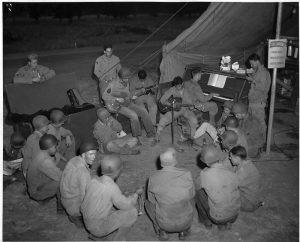

Pianos for Victory

This story has been brought to my attention twice in the last 48 hours from two different sources.* Sometimes the universe says “You need to write a blog post about this!” in a very clear voice.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, raw materials of all sorts were diverted to the war effort and manufacturers retooled their plants to produce war material. (Typewriters were an interesting example of this.)

At first, the Steinway piano company used its capacity for making big wooden boxes to manufacture tails and wings for gliders for troop transport and coffins for bringing casualties home. Late in 1941, the company received a request from the War Production Board to design a small upright piano that could be made inexpensively and shipped in a crate to soldiers in the field. The first prototypes were ready by June, 1942.

The pianos were designed to stand up to wartime conditions, without access to the materials the company would normally use. They didn’t have front legs because legs might have broken off when airdropped. They used only one-tenth the metal of a regular Steinway. (Just because the government ordered the pianos didn’t mean Steinway had access to the metals they used to make pianos in peacetime.) They had celluloid keys instead of ivory. The wood was treated with insect repellent and the glue was water resistant.

Known as “Victory Vertical” pianos and “G.I. Steinways,” the pianos were 40-inches tall and weighed 455 pounds. They were made with handles under the keybed and in the back, making it easy for four soldiers to carry them. They were shipped, and sometimes airdropped onto the battlefield, with a set of tuning tools, instructions for using them, spare parts, and sheet music, including current popular music for sing-alongs, Protestant hymns, and boogie-woogie tunes.

The first shipment of 405 olive drab pianos were greeted with enthusiasm, and were quickly followed by more. Later pianos were painted in olive drab, blue, or gray depending on the service to which they were shipped.

The Steinway company shipped more than 3,000 Victory Vertical pianos between 1943 and 1953, when production ended. The last of the pianos went into service in 1961, when the captain of the newly built nuclear submarine USS Thomas A. Edison requested that one be installed in the crew’s mess area. It remained on board until the sub was decommissioned in 1983 and is now on display in the Navy Historical Center in Washington, D.C.

*With thanks. Keep those stories coming, y’all.

From the Archives – Shin-kickers from History: Joan of Arc

Several months ago, I asked a group of family and friends to tell me what they knew about Joan of Arc, aka St. Joan, aka the Maid of Orleans--no stopping to look up the details. I needed to know how familiar the average smart, well-read, non-specialist is with her story.* The accuracy and detail of the answers varied, though everyone knew she was French and no one said “Joan who?” ** As I read the answers, one thing stood out: the people who remembered the most were all women who had been fascinated by her story at that age, somewhere between 9 and death, when smart girls look for historical role models to tell them that it’s okay to be tough/mouthy/opinionated/different.***

I was one of those girls. I’m still fascinated by Joan, and other warrior women. And I was delighted when two new biographies of the Maid of Orleans landed on my book shelves in recent months.

In Joan of Arc, historian Helen Castor returns to the subject of powerful medieval women that she explored so successfully in She Wolves. Castor brings a new twist to a familiar story, signaled in the use of "a history" rather than "a biography" as a sub-title. Instead of starting with Joan, she begins with the turbulent history of fifteenth century France, placing Joan's achievements within the context of the bloody civil war that began with the assassination of Louis, Duke of Orleans, at the instigation of his brother, the Duke of Burgundy, in 1407. ****

Castor takes the reader step-by-step through the labyrinthine story of a France divided between Burgundians, the supporters of the French royal family, and the opportunistic claims of England's Henry V to the French crown. Joan appears in the narrative one-third of the way through the book, when all hope of the French dauphin claiming his throne seems lost. Even after she appears, Castor never loses sight of the larger picture, placing Joan's story within the context of previous French visionaries, politics within the French and English courts, and the realities of fifteenth century warfare.

