From the Archives: Pippi Longstocking Goes to War

(Okay, I admit it. That's an inaccurate, click-bait of a title.)

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women's History Month hard here on the Margins.

- Astrid Lindgren, 1924

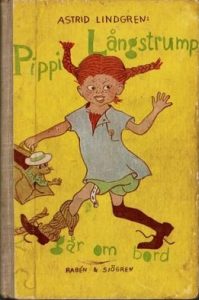

Today Astrid Lindgren is famous as the creator of Pippi Longstocking: the red-headed quirky rebel who proclaimed herself the strongest girl in the world.* In World War II, Lindgren was a 30-something housewife and aspiring author. Her war diaries, published posthumously in Sweden and recently translated into English, are a fascinating account of life in neutral Sweden during World War II.

If you read War Diaries, 1939-1945 hoping to get insight into the creative process behind Pippi Longstocking, which was published just before the end of the war. you will be disappointed. There are few references to her writing. If you want a wartime narrative written by an intelligent observer that offers a different perspective than the British accounts most familiar to American readers, Lindgren's your girl.

The diaries are a mixture of the personal and political. Marital problems, concerns about her son's difficulties at school and rumors about increased rationing are intermixed with her determination to document the course of the war. She lists the menus for birthday dinners and holiday celebrations, commenting each time on how lucky Sweden is to have abundant food and fearing that each feast will be the last. She pastes in newspaper clippings of critical events.

She also adds privileged information that adds depth to her reporting. Lindgren worked on the night shift for a government security agency responsible for censoring correspondence sent from or to other countries. Although her work was so hush-hush that her children did not know what she did, she had no hesitation about copying and commenting on sections of the letters in her diaries, including letters describing the transportation of Jews to concentration camps in Poland as early as 1941.

Lindgren's War Diaries tell the story of the war as seen through the veil of Swedish neutrality—a veil that Lindgren recognized was perilously thin. She records her relief and guilt over Sweden's relative prosperity, her shame over allowing German troops to travel through Sweden, and her fear that Russia will prove to be a greater threat to Sweden than Germany. For those of you who are serious World War II buffs, it may all be alte wurst. For me, it was a new approach to a familiar topic.**

*One of a long string of red-haired literary rebels and misfits who inspired and comforted a certain red-haired history buff as a child.

**I'm beginning to see a theme here. Sometimes I think I know nothing at all about history.

From the Archives: A Woman’s Home is Her Castle

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women's History Month hard here on the Margins.

* * *

As I believe I’ve mentioned before, in Treasure of the City of Ladies; or the Book of the Three Virtues, author, intellectual, and champion of female education Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) instructed noblewomen of her time to learn the military skills they needed to defend their property: “She ought to have the heart of a man, that is, she ought to know how to use weapons and be familiar with everything that pertains to them, so that she may be ready to command her men if the need arises. She should know how to launch an attack, or defend against one.” It was good advice. Noblewomen and queens often found themselves leading the defense of a keep, castle, or manor (and occasionally besieging someone else)—even if they didn’t have “the heart of a man.” (1) (Occasionally, not-so-noble women also found themselves under siege. Margaret Paston (1423–1484), the wife of a wealthy landowner and merchant, defended besieged properties three times against noblemen’s attempts to seize them by force.)

As I believe I’ve mentioned before, in Treasure of the City of Ladies; or the Book of the Three Virtues, author, intellectual, and champion of female education Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) instructed noblewomen of her time to learn the military skills they needed to defend their property: “She ought to have the heart of a man, that is, she ought to know how to use weapons and be familiar with everything that pertains to them, so that she may be ready to command her men if the need arises. She should know how to launch an attack, or defend against one.” It was good advice. Noblewomen and queens often found themselves leading the defense of a keep, castle, or manor (and occasionally besieging someone else)—even if they didn’t have “the heart of a man.” (1) (Occasionally, not-so-noble women also found themselves under siege. Margaret Paston (1423–1484), the wife of a wealthy landowner and merchant, defended besieged properties three times against noblemen’s attempts to seize them by force.)

