Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Richard Miller

Richard Joel Miller was born in Portman Square in London, England. He developed an interest in chemistry when his father gave him a chemistry set for his fifth birthday. Following an unfortunate series of events involving explosions in the family garage, his interests (much to his parents’ relief) shifted to the finer points of biochemistry, and a desire to use science to understand the workings of the brain. Richard obtained his PhD from Cambridge University and then joined the faculty of the University of Chicago in 1975. After 25 years he transferred to the Department of Pharmacology at Northwestern University, where he is now Professor Emeritus.

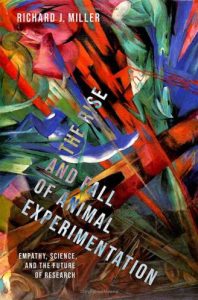

Richard has published over five hundred scientific papers and four books in the areas of biochemistry, physiology, pharmacology, and neuroscience. In his latest book, The Rise and Fall of Animal Experimentation (OUP), Richard looks back over decades of research, examining the use of animals in science and exploring: Why do we do it? Is it successful, i.e. does it further translational medicine? Is it ethical? He also discusses the ever-increasing use and potential of human stem cells and related technologies in creating experimental models, making animal-based research ultimately obsolete.

Take it away, Richard!

Did you expect women to play a role in your study of animal experimentation when you began your work?

What was the most surprising thing you've found about women’s involvement in animal rights activists while doing historical research for your work?

When I first began this project I didn’t really have any expectations about the role of women in the history of animal experimentation and the animal rights movement. I must admit that it wasn’t something I had really thought about. But, as it turned out, there was a lot to learn. Of course, to begin with, as you go through the history of animal experimentation which began in antiquity, you only read about men. It’s men who performed the experiments. Moreover, nobody had much to say about animal rights. Once you get to the 16th century, there was Montaigne who wrote eloquently about the reasons why we should respect the intelligence and feelings of animals. Then in the 17th century there was Margaret Cavendish, the first women to write about these topics, followed by others in the 18th century. Suddenly, in the 19th century, there were a huge number of women involved in the animal rights movement; actually, I think it was mostly women! Why was this?

The animal rights movement started in England where the first laws to protect animals were presented to Parliament at the start of the 19th century, although none of them got anywhere for several decades. There weren’t any women Members of Parliament (MPs) in those days. On the other hand, women were starting to speak out about their roles in society in general and so became associated with a whole group of causes that concerned “rights”, including the anti-slavery movement, animal rights and suffragettism. Most of the women you read about were simultaneously active in all these movements. They had to find ways of supporting their beliefs outside of Parliament. Hence, it was women who founded many of the animal welfare movements such as the societies that opposed vivisection. In fact, it was a woman named Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904), who initiated the antivivisection movement in Great Britain. A prolific author, she published numerous essays on animal rights and feminist philosophy. In 1875, she founded the Victoria Street Society which became the Society for Protection of Animals against Vivisection. The efforts to promote animal rights in England soon spread to the USA and the Continent. Queen Victoria, who was a great animal lover, joined the antivivisection movement, which gave it a lot of credibility and made it fashionable.

What really surprised me was just how radical these women were both in the context of animal welfare and suffragettism. These days you hear about members of groups like PETA acting as agent provocateurs, infiltrating laboratories, and reporting on what they see. The female antivivisectionists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries did precisely the same things. There was a famous incident when two women antivivisectionists infiltrated a medical school demonstration where a dog was being dissected and then wrote a book about it called The Shambles of Science. The book provoked all kinds of grass roots activism. A statue was put up in Battersea Park celebrating the dog, leading to riots involving thousands of people who were pro or anti-vivisection. This became known as “The Brown Dog Affair”. These women really put themselves in harm’s way and were incredibly brave and energetic in pursuing their goals. It was fantastic. I never knew anything about all of this, and I was extremely impressed.

You write about a number of women ranging from the seventeenth century polymath Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle through twentieth century animal rights activists. Do you have a favorite, or two?

Well, yes, you do have to like “Mad Madge” (Margaret Cavendish) in the 17th century, for one. She was an amazing person. She wrote about cruelty to animals, and did a lot of other things as well, including writing the first science fiction novel-The Blazing World, together with a great deal of poetry and essays on natural philosophy (science). Notably she published her works under her own name, something that was unheard of for women at that time. She was fearless. She made waves. Everybody turned out to see what she was wearing, and they were frequently shocked. Once she was even seen wearing a man’s coat! People just couldn’t believe it. She was the Vivienne Westwood of her day; a punk goddess, avant la lettre.