Written with both scholarly rigor and the narrative tension of a historical thriller, Castor's Joan of Arc makes the story of St. Joan more understandable, more complex, and more extraordinary. Or as cultural historian and mythographer Marina Warner put in in her own study of St. Joan: “so grand, so odd, so stirring.”

One of these days I’ll get to Kathryn Harrison’s Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured. Then it will be time for compare and contrast.

* Note to self, next time you have this kind of question, post it on the blog. *Headsmack*

**My favorite answer captured the essence of the legend without reference to historical detail: “She was that sturdy girl that wore armor, carried a sword, fought the bad guys, stormed their castles, was burned at the stake for her troubles, and smiled while burning...thus Sainthood. ???????????”

***I’d love to think that modern pre-teens didn’t need these role models the same way we did in the Dark Ages before the women’s movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but I’m afraid it’s not true. Hence the popularity of the A Mighty Girl website and the #LikeAGirl campaign.

****That assassination was the subject of another book I loved, Eric Jager’s Blood Royal. Read together, the two books illuminate not only the period, but each other. It’s thrilling when that happens.

Talkies, or “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet”

Recently I’ve been dipping into the early days of talking pictures. As usual, a very specific question led me down unexpected rabbit holes. For once, I wasn’t surprised by the depth of my ignorance. Everything I knew about the first “talkies” came from the film Singin' in the Rain—a movie that I love but that I assumed was not a good historical source.*

Here are some bits that caught my imagination:

- The Jazz Singer (1927), which in the shorthand version of film history is considered the first commercial talking picture, in fact used elements of both silent and talking pictures. Recorded using “sound on disc” technology, the sections of the film that included sound were relatively short, and were mostly devoted to Al Jolson singing—an obvious intermediate step between phonograph records and silent movies. The recordings also caught several improvised comments by Jolson, which the director chose to keep in the final soundtrack and which generated much of the excitement about the film. In my opinion, one of those lines sums up the place of The Jazz Singer in film history: “You ain’t heard nothing yet!” I can’t help but wonder if Jolson wasn’t thinking of the process of making films when he said it.

- Singin' in the Rain used one piece of “talkie” history to great affect, revealing one of early Hollywood’s technical secrets in the process. To my surprise, the use of aspiring actress Kathy Seldon (Debbie Reynolds) to dub the lines for silent film Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen) because Lamont’s voice was, let’s just say unpleasant,** reflected a real technique used when silent film actors attempted to make the leap to sound. The technique was used not only to cover for voices that were too shrill, too nasal, too soft or just, “too,” but also to hide strong European accents. Only two years after The Jazz Singer, Alfred Hitchcock used the technique effectively in Blackmail (1929), in which actress Joan Barry dubbed lines for Czech Anny Ondra, whose accent was considered unacceptable for English-speaking audiences.***

- Introducing sound into movies using the first viable “sound-on-disc” and “sound-on-film” technologies**** forced movie makers to find a way to mask unwanted sounds. Ironically, the biggest problem was the sound of the cameras themselves. At first cameras were isolated in heavy sound-proof cabinets, sometimes called “iceboxes,” to mute the sound of their motors, which limited directors’ ability to move their cameras. I don’t remember seeing such a thing in the on-set scenes in Singing in the Rain. Perhaps it’s time to watch it again?

*Though in fact, Singin' in the Rain came out only 25 years after The Jazz Singer, something I hadn’t realized until I went down this particular rabbit hole. The film’s creators may have known more about movie history than I gave them credit for.

**In an interesting twist, Hagen “dubbed” her own spoken lines. .

***This surviving clip of a sound test with Hemingway makes it clear that her accent was, in fact, quite light. (It also makes clear that Hitchcock was a bit of a jerk.)

****Sound-on-film ultimately won, but for a time movies were produced in both formats to accommodate the fact that theaters had different set-ups. During this period, some studios also produced parallel silent versions of films because smaller theaters were slow to catch up.