Shin-Kickers From History: William Wilberforce and the Abolition of the British Slave Trade

Unlike many other shin-kickers from history, William Wilberforce was a card-carrying member of the privileged classes--wealthy, educated, male, white.

Born in 1759 to a wealthy merchant family in the Yorkshire port of Hull, Wilberforce spent his teen years and early adult life in what he later described as "utter idleness and dissipation". While a student at Cambridge--where he majored in gambling, drinking, and late night parties--he began a lifelong friendship with future Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. In Pitt's company, he discovered a new source of excitement: politics. He was first elected to the House of Commons when he was only 21 and showed every sign of being nothing more than a political playboy.

His life changed five years later, when he discovered Evangelical Christianity--then a source of political and social radicalism. His first thought was to leave Parliament and enter the ministry. John Newton, best known today as the composer of "Amazing Grace", and Pitt* convinced him that he could do more good from Parliament than he could from the pulpit. Wilberforce soon found his cause: the movement to abolish the slave trade.

It was no small task. The Atlantic slave trade was an important part of the British economy, even though slavery was abolished in Britain itself in 1772. Britain made enormous profits on every step of the triangular trade: shipping textiles and other manufactured goods from Britain to Africa, slaves to the plantation owners of the West Indies and the American South, and slave-produced cotton, tobacco, and sugar cane back to Britain.

From 1787 until he retired from Parliament in 1825, Wilberforce was the public face of the abolitionist movement in England. He proposed legislation outlawing the slave trade every year for eighteen years. He was backed by petitions signed by hundreds of thousands of British subjects and opposed by the powerful shipping interest.

In 1807, Parliament passed a law abolishing the slave trade in British colonies and making it illegal to carry slaves in British ships. The practical impact of the legislation was limited. The statute did not change the legal position of those who were already enslaved. Brazil replaced Britain as the most important slave-trading nation and British slave traders continued to sail under foreign ship registrations. The efforts of the British navy to enforce the ban by patrolling the African coastline and treating all slave ships as pirates simply resulted in higher prices.**

Wilberforce and his colleagues turned their attention to the next step in their campaign: abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire.

Wilberforce was on his deathbed when the Abolition of Slavery Act finally passed on July 23, 1833. Job done, he died three days later.

*Already prime minister at the age of 26. Hanging out in history can give a person an inferiority complex.

**Economics can be a bitch.

Macaulay’s Education Minute

I often check in with My Own True Love when I'm unsure about a blog topic.* When I asked him what he knows about Thomas Babington Macaulay he said "He sounds very distinguished." I explained that Macaulay is best known as the most important writer of Whig history,** but that I think his real importance is his Education Minute. My Own True Love said, "He sounds like an obscure figure who has earned his obscurity."

At least I don't have to worry that this blog post is going to tell a story that everyone already knows.

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) was a literary lion in the mid-nineteenth century. He was one of the most popular contributors to the Edinburgh Review for more than twenty years. His Lays of Ancient Rome was a smash hit back in the days when poetry led the best-seller list.*** His five-volume History of England was marked not only by Whiggery, but by great story-telling. In 1857 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay of Rothly--the first of Britain's literary peers.

Like many writers, then and now, Macaulay needed a day job to support his writing habit so he became a lawyer. In 1834, he took the job of legal advisor to the Supreme Council of India and sailed for Calcutta, where his most significant and controversial contribution was his Education Minute.

In the 1830s, British administrators in India were butting heads over the question of education. In the early years of British rule, Englishmen in India were required to learn Indian languages, culture, and law so they could work effectively. New employees of the British East India Company hired tutors to teach them Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit as well as modern Indian vernaculars.**** The EIC supported schools where Indian languages and Muslim, Hindu, and English law were taught to Indians and Englishmen alike.

Around 1830, Evangelicalism and Utilitarianism were on the rise in England, bringing reform in their wake. Both "isms" were popular in the merchant classes that controlled the EIC, and their shared zeal for reform spilled over into the company's administration of India. A new generation of administrators in India argued in favor of a "trickle down" theory of education: instead of taking on the overwhelming task of creating elementary vernacular education for the masses***** they proposed creating a western-educated elite.

Macaulay came down heavily in favor of Western education in his controversial Minute. After acknowledging that he read neither Sanskrit nor Arabic, he then made the breathtaking declaration that " I am quite ready to take the oriental learning at the valuation of the orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia." He then went on to condemn Indian learning as "medical doctrines which would disgrace an English farrier, astronomy which would move laughter in girls at an English boarding school, history abounding with kings thirty feet high and reigns thirty thousand years long, and geography made of seas of treacle and seas of butter."

(And you are now saying to yourselves, "Not only is the man rightly obscure, but he's a racist butthead. " Bear with me a moment.)

But while Macaulay condemned the literature, he did not condemn the ability of those who wrote it. Many who supported the orientalist position on education suggested Indians were unable to learn enough English to understand western science, history etc. Macaulay argued they were wrong. He knew many "native gentlemen" who were able to discuss political and scientific issues in English with not only precision and fluency but with "a liberality and an intelligence which would do credit to any member of the Committee of Public Instruction". According to Macaulay, the goal of western education was to "form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, --a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect."