Margaret Cavendish was also the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, the world’s original and most prestigious scientific society where she engaged with some of the greatest scientists of the day like Sir Robert Boyle. In the 18th century, following Cavendish, other women began to publish under their own names and would comment negatively on the use of animals in laboratories. Susanna Centlivre, for example, in her play The Basset Table, introduced Valeria, a virtuosa (female scientist) who performs cruel experiments on dogs.

Less famous than Margaret Cavendish, but of great importance, was Lizzy Lind Of Hageby. She was born in Sweden in 1878 to an aristocratic and extremely wealthy family but settled in England following her education at Cheltenham ladies’ college. Lizzy lived the rest of her life in England, mostly in London, where she shared her home with another women, Leisa Schartau, also originally from Sweden. Leisa shared Lizzy’s views on many topics. For example, they wrote about the training of medical students:

“What is the influence on students who attend demonstrations where live animals, cats and dogs and rabbits, are cut open before the class to demonstrate some scientific theory? There are very few who would not acknowledge that it is far, far better to make boys and girls humane and merciful men and women, with hearts and well as heads, than to make them learned and intellectual, but heartless and cruel.”

It should be remembered that ideas connected with spiritualism and theosophy were extraordinarily influential in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These included the goal of uniting all men and women equally at the spiritual level in their search for divine wisdom. Both Lizzy, Leisa and the majority of their female associates were devoted followers of Henrietta Blavatsky and her theosophical ideas. Madame Blavatsky’s successor as head of the Theosophical society, Annie Bessant, was also an active participant in the drive for animal rights. Indeed, many of the women who were active at this time promoted “rights” of many types as well as other ideas. These included human rights, animal rights, suffragettism, theosophy and spiritualism. They also invariably promoted other ideas which would seem outmoded to us today, such as strong opposition to vaccination (yes, it’s nothing new) and germ theory. They also shared a general belief in animal telepathy.

Lizzy was an absolutely incredible person. She had a brilliant intellect, and was indefatigable. She founded the Animal Defense and Antivivisection Society and helped to found similar societies all over the world, organizing many international meetings on the topic of animal rights. She was extremely active at the personal level and often put herself in danger physically in public in support of the causes she believed in; she was involved in the riots that accompanied the Brown Dog Affair, as discussed above. She would also give frequent public lectures and debated representatives of universities and hospitals who supported vivisection. She always won these debates as she was an extremely effective public speaker. And her achievements in the sphere of animal rights weren’t the only things she did. She had great sympathy for suffering of all sorts, both humans and animals, and, for example, went to Europe during the First World War where she opened institutions to take care of wounded soldiers and others to rehabilitate horses. If that wasn’t enough, she wrote numerous books, including the first biography of her Swedish compatriot the playwright August Strindberg. When she died in 1963, she left her fortune to the Animal Defense Trust, which she founded, and which continues to offer grants for animal-protection issues, so that her influence lives on today. Just thinking about all her accomplishments leaves me breathless.

What unsung woman activist from the past would you most like to read a biography of, and why?

There are certainly a large number of women whose roles in the history of the animal rights movement have not been well researched, but there is one in particular I would like to mention. Before I do, however, let me explain the situation with respect to the use of animals for laboratory research in 19th century science. Using animals for vivisection is something that goes back to the work of people like William Harvey in the 17th century when he discovered the circulation of the blood; his research was based primarily on animal vivisection. In the 17th century science was only practiced by relatively few wealthy gentlemen like Harvey. But, by the 19th century science had become a profession and so the number of scientists had increased enormously. The tradition of vivisection was mostly advanced in France. The most important of all the French physiologists in the 19th century was Claude Bernard. He is considered one of the greatest physiologists of all time and he introduced many key concepts into biology and medicine. One key idea was that of homeostatic regulation, that tissues always respond to changes in other tissues in an attempt to maintain a state of equilibrium. Bernard’s most productive experimental paradigm was vivisection, particularly of dogs. Nevertheless, whatever his scientific achievements, there is no doubt as to the profound cruelty of the procedures he carried out. Indeed, the burgeoning anti-vivisection movement of the time, particularly in England, took notice of what Bernard was doing and his work became controversial.

