Back on the Great River Road: First Stop, the John Deere Historic Site

My Own True Love and I are back on the Great River Road!

For those of you who are new to the Margins: In November, 2015, My Own True Love and I set out on an adventure. We headed south for a three-week trip along the Great River Road, a conglomeration of 3000 miles of local and state roads that follow the length of the Mississippi River. We started in Memphis, went south until we reached the end of the road in Louisiana, then headed back toward Chicago, stopping at whatever took our fancy. We thought we would make it all in one trip (pause for manic laughter), but our fancy led us to make lots of stops. We only got as far as Vicksburg on the way back.

Depending on how you count, we’re starting our fourth or fifth stint on the Great River Road, beginning at the Quad Cities, and are excited to be back on the trail. As always, I’ll post stories here on the Margins about the stuff we see.*

First up, the John Deere Historic Site in Grand Detour, Illinois—aptly named in our case since we stopped there on our way to the Mississippi.

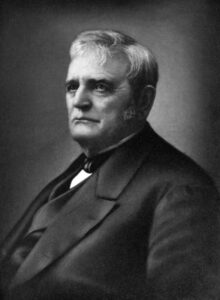

For those of you who don’t know, John Deere was the innovator who made the first commercially successful plow, one adapted to cut through prairie soil and thus critical to America’s westward expansion. **

Before Deere, most plows were made of cast iron. These were more than adequate for the light soil of the eastern United States but did not work well in the stickier soil of the prairie and could not cope with the thick roots of prairie grass. Even when a farmer could cut through the the grass, he had to stop every few yards to clean off the soil that clumped off his blade.

Deere was a Vermont blacksmith who moved west in search of opportunity. In 1836, soon after he moved to the new town of Grand Detour, Deere designed a steel blade that was “self-scouring” in response to complaints by the local farmers about the difficulty of working the prairie soil. (Repairing their broken plows made up a large part of his business.) The first year he made one of the new plows. The next year he made two. Then 40. Then 400. Ten years after he had made the first plow he was so successful that he moved the company to Moline, on the Mississippi because he needed access to better transportation—not only to ship plows out, but to ship materials in. In the early days he had to get his steel from England. (A story for another day.)

The John Deere Historic Site is located on the land where Deere lived and worked in Grand Detour. It includes the actual Deere house as it existed before the family moved to Moline, an enclosed archeological dig of his blacksmith shop with attached exhibits and a brief film, and a working blacksmith shop built to the dimensions rediscovered in the dig. Tours of the site begin whenever there are guests. (Touring the site without a guide is not an option. Tough on those of us who like to pause and think about the exhibits.) The Deere story is told with a slightly different emphasis at each of the three stops. In addition to being interested by the story, I was fascinated by the fact that the tour guides consistently “first-named” Deere and his wife—something I haven’t seen at other historical sites. It gave feeling of intimacy, as if the Deere family were their neighbors. As I suppose they were in some ways.***

The blacksmith shop was the high point of the visit, which is entirely appropriate given that the story of the Deere plow begins in his blacksmith shop. I’ve seen many blacksmiths give demonstrations of their craft/art/science but it never fails to enthrall me. There is something truly magical about the process. The blacksmith on duty during our visit to the John Deere site, named Lloyd, was one of the best I’ve seen, not simply because of his considerable skill with the metal but because of the breadth of knowledge about steel, implements, and smithing.

In short, the John Deere Historic Site is well worth a stop if you’re near Dixon, Illinois (the biggest town near Grand Detour).

*If you want to read about our earlier trips, search by Great River Road, or check in the category Road Trip Through History.

**My Own True Love is originally from South Bend, home to the Oliver Chilled Plow, which also claims to have helped “tame the prairie.” He wanted to know how the Oliver plow related to the Deere plow. The docents he asked did not know—not surprising since we were at the John Deer Historic Site, maintained by the John Deere Foundation. So I took a little dive down a very small rabbit hole once we got back to the hotel room. (And why not, I ask you?) The Oliver plow was made of chilled cast iron, using a process developed in 1869 and patented in 1873. It was cheap, durable, and well-designed to use in any type of soil. It, too was a smash hit with farmers. In fact, for a time the Oliver Chilled Plow Works was the largest plow manufacturer in the world, with the trademark “Plowmakers for the World.”

***This might not have caught my attention at another time, but I am currently struggling with the question of whether to call a historical figure by her first name. It is a fraught question, particularly when you are writing about a woman. I spent some thinking about this question in my newsletter, back in December 2020. I’m not sure I have progressed in my thinking since then.

____________________________________

Travel Tips:

1. Dixon is home to Ronald Reagan’s boyhood home, as opposed to his birthplace which is further down the road. We decided we weren’t prepared to take an hour-long tour of a house only a little bigger than the one I grew up in. You might decide differently.

2. There is another, much larger, John Deere museum in Moline, Illinois. It is well worth a visit if you’re interested in agricultural history or big machinery. (I’m not being sarcastic. We spent several hours there on a previous trip to the Quad Cities, long before I started this blog. It was fascinating.)