Macaulay's Education Minute was critical in the decision for western education for the elite.

But why does it matter, you ask me.

Because they succeeded. Britain educated a class of Indians who were indeed English in opinions, in morals, and in intellect--but not in rights. Indians who wanted a voice in their own government. And who finally demanded independence when they were unable to have equality.

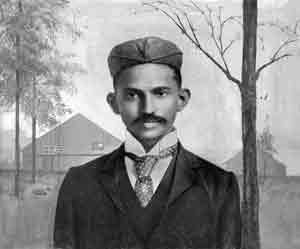

Gandhi ca. 1895

* As those of you who know me In Real Life can attest, my sense of what is common knowledge and what is not is--unreliable.

** Whig history presents the past as the inexorable progress of mankind toward constitutional government, personal liberty, and modern science. Basically, it is the opposite of nostalgia for the good ol' days.

*** The poems also had a long half-life in British schools. Children were forced to memorize them for more than a hundred years. The poems remain a permanent part of Britain's cultural landscape. One much so that one of the stanzas was quoted in a Dr. Who episode. ("The Impossible Planet." 2006). Now there's fame.

****Many also hired Indian mistresses, probably a more effective way to learn the vernacular if not classical Sanskrit.

****Just to put this in context, widespread elementary education did not become available in Britain itself until after the Reform Act of 1867, which gave the vote to most urban working men. When the vote passed, one of its strongest opponents, Robert Lowe,turned his attention to education,saying "We must now educate our masters."

Pontiac’s War

Two hundred and fifty years ago, the French and Indian Wars in North America came to an end. The Treaty of Paris redefined British, French, and Spanish colonial territories. France ceded Canada and the French territories east of the Mississippi to Britain and the Louisiana territory west of the Mississippi to Spain. Spain relinquished Florida to Great Britain in exchange for guaranteed control over Cuba. In short, France was out and Britain was in.

With the British the dominant power in North America, Native American tribes of the Great Lakes region found their world changing for the worse. The British enacted new laws making it illegal to sell weapons or gunpowder to Native Americans--a change that brought some tribes to the edge of starvation. Worse, British settlers began to expand into the rich lands west of the Appalachian mountains, clearing land for farms rather than simply building military and trading posts.

In the spring of 1763, an Ottawa chief, Pontiac, organized a multi-tribe alliance to drive the British from the Great Lakes. On May 9, following a failed attempt to take Fort Detroit using a variation on the Trojan horse*, Pontiac called for a simultaneous rising against British outposts throughout the region. By late June, Pontiac's forces had captured eight of the ten British forts west of Niagara. Two posts, Fort Pitt and Fort Detroit, remained under siege.

The commander of Fort Pitt had been warned about the uprising and was able to withstand the siege until relief forces arrived in August. ***

Unlike Fort Pitt, the siege of Detroit turned into a stalemate. The British had plenty of supplies, but were unable to break out. On Pontiac's side, anticipated French support failed to materialize, winter was approaching, and supplies were running low. On October 20, Pontiac received a letter from the French commander at Fort de Chartres (near modern St. Louis) urging him to end the siege. He withdrew his troops the next day and retreated to the west.

Pontiac continued his resistance against the British through the next year, but with diminishing support. He signed a treaty with the British in 1766.

In the short run, Pontiac's War**** succeeded. Many Great Lakes tribes formed new ties with the British similar to those they had enjoyed with the French. More importantly, British officials tried to keep colonial settlers out of Native American territories. Unfortunately, the laws the kept the settlers out of the western territories were one more irritant in the growing conflicts between Britain and its North American colonies--proving once again that you can't make everyone happy.

*Fort Michilimackinac was less vigilant, even though its commander was warned that the local tribes planned trouble. On June 2, as part of the birthday celebrations for King George III, members of the Chippewa tribe played a brisk game of baggatiway** while the 35 members of the fort's garrison watched. When one of the players threw the ball over the wall, the warriors rushed through the land gate, grabbed weapons that had been hidden under the blankets of their women as they watched the game, and attacked the soldiers. The fort was in Chippewa hands in minutes. Beware Greeks bearing gifts or people playing with balls and sticks.

** A full contact, no-holds-barred ancestor of lacrosse.

***While Captain Eccuyer waited for relief to arrive, he tried to break the siege with low-grade germ warfare. Smallpox had broken out in the fort. Everyone knew Native Americans had no stamina where disease was concern. When two of Pontiac's chiefs came to the fort to urge the British to surrender,Ecuyer gave them two blankets and a handkerchief that had belonged to smallpox victims, hoping the besiegers would catch the disease. Invasion by lacrosse looks pretty honorable by comparison.

**** It is important to emphasize that this should not be called Pontiac's Rebellion or Pontiac's Conspiracy--both of which imply that the tribes were under British rule.

(I wish I could find a less euro-centric image for this post. Any suggestions?)