One thing to note is that Bernard didn’t come from a rich family and his scientific research cost a good deal of money. So, he made sure that he married a wealthy woman. In those days, once married, all of a wife’s money became the property of her husband. The woman Bernard married in 1843 was Marie-Françoise (“Fanny”) Bernard (née Martin) whose dowry was used to finance his research. It was an arranged marriage but, unfortunately, vivisection became a point of contention between the couple. Fanny and the couple’s two daughters, Marie-Claude (1849-1922) and Jeanne Henriette (1847-1923) were absolutely horrified by Bernard’s nightly expeditions around Paris trapping stray animals for his vivisection studies. It is said that they once discovered a neighbor’s missing dog on his operating table. The couple ended up divorcing, something that was very difficult to do in a Catholic country like France. Fanny Martin became committed to the animal rights cause, joining the Société Protectrice des Animaux (Society for the Protection of Animals), which was founded in 1846. Fanny Martin and her daughters also opened and ran an animal shelter where they would rescue dogs and cats. Fanny and her youngest daughter helped to create a dog cemetery in Asnières and were active in the emerging French antivivisection movement in many ways. Fanny Martin became one of her ex-husband’s fiercest opponents.

Unfortunately, history has ignored Fanny Martin. She is really only discussed in the context of the fact that she was Claude Bernard’s wife and her antivivisection sympathies, from the point of view of scientists, are considered to be aberrations. However, Fanny Martin exhibited incredible bravery in opposing her husband at a time when such thing was simply not done. Moreover, it wasn’t just the fact that she stood up personally against Claude Bernard and the whole of the scientific edifice that supported animal experimentation, but the fact that she was extremely active in promoting the movement in France. Sadly, nobody has written a proper biography of Fanny Martin. It’s a great shame because she was really a hero of the animal rights movement.

A question from Richard: As we have seen, women played an essential role in the birth of the animal rights movement , particularly promoting animal issues outside the government (e.g. Parliament).Do you think that women have a unique role to play in the animal rights movement these days, considering the position of women in 21st century society?

[Pamela takes a deep breath and blows it out slowly] I know so little about this subject that I am diffident about offering an opinion at all. But here goes, based on the largely female staffs of the veterinary offices and animal shelters that I know, I suspect that women also make up a disproportionately large percentagel of the animal rights movement today. But honestly, I’m just riffing here.

***

Want to know more about Richard Miller and his work?

Check out his website: https://richardjmillerscientist.com/

Check out his LinkedIn profile: Richard J Miller

Follow him on Mastodon: @richardjmiller@mastondon.social

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with Marcia Biederman, author of The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill. Abortion, Death, and Concealment in Victorian New England

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Sarah Percy

Sarah Percy is associate professor at the University of Queensland. The author of Mercenaries and Forgotten Warriors: The Long History of Women in Combat, she completed her MPhil and DPhil as a Commonwealth Scholar at Balliol College, Oxford. She lives in Brisbane, Australia.

Take it away, Sarah!

What inspired you to write Forgotten Warriors?

A historical puzzle got me thinking about the role women had played in combat in history. The first one is that the US had female astronauts thirty years before they had women in combat. Women were allowed to be armed police officers (and therefore shoot to kill) and were allowed into a variety of dangerous or previously all male jobs in the 1970s. But for some reason, combat remained about the only profession you can think of from which women were actually banned in the 21st century! I wanted to know why this was the case – especially in a context where a powerful women’s rights movement, including many lawsuits to break down barriers for women, had opened doors everywhere else. What was special about combat? To find out the answer to this puzzle, I had to understand what women had done on the battlefields of the past, which only made the puzzle more interesting – because there is plenty of evidence that women engaged in combat with great success. So the book became about finding out the answer to my puzzle, and telling the story of women in combat.

In Forgotten Warriors, you literally explore “the long history of women in combat. ” How did you decide which women to include?

One of the great joys of researching this book was finding out about all the amazing women combat fighters of the past. There are so many it wasn’t easy to choose, especially because Forgotten Warriors is not a compendium of women fighters (other people, including you, have done this so well!). But in a way, this made it easier. My goal with the book is to demonstrate that women fighters have been an integral part of broader military history, and consider how understanding their stories illuminates this conventional history in different ways. So I chose women whose stories helped me demonstrate the key arguments of the book: that women have always fought, but often been overlooked or even had their service deliberately forgotten, and that women’s military contributions have often been belittled because for whatever reason they are not considered to be fighting in ‘proper’ wars or on ‘real’ battlefields. One of the things I found most interesting was that many of the women in the book were actually pretty ordinary. They weren’t, in their pre-war lives, notably physically imposing. But when given the opportunity to fight, they excelled. I loved the stories of the ordinary British women who were recruited for the Special Operation Executive, and sent to fight behind enemy lines in occupied France. These women were chosen because they spoke French fluently and could go undetected while on operations. But they proved to be not only fierce fighters but also commanders of men. Pearl Witherington, one of these recruits, turned out to be the best shot her trainers had seen go through the course, and ended up leading a force of several thousand French resistance fighters after D-Day. But because she was a woman, she wasn’t considered to be a combatant, and she was only eligible for civilian honours at the end of the war. She returned her civilian honour and remarked that there was nothing civil about what she’d done during the war!

