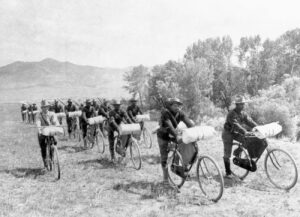

Buffalo Soldiers on Bicycles

This is one of my favorite stories from our visit to Fort Snelling:

After the American Civil War, Congress created six regiments of Black soldiers, led for the most part by white officers, known informally as Buffalo Soldiers.[1] One of those regiments , the 25th Black Infantry, was posted at Fort Snelling in 1880. Eight years later they were transferred to Fort Missoula, Montana, where this story took place.

****

At the end of the nineteenth century, bicycles were all the rage. The bicycle was as popular with members of the army as it was with the general public. In 1894, roughly half the personnel at Fort Missoula had bicycles and the fort was holding informal bicycle drills, which included members of the 25th Infantry.

In 1896, Lieutenant James Moss, commander of the 25th Infantry Regiment in Missoula,[2] took the idea one step further and proposed that the military could replace horses with bicycles for some operations.[3] Bicycles, unlike horses, did not need food water or rest. They were virtually noiseless. He was not the first Army officer to suggest the use of bicycles by the military. Several years previously, then Major General Nelson A. Miles tested the possibility of using bicycle couriers. (Among other things, he reported, his bicycle trials demonstrated the wretched condition of American roads.)

Moss’s request to organize an experiment with bicycles was approved on May 12, 1896. A little over a year later, after months of training that included daily rides of fifteen to forty miles and two longer excursions to Lake McDonald and Yosemite during which they carried rifles, rations, and equipment, the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps, also known as the Iron Riders were ready for a much longer expedition. This ride was designed to demonstrate to the Army leadership that bicycles would be an efficient way to transport soldiers in time of war. Moss described the corps as “bubbling over with enthusiasm . . . about as fine a looking and well-disciplined a lot as could be found anywhere in the United States Army.”

On June 14, 1897, twenty soldiers, two officers and one reporter set out on a 1,900 mile bike ride from Fort Missoula to Saint Louis. The route took them through a variety of terrain and climates. Averaging 50 miles a day for 41 days, on bikes specially made for them by Spaulding Bicycle Company, they rode on unpaved roads and occasionally on railroad tracks. (Not a fun surface to ride on, as anyone who ever rode a bicycle can imagine.) They crossed mountains and forded rivers. They rode through snow, sleet, rain, and oppressive heat. Sometimes the ground was so muddy and slippery that they had to push their bikes for several miles.

By the time the riders reached Missouri, the story had caught the public imagination. When the members of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps reached St. Louis on July 24, almost 1000 local cyclists rode out to meet them. Crowds lined the streets to greet them as they rode into the city, In the following days, tens of thousands St. Lois residents visited the corps’ camp in Forrest Park and watched them perform exhibition drills.

The discovery of gold in Alaska replaced the story of the bicycling Buffalo Soldiers in the nation’s headlines. The corps was disbanded once it reached Missoula, traveling this time by train. Lieutenant Moss remained optimistic about the value of the bicycle to the military in his report to the War Department and requested permission to organize a second bicycle corp. But with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, the military moved further experiments with bicycles to a back shelf.

The 25th Infantry Regiment left Fort Missoula for training camps in Georgia and Florid. From there, the unit saw action in Cuba and distinguished itself in the Spanish-American War. Moss returned from Cuba and proposed a company of 100 soldiers on bicycles to patrol Havana once it was under the occupation of American troops. His proposal was rejected.

By World War I, the Model-T had replaced the bicycle as the hot new mode of transportation in the eyes of both the public and the military.

[1] By some accounts, the Native Americans against whom they fought gave them the nickname because their curly hair resembled buffalo manes and because of their fierce nature. Maybe. Maybe not.

[2] Racism was rampant in the army at the time. Moss graduated last in his class at West Point and had no choice in where he was assigned. As he later said in a speech in his home town in Louisiana “ Being a Southern boy I did not at first, I must admit, like the idea of serving with colored troops.” With time, he changed his mind and was proud to have them under his command.

[3] This was not as revolutionary an idea as is sometimes claimed. Italy created a military bicycle unit, which was used for reconnaissance and courier services, as early as 1875. Other European countries followed Italy’s lead. By 1890, France, Austria, Switzerland and Germany all had bicycle units.