The skills needed to withstand a siege were an extension of housekeeping when the idea that a man’s home was his castle was a literal description for members of the aristocracy. In medieval and early modern Europe, noblewomen were often responsible for managing family properties, and consequently for providing the military resources needed for those properties. Provisioning a household that was as much an armed fortress as a family domicile involved procuring the cannons, small arms, and gunpowder needed for its defense as well as the day-to-day supplies of food, clothing, or household linens. Noblewomen supervised men-at-arms in the course of daily life and helped mobilize the household’s resources for war. Leading its defense was one more step down a familiar road.

We find stories of women organizing the defense of a besieged castle/keep/manor in sixth century China, in the dynastic wars of medieval Europe, in the religious wars of seventeenth century England and France and in shogunate Japan. (2) Some led their men-at-arms into battle, weapons in hand. Most harangued the enemy and encouraged their troops. (Sometimes they also harangued their men-at-arms. In 1584, the wife of samurai warrior Okamura Sukie’mon armed herself with a naginata, (3) patrolled the besieged castle, and put the fear of the gods in any soldiers she found asleep while on duty.) More than one noblewoman, such as Hungarian nationalist Llona Zringyi (1644–1703) walked her ramparts at twilight in full view of the enemy, giving the besieging army a metaphorical middle finger.

For the most part, these women led the defense in the absence of their fathers/husbands/brothers/sons—who were often fighting elsewhere. In the case of Nicolaa de la Haye (ca. 1150–1230), the castle she defended was her own. De la Haye inherited the offices of castellan and sheriff of Lincoln when her father died in 1169 with no male heirs. In that role, she became involved in the conflicts surrounding the absentee King Richard the Lionhearted, his brother John, and England’s barons, that resulted in the Magna Carta. (De la Haye was on Team John.) (4) As castellan, she successfully defended Lincoln Castle twice, once in 1191 and once in 1216. Her resistance during the second siege led her enemies to describe her as a “most ingenious and evil-intentioned and vigorous old woman.” I suspect she took that as a compliment.

(1) I can’t tell you how tired I got of the many variations on “the heart of a man,” “manly courage”, “as capable as a man” while writing Women Warriors .)

(2) Japanese “castles” in the twelfth century were wooden stockades—more like a fort in the American West than a medieval European keep.

(3) A traditional weapon of samurai women, the naginata is a curved blade on a staff, similar to a glaive. Samurai women also carried a long dagger in their sleeves called a kaiken, sometimes referred to as a suicide dagger.

(4) We (and by that I mean Americans) tend to assume that John was the villain of the story because the only things we learn about him is that he was forced to sign the Magna Carta, which is seen as the documentary forefather of our own Constitution and Bill of Rights. (Not to mention his appearance as a villain in the Disney film Robin Hood.) In fact, Richard wasn’t exactly a stellar king from the British perspective. He was more interested in crusading in the Holy Lands than in ruling. During the ten years of his reign as King of England, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, (5) he spent no more than six months in England, and is reported to have said that he’d sell the place if he could find a buyer. Not a model king by any standard.

(5) Which began with him conspiring with his mother (Eleanor of Aquitaine) and the king of France to seize the throne from his father . (Not for the first time. He had previously joined two of his brothers in an unsuccessful rebellion in 1173.) Happy family.

*****

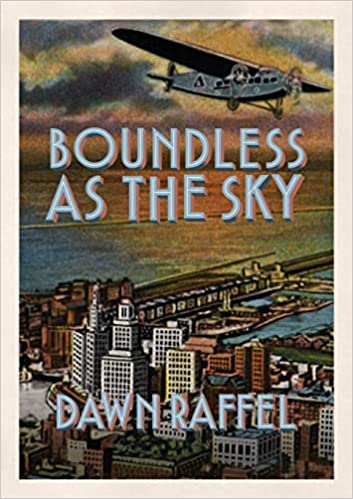

Chicago Friends: I'm going to be "in conversation" with author Dawn Raffel at the Seminary Coop Bookstore on January 26, discussing her new book Boundless as the Sky. The book is a fascinating mixture of imaginary cities, the Century of Progress world's fair (which in some ways was also an imaginary city), and Italo Balbo's dramatic landing at the fair with twenty-four seaplanes. I'm looking forward to talking to her about it. Love to see you there. Here are the details: https://events.uchicago.edu/event/189868-dawn-raffel-boundless-as-the-sky-pamela-d

From the Archives: The Other Mozart

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women's History Month hard here on the Margins.

