In These Times: Living in Britain Through Napoleon’s Wars

Even the most eclectic history buff has periods that draw her back time and time again. if you've spent much time here at the Margins you know the late eighteenth century is one of those times for me. Regency England and Revolutionary France, colonial expansion in India and losses in North American, Enlightenment thought and the roots of Romanticism--all call my name.

Since this is the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, I'll be spending more time than usual thinking/reading/talking about the long eighteenth century.* I suspect I won't be the only one. In fact, I'll bet the on-line discussion this July will equal that surrounding last year's centennial anniversary of the assassination of the Grand Duke Ferdinand at Sarajevo.**

Uglow describes In These Times as "a crowd biography". For much of her career, Uglow has looked at the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries through the lens of individual lives. With In These Times, she expands her talent for biography into a broader account of how the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars affected those who remained at home. The big names of British history--William Pitt and Willaim Cobbett, Nelson and Wellington, Sir Walter Scott and Jane Austen--appear in their proper places. But Uglow focuses on less celebrated lives from all levels of society, from factory boy to aristocratic lady, as recorded in letters, memoirs, diaries, and parish records.

In This Times is not another version of "daily life in the time of".*** Instead Uglow looks at how twenty-two years of constant warfare shaped society in fundamental ways. She not only describes direct effects of war such as enlistment practices and the economic impact of government military contracts; she also places events that are normally described in terms of their domestic impact, such as the social disruptions caused by the Industrial Revolution, within the context of war. She looks at newspaper distribution, shoe manufacturing, the impact of war loans on private banking and the ethical dilemmas of Quaker gun manufacturers,

Depicting a society in which war is as pervasive as permanent bad weather, In These Times combines social and military history in a manner that will appeal to readers of both.

*Roughly 1688 to 1815, or 1832 depending on which historian you talk to. Sometimes centuries are an awkward time division when you’re talking about historical events instead of the calendar. .

** Normally I'd link to my own post on the subject. But this one is much better: Two Bullets, Eight Million Dead.

*** If that's what you're looking for, may I recommend Jane Austen's England?

The heart of this post previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

Rabindranath Tagore: Poet, Nobel Laureate, Indian Nationalist

Few people in the modern world attain the degree of celebrity that allows them to be known by a single name: Napoleon, Gandhi, Madonna. Even those who reach single-name celebrity in their own country may be largely unknown to the rest of the world. Take the example of Bengali poet, novelist and composer Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) who is known in India simply as Kabi, the Poet. Every Bengali language speaker, all 250 million of them, knows a line or two of his poetry. By contrast, most westerners know Tagore only (if at all) as the recipient of the Nobel Prize, but have no sense of either the poetry for which he won the award or his broader career.

Born in 1861, to a prominent Calcutta family, Tagore was a leading member of the late nineteenth century literary, cultural and religious reform movement known as the Bengali Renaissance. He is generally considered the father of the modern Indian short story, he pioneered the use of colloquial Bengali in literature, and created a new genre of popular contemporary music known as rabindra-sangeet that draws on traditional Bengali folk and devotional music as well as Western folk melodies. (After independence, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh all chose songs by Tagore as their national anthems.) He is often compared to Tolstoy, and seen as a precursor to Gandhi,

Tagore became famous as a writer when he published his first novel in 1880, at the age of nineteen. In 1905, he became involved in nationalist politics after the British Viceroy, Lord Curzon, divided Bengal province in two, effectively cutting the power base of the Bengali elite who headed the early Indian nationalist movement. In response, Indian nationalists boycotted British goods and institutions, a protest known as the Swadeshi (of our own country) movement. At first Tagore threw himself into the Swadeshi cause, leading protest meetings, writing political pamphlets and composing patriotic songs. His initial enthusiasm for the movement failed when the Bengali population was torn by increasing communal violence between Hindus and Muslims. Despite bitter criticism from nationalist activists., he withdrew from the movement in 1907, concentrating instead on experiments in economic development and education in the villages on his estate.

Tagore made the leap from national to international fame in a single year with the help of one important admirer. He traveled to London in 1912 with a collection of English translations of 100 of his poems, which became the collection known as Gitanjali. While he was in London, he met William Butler Yeats, who became a passionate advocate of his poetry. In part as a result of Yeats’ championship, Tagore received the Nobel Prize for literature on November 13, 1913. Tagore’s Nobel Prize sparked a brief, but intense, period of popular and critical interest in his work in the west. It was soon translated into many languages, including a French translation by André Gide and a Russian translation by Boris Pasternak. Tagore himself became an international literary celebrity, traveling around the world on lecture tours and revered as the embodiment of the mystical east. His critics accused him of collaboration with the enemy, especially after he was knighted by King George V in 1915.

