La Folie Baudelaire

In La Folie Baudelaire Roberto Calasso describes the life, work, and world of symbolist poet Charles Baudelaire in terms of an image borrowed from nineteenth century French critic Charles Saint-Beuve: the "highly decorated, highly tormented but graceful" architectural extravagance known as a garden folly. Saint-Beuve used the image to disparage Baudelaire's work. In Calasso's hands it becomes high praise.

Part of an on-going exploration of the nature of modernity that began with the acclaimed Ruin of Kasch (1983), La Folie Baudelaire is not a biography of Baudelaire, though the reader will learn much about the poet's life along the way. Instead Calasso uses Baudelaire and his writing as a lens through which to consider the literary and artistic world of nineteenth century Paris. Baudelaire leads Calasso and the reader to poets, painters, and prostitutes, to Gautier and Flaubert, to Ingres, Delacroix, and Degas, to romanticism, decadence, symbolism and, ultimately, modernity.

La Folie Baudelaire is fascinating, but it is not an easy read. Even the best-educated reader may want to keep a dictionary close at hand. Calasso's style is both erudite and lyrical--as allusive as that of the poet who stands at the center of the work. Instead of a narrative history, the work is constructed as a series of loosely linked meditations that move back and forth through time--an innovative and eccentric format developed by Calasso in his earlier works. Despite its challenges, any reader interested in the period--or the poet--will find La Folie Baudelaire worth the effort.

This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

Road Trip Through History: The Battle of Hastings

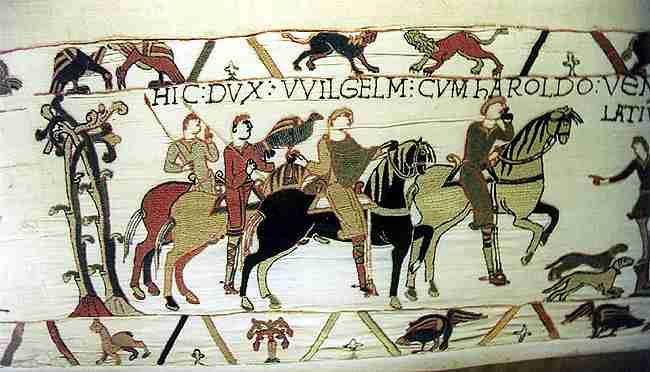

Image courtesy of Antonio Borillo

On October 13, thousands of history enthusiasts from around the world arrived at the British town of Battle to re-enact the Battle of Hastings. (You know, William the Conqueror, 1066, and all that.)

My Own True Love and I weren't there.* Just as well. The weather was cold and wet. The battlefield conditions were so muddy that the organizers called off the second day of the battle because the ground was too muddy for vehicles to get in and out. (I suspect any number of Anglo-Saxon and Norman soldiers at the original battle would have been pleased if someone had called off the second day of the real battle.)

When we arrived, a week later, the battlefield was still a muddy mess. We happily went through the excellent introductory exhibit, learning about Anglo-Saxon England, the Duchy of Normandy, and why William the Bastard of Normandy** thought he had a claim to the English crown.***

Then we headed to the battlefield, audio tours in hand. Before we got to the first point on the tour, we were slipping in the mud on the path. My Own True Love's shoes sprang a leak. Defeated by the mud, we retreated to the café, where we drank coffee, listened to our audio tours, and envied the rubber boots worn by the squadrons of British school children trooping past.

You can get a detailed account of the battle here. These are the elements that struck me:

- Both sides were descendents of Viking conquerors. The rulers of England were the descendents of King Canute of Denmark. The Normans were Norwegian Vikings with a French accent.

- The battle was a classic stand off between infantry and armed horseman: immovable object vs. irresistible force.. The English army, on foot, depended on the strength of its shield wall. The Normans enjoyed the mobility of cavalry. William stumbled on a tactic that the Mongols (armed horsemen par excellence) would later use to confound Western armies. When his men panicked and retreated, exultant English troops broke out of formation to pursue them. William saw what was happening and ordered his flank to cut the English off. The pursuers were surrounded and slaughtered.. The first time was an accident. William learned; apparently the English didn't. When William ordered a feigned retreat to replicate his success, the English pursued again and were slaughtered again.

- The Battle of Hastings changed history, but it wasn't the only time France invaded England. Who knew?

Next stop, Brighton.

* We missed several special history nerd events as we drove along Britain's southeast coast--always a week too late or a week too early. We did, however, manage to arrive in Bath on the day of a major rugby match.

** The name was a legal description, not a character assessment.

*** William was a shirttail relative to Edward the Confessor, whose death in 1066 was the catalyst for the invasion. William's great grandfather was Edward's maternal grandfather.