What was the most surprising thing you've found doing historical research for your work?

So many things! I hope my family were entertained when I would sit at the dinner table and tell them, “you’ll never believe what I found out today!!”. But probably the thing that ended up having the biggest impact on the book and surprised me the most was how important World War I is to understanding the history of women in combat roles. I was surprised because World War I is a really masculine war, and in fact it’s the most all-male war that I write about. While women were a relatively commonplace feature on 18th and 19th century battlefields (not always fighting, but often right at the front and in the thick of the action providing essential support services) by the early 20th century they’d been pushed out of European armies. So I thought that World War I would be a pretty dull period in a history of really rich examples of female fighting. But I found actually that it’s such a crucial turning point in the story. The advent of total war presented governments with a problem: they needed to have total social mobilization to win the war, but they’d done a very good job convincing their populations that women couldn’t be anywhere near the frontline (in fact the term “home front” is invented in World War I). So this meant that governments and militaries had to devise rules to keep women out of combat – and these rules persist throughout the 20th century. So World War I is a crucial turning point in the story – and, even more interesting, is what the women were actually doing! It’s true that women didn’t fight much in the war (although there are some great exceptions, including women who dressed as men and snuck into the military in Russia, and a Russian all-female military battalion, and quite a few other extraordinary women!). Women were however very significantly involved, because in almost every European state, women had organized themselves as auxiliaries long before governments realized they’d need women – and these auxiliaries became the nucleus of official women’s military service.

A question from Sarah: if you could travel back in time to visit one of the places you’ve written about (or meet one of the people) – who, when, why?? What would you talk about?

At the moment, I would chose Weimar Berlin.

The third-largest city in the world, with a population of four million, Kaiser Wilhelm’s stodgy, rather provincial capital became an international crossroads in the years after the war. Lillian Mowrer, wife of the Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Daily News and a journalist in her own right, wrote in her memoir that Weimar Berlin reminded her “of a huge railway station; it was the stopping-off place between eastern and western Europe; everyone traveling from Paris to Moscow, sooner or later, came there.”

Weimar Berlin was politically tense, bawdy, and creative: the darker counterpart of interwar Paris. With the well-earned reputation of being the most licentious city in Europe, Berlin drew an international community of artists, political dissidents, journalists, intellectuals, and members of the Lost Generation engaged in what a later generation would term “finding themselves.” It was a period of enormous, almost hyperactive, creativity. Artists of all types—in film, music, photography, the visual arts, and the many forms of theater that flourished in the city—drew energy from the prevailing sense that the social norms had been broken twice, first by the war and later by the revolution. As a result, anything seemed possible--until it all fell apart.

I’d like to think I would talk to everyone, gone everywhere, seen everything. In reality, I would probably nurse a drink in a corner.

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with scientist Richard Miller, author of The Rise and Fall of Animal Experimentation: Empathy, Science and the Future of Research, a story in which women play a surprisingly large role.

Wise Women

One of the things I enjoy most about Women’s History Month is the fact that people share interesting programs about women’s history that I would never have found on my own. Programs that I can then share with you.

One of the things I enjoy most about Women’s History Month is the fact that people share interesting programs about women’s history that I would never have found on my own. Programs that I can then share with you.

Today’s unexpected treasure is Wise Women, a sixteen-episode podcast series about women in philosophy, put on by Philosophy Talk, a radio program and series of podcasts produced by Stanford. The first season focuses on women from the fifth through the 19th centuries. I’ve heard of five of the eight women. Three are totally new to me.

The second season will focus on contemporary philosophers—I’m embarrassed to admit that not a single name comes to mind. Thought now that I think of it, I can't name any contemporary male philosophers either.

Half the episodes of the first series have dropped. I’m part way through the first episode and I’m hooked. Both the narration and the graphics are excellent.

Here’s the link: https://www.philosophytalk.org/wisewomen

****

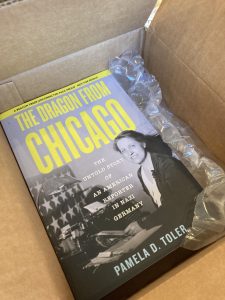

On another topic, I received galleys of The Dragon From Chicago a couple of days ago. They are gorgeous, and I am beside myself with delight, and maybe a little bit of terror, that this book is one step closer to going out into the world.

For those of you who missed it: the book releases August 6 but is available for pre-order now.