Accusations that Tagore was an imperial collaborator ended in 1919. On April 13, Brigadier General Reginald Dwyer ordered soldiers under his command to fire on an unarmed crowd of 10,000 Indians who had assembled in an enclosed public park in the Punjabi city of Amritsar to celebrate a Hindu religious festival--an event that became known as the Amritsar Massacre. The soldiers fired 1650 rounds in ten minutes, killing 400 and wounding more than 1000. Tagore resigned his knighthood in protest.

For the rest of his life, Tagore criticized British rule in India while refusing to reject Western civilization, a position that often placed him in opposition to Gandhi.

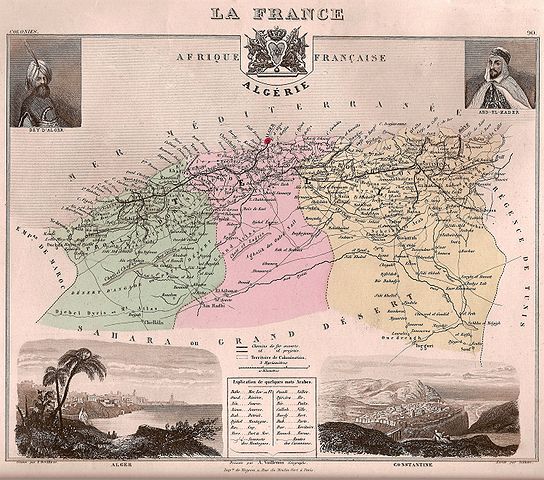

By Sword and Plow: French Settlement in Algeria

1880 map of French Algeria

The conquest of Algeria in 1830 was the beginning of France’s second period of imperial expansion. *

Like many colonial wars, the conquest became a sinkhole, eating armed forces and resources that many believed could better be used back home in France, which was in political turmoil following the July Revolution. (You could argue that France was in political turmoil for the entire nineteenth century, with a revolving door of revolution and restoration. But that’s a long story for another time.)

In the late 1830s, the commander in charge of the Algerian occupation and later Governor-General of French Algeria, General Thomas-Robert Bugeaud reached the conclusion that colonization was the only way to subdue Algeria, and consequently free up French troops needed to prevent social upheaval at home. Citing the example of Rome, he called for colonization on a grand scale: “Look for colons everywhere,” he urged. “Get them, whatever, the cost, from the towns, from the countryside, from among your neighbors…”

Drawn by the promise of fertile land, colons came from throughout the European Mediterranean and settled on land seized from its Algerian owners by a variety of legal stratagems.** The massive program of land distribution was made easier by the fact that the indigenous Algerian population was reduced by half between 1830 and 1850 as a result of the wars of conquest.

Algeria was formally integrated into the French national territory in 1848--after all it was only 400 miles away from Marseilles. European settlers (though not indigenous North Africans) were given the rights of French citizens, including representation in the parliament. By the end of World War II, when European imperialism was coming to an end, roughly one million settlers of European origin, known as pied noirs, had settled in Algeria--most of them not French. The colony’s economy was interwoven with that of the metropole and its cities were increasingly French in appearance and architecture.

Bugeaud had not planned on the fact that immigration would go both ways as it became easier to travel between Algeria and France. In the early twentieth century, Algerians began to migrate to France in search of jobs in the shipping, mining, construction and sugar refining industries, drawn by higher salaries and social benefits. The pied noirs complained bitterly about the loss of their work force. In response, the French government set up a department to control colonial recruitment. It did nothing to stem the flow of migrants. By the beginning of World War I, an estimated 80,000 Algerian colonial workers lived in France.*** During the war, roughly one third of Algeria’s male population were shipped to France as soldiers and workers to contribute to the war effort. 25,000 Algerian Muslims died on the battlefield defending France.

When the war was over, France made a concentrated effort to repatriate its Algerian soldiers--and to deport the Algerian workers that arrived before the war. (That's how you say "Thanks for the help. Job well done.") It didn’t work. Algerian migration to France increased. Perhaps because colonial expansion and land seizure in Algeria also increased. France soon had the largest Muslim population in Europe.

*France lost its first overseas empire at the end of the Seven Years’ War, known as the French and Indian Wars in the United States.

** My favorite? Deciding that the Arab owners “weren’t making good use of the land” and therefore should be relocated to land more suitable to their uses.

***It’s not clear to me if that number includes family members. It is likely that the migration patterns were similar to those of other ethnic groups in the late 19th and early 20th century: men traveled to the new country alone and sent money home to parents and wives. (Please note: at this point I’m making stuff up based on what I know about other places.)

****