . . .” it feels incredibly salient for me. In a lot of ways, Fauset has been a companion of mine since graduate school. I feel cheated that I didn’t know her before then. Having her as a companion now makes me feel both humbled and terrified. Humbled because who am I to get to share space with the ancestors this way? Why was I chosen—and I do feel chozen—to do this assignment? What have I done to deserve this rare treat? Yet, I feel petrified of failing her. I want to write her life so well that people begin to question the politics of memory. I want to people to ask why they haven’t known her before I facilitated their introduction to her life and work. What Alice Walker did with Zora Neale Hurston, I want to do for Jessie Redmon Fauset, who is just as worthy a subject. I want readers to question the politics of the archive, and so, in that way, I want to do her justice. And sometimes I wonder if there is enough space for me to do that.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

As you can imagine, all my reading lately has been in the genre of biography/life writing. And there are a few that jump out at me: There are a couple of new biographies of the great Black woman writer and activist Lorraine Hansberry that are, to my mind, outstanding. Former FLOTUS, Michelle Obama’s Becoming has fed me in several ways; not only is it beautifully written, but there is a level of transparency that I had not expected, especially where she discusses learning to have a life of her own outside of her powerful husband. Roxane Gay’s Hunger, which is not so much women’s history as it is a history of her body and its relationship or encounters with the rest of the world around her. But what a fantastic read! There are so many others, which might be more academic in tone, but I’m going to stick with these because they are each fantastic in their own right, but they have also been a boon to my understanding about the duty of the biographer in life writing.

If you could pick one woman from history to put in every high school history textbook, who would it be?

This is kind of a difficult question because there are people like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Pauline Hopkins, Anna Julia Cooper, Ida B. Wells, Nella Larsen, and, of course, Jessie Redmon Fauset. There are Black folx like Zora Neale Hurston, Audre Lorde, Pat Parker, June Jordan, Alice Walker, Toni Cade Bambara, The Combahee River Collective, and, my goodness, Toni Morrison, and Octavia Butler. The latter two who are arguably in a class all their own. And that doesn’t even include contemporary folx like, Jesmyn Ward, Tayari Jones, and Brit Bennett. Nor does it include children’s or YA writers like Mildred D. Taylor, Angie Thomas, and Jacqueline Woodson. And just look at the womxn I am leaving out with this short list. And this list only includes authors; it doesn’t even mention artists, entertainers, politicians, activists, or womxn from any other walk of life. Narrowing it to one would definitely be an exercise in futility for me.

Who are some of your favorite authors working in women’s history today?

Nareza Wright, author of Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century, and Deidre Cooper Owens, author of Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, are two of my favorites. I am also very much looking forward to Crystal Webster’s new book, Beyond the Boundaries of Childhood: African American Children in the Antebellum North, which will be out soon from UNC Press. I think all these authors are adding something valuable to our understanding about Black womanhood, even those of them who are dealing explicitly with girlhood studies.

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

The thing I find most challenging is the archive itself, but it is also the most exciting. History has not been kind to women, especially Black women. The ways in which it disregards them, dismisses them, misremembers their contributions, sometimes misgenders them, are all reflections of the archive’s failures. Yet, without even the parochial catalogs of the archives, even more would be lost. So, some of the challenge is rooted in the necessary confrontation with the formal archive and other spaces of memory. The other challenge is what to share of the subject’s life. There are too many instances of historical women’s contributions being obscured by or reduced to who they were intimate with or who they worked for. The exciting part is figuring out what to include and what to keep private for Fauset.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

Of course, Women’s History Month is incredibly important. In a lot of ways, it does what I am suggesting in confronting the archive. The more women we learn about through observations like Women’s History Month, the more likely we are to change the global tendency toward erasure of women.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

Without giving too much away, one of the most surprising things I have found is the sheer volume of correspondences between Fauset and anyone who was anyone during the New Negro Renaissance. It just demonstrates that her sphere of influence was so vast.

Another question for Pamela. What are your top 5 books about women and why?

This is as tough as choosing one woman to put into high school history books! Here are five books about women that I loved and that stuck in my head long after the fact:

1. Margalit Fox’s The Riddle of the Labyrinth: The Quest to Crack an Ancient Code was my first up-close look at a woman’s contributions to a discovery being swept aside in favor of a male colleague. Infuriating and illuminating.

2. Antonia Fraser’s The Warrior Queens introduced me to the idea that women “fought, literally fought, as a normal part of the army in far more epochs and far more civilizations than is generally appreciated.” She set me on the road that led to Women Warriors, thirty years later.

3. Matthew Goodman’s Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World held me spellbound. (I must admit, I was rooting for Bisland all the way.)

4. Together Sarah Gristwood’s Blood Sisters; The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses and Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe transformed the way I think about women’s roles in medieval and early modern Europen power politics. (I’m going to cheat and count them as one book.)

[Despite appearances, I did not step to my bookshelves, which are organized alphabetically by authors’ last names, and randomly pull books off the shelf.]

5. I know I’ve mentioned them before, but I owe a debt of gratitude to the authors who wrote biographies for young girls about smart and/or tough women who sidestepped (or kicked their way through) society’s boundaries and accomplished stuff no one thought they could accomplish. A handful of those books found their way to my school library when I was in fifth or sixth grade. They were a revelation.

* * *

Want to know more about Julia Charles and her work?

Check out her faculty profile: https://cla.auburn.edu/english/people/professorial-faculty/julia-charles/

* * *

Come back tomorrow, when we go out with a bang with three questions and a answer with best-selling historical novelist Renée Rosen.

Can you imagine how exciting it must have been to discover a lost work while researching? Makes me want to camp out at a library. Very enjoyable interview.

Research is always a thrill!