* * *

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is impossible to avoid if you spend any time in Salzburg. A dedicated tourist could attend a Mozart concert everyday of the week without much effort. The city has transformed both his birthplace and the building where his family rented an apartment from 1773-1787 into museums. (1) At least one tour company runs a bus tour that follows “in the footsteps of Mozart.” His picture is prominently displayed in the many, many shops that sell the ubiquitous Mozartkugel (2) and his name is attached to a number of restaurants and hotels throughout the city.

I am fond of Mozart’s music, but I came away fascinated by another Mozart, his older sister Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart (1751-1829), nicknamed "Nannerl”, who was a musical prodigy in her own right.

I had been vaguely aware of Ms. Mozart before,(3) but her story clicked into focus for me in an exhibit at the Salzburg Museum devoted to historical musical instruments. The exhibit is fascinating. Instruments from the museum’s extensive collection are not only displayed and placed in context, but recordings allow you to hear them played by professional musicians. Some are familiar, like lutes, harpsichords and French horns. Others are not: the theorbo and the pommel for instance. Personally I was fascinated by the pochette,(4) also known as the dance-master’s violin, and the steel piano, also known as steel laughter.

One of the first pieces in the exhibit was Ms. Mozart’s clavichord, and a brief description of her life. She was five years older than her famous brother, and had already proven herself a talented musician at the time that he wrote his first composition. In fact, the two toured together for three years when they were children. She sometimes received top billing and a review from that period praised her in terms not that different from those showered on her younger brother: "Imagine an eleven-year-old girl, performing the most difficult sonatas and concertos of the greatest composers, on the harpsichord or fortepiano, with precision, with incredible lightness, with impeccable taste. It was a source of wonder to many."

But actions that were acceptable for a little girl were not acceptable for a grown woman. When Ms. Mozart was eighteen, her days on the concert trail were over. She was left behind in Salzburg when her father took her brother back on the road. She eventually married an older man chosen by her father, Johann Baptist Berchtold zu Sonnenburg. After his death, she returned to Salzburg, where she taught music.

There is evidence that she composed in addition to playing. Surviving letters (5) suggest that her brother consulted with her about musical issues. But unless new material comes to light, we’ll never know what her compositions sounded like because none of them have survived. *sigh*

(1) We visited the so-called Mozart Residence. I wouldn’t recommend it unless you are a Mozart groupie. There really isn’t much to see: the fact that one of the eight rooms is devoted to the musical career of his son who, by the museum’s own account, wasn’t anything special as a musician or composer tells you all you need to know. Much of the audio tour is snippets of Mozart’s music, which is pleasant but there are plenty of places to hear Mozart while you are in Salzburg. The best part of the museum was the final room, which talked about the use of Mozart’s image as a marketing device and included a life-size cardboard silhouette of the composer. At 5 foot and almost 2 inches, I would have towered over him.

(2) The candy—a ball of pistachio marzipan coated with a layer of nougat covered with a layer of chocolate—was created by a Salzburg confectioner in 1890. It seemed like a must try for a Salzburg visit. My take? *Meh* (Of course, I felt the same way about the Sacher torte we ordered at the Sacher hotel. I may not be the right audience for Austrian sweets.)

(3) Somehow calling her “Nannerl”, as so many scholars do, feels disrespectful and simply calling her Mozart will lead to confusion.

(4) French for pocket, because the instrument was theoretically designed to fit in a pocket. Though not in any pocket I’ve ever had.

(5) Of which there are many, thanks to Ms. Mozart herself, who served as the family’s unofficial archivist