Before the GI Bill: The American Expeditionary Forces University

As far as I’m concerned one of the joys of poking about in the historical record is stumbling across tidbits that don’t make it into big picture accounts of historical events. Sometimes they don’t even make it into the smaller-scale stories that I am working on. This is one of those tidbits. It caught my imagination. I hope it catches yours, too.

In 1918, as World War I drew to a close, the YMCA and the United States Army joined forces, so to speak, to provide educational opportunities for members of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

The program had come together quickly. The YMCA began exploring the “needs and opportunities for educational work among men in the military service in connection with the American forces—not only using the war but during the period of mobilization” at the end of 1917. The Army approved the program in February, 1918. Six months later, the first stage of the program went into effect. [Rather than making a judgmental comment, I will simply suggest you insert your own experience with government or other complex bureaucracy here.]

The initial stages of the program were the military’s version of a junior year abroad. Doughboys with an academic bent and a few college credits in hand were able take classes at Oxford, Cambridge, the London Fellowship of Medicine, and the Sorbonne. Several thousand soldiers received vocational training in fourteen trades in French technical schools. (I am curious how language barriers were overcome. )

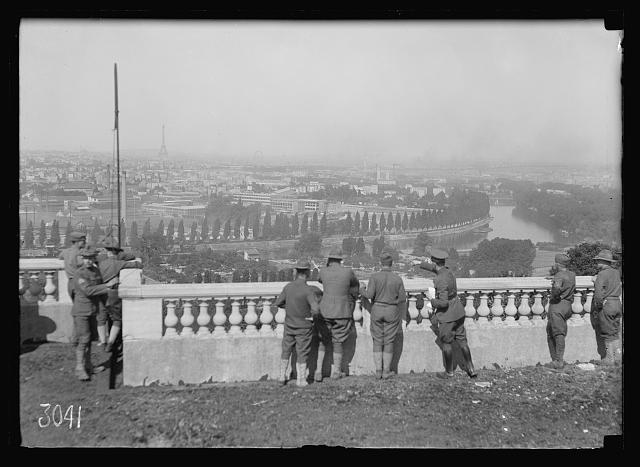

But the most ambitious element of the project was the creation of the American Expeditionary Force’s own university at Beaune, on the site of a former Red Cross hospital twenty miles south of Dijon,* and of 1,000 army post schools scattered across France and the occupied portions of Germany. The program provided a wide range of courses, 200 in all, including a full high school program, a agricultural college, a fine arts school with departments in interior design, painting, sculpture and city planning,** a medical school, and classes to prepare a few soldiers for admission to West Point. (It also had a Phi Beta Kappa chapter.)

The program was short-lived. The university opened its doors on March 17, 1919, and closed three months later thanks to the rapid demobilization of the AEF. But while it lasted, ten thousand soldiers attended the university at Beaune and more than 200,000 took classes at the post schools.

One student in the painting program told his instructor that his three months in the program “had made up for the loss of two years’ work while in the Army.” Sounds like a successful experiment in public education to me.

*The heart of the hospital was the Pavillon de Bellevue, which Isadora Duncan had used for her dance school before the war. I think it makes for a nice symmetry: from training one kind of corps to educating another.

**I have no idea why city planning was part of the arts school. And I am ashamed to admit that the thought of war-hardened soldiers who had fought in the trenches of Normandy taking classes in interior design gives me the giggles.