In Which I Stand Corrected

In a recent post, writing about the Civilian Conservation Corps, which provided jobs and job training for some three million unemployed men between the ages of 18 and 25 from 1933 and 1942, I stated that that there was nothing similar for young women. A regular and valued reader of this blog immediately and politely informed me that in fact there was a female equivalent of the CCC, called the She She She by its critics. It wasn’t as big or as well-known as the CCC, but it did exist. He then gave me a link to an excellent article on the subject on the New England Historical Society website. *

- In Maine

- In New Jersey

Red-faced, and fascinated, I headed off to find out more. The NEHS article provided me with links, which provided me with more links and I spent a happy afternoon going down the historical rabbit hole. I’ve got to say, after working my way through the readily available material on the program, I’m not surprised that I had never heard of it.

The “She She She” wasn’t actually a single program with a unified curriculum or set of goals. It may not have even had an umbrella name beyond the description “Resident Schools and Educational Camps for Unemployed Women” or at least I have not be able to find one.** Most of the studies I have read on the program refer to it as “the She She She camps,” using the derisive name given to it by its critics, suggesting that their authors were also not able to find an umbrella name for the program.

Soon after FDR signed the bill creating the CCC into law on April 1, 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt suggested the establishment of a similar program for women. FDR turned the idea over to Harry Hopkins, who was his right hand man on New Deal relief programs.

At first, it looked like Hopkins was going to make it happen. The first camp for unemployed women, Camp Tera, opened as an experiment on June 10, 1933. When Eleanor visited the camp a month later, expecting to see 200 young women, she found only 20. That November, when it was clear that Hopkins was doing little to create the camps or otherwise help unemployed women, she organized a White House Conference on Women to advocate for New Deal programs for women. Under pressure from the First Lady, Hopkins turned the problem over to Hilda Worthington Smith, the New Deal’s education specialist.

Hopkins’ lack of interest in the program was reflected in Federal Emergency Relief Administration (later the WPA) as a whole. (One FERA official warned Smith that there would be serious discipline problems if groups of women lived together.***) Bad attitudes about working women weren’t limited to FERA. At the start of the Great Depression, women made up 25% of the American workforce, but the general public believed that women were inherently temporary employees who would leave the work force when they got married. **** Worse, many believed that jobs programs for woman came at the expense of jobs for men, who, after all, were the real breadwinners.

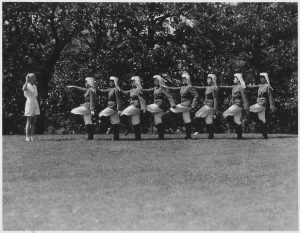

With support from Eleanor Roosevelt, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, and other prominent women, Smith managed to get limited federal financial support for camps for women from Hopkins despite opposition from FERA in general and CCC administrators in particular. Responsibility for the camps themselves was turned over to individual states to implement. The camps were housed in private estates, country clubs, summer resorts, unused YWCA campgrounds and abandoned school buildings. The curriculum of each camp depended on local resources and opinions and residence at the camps varied from six weeks to three months. At one camp, housed at the summer home of the president of the Temple University Women’s Club, the enrollees spent twelve weeks taking classes in shorthand, typing, bookkeeping, business English and home economics. But in other camps, women produced Braille materials and hospital dressings, repaired toys, put on plays, and learned “domestic arts.” One camp even offered a course called “Charm by Choice” —a far cry from the job skills and general education offered in the CCC camps.

- In Minnesota

- In Maine

This is how civil rights activist Pauli Murray, who attended Camp Tera in the fall of 1933, described the experience: “It was little more than a recreational camp for adult women at the time I was there, since it offered no work experience beyond our camp duties and was only one step removed from the dole. Yet for me, as for most other women in the camp, it provided a sanctuary from the pressures of unemployed city life.” At least the camps provided women who were underfed and exhausted when they arrived with three meals a day for several weeks.

Smith had hoped to open 150 camps and schools and provide work and training for 15,000 young women. Between 1933 and 1937, the program opened 90 centers and enrolled roughly 8,000 women. In 1935 alone, the CCC had 500,000 men in 2,600 camps.

I’ll let you do the math.

*I love it when readers send me down a new research path, even when it starts because I make a mistake. Y’all are the best.

**Under the circumstances, I’m going to be cautious about what I say on this subject.

*** Grrr. Don’t get me started.

**** A classic Catch 22: often women were required to leave the workforce when they married. Double grr.

Really enjoyed this post! I had certainly not heard of this project.