In which I introduce novelist Greer Macallister and an interview series for Women’s History Month.

Last year historical novelist Greer Macallister ran a wonderful series on her blog for Women’s History Month titled #WomensHistoryReads. The concept was simple: she asked historians and historical novelists to answer three questions regarding writing and reading about women in history and asked each of us to ask her a question in return. I eagerly awaited each post as it came out. If you want to read them, this index gives you access to all of them: http://bit.ly/2NBhG3f

She’s running the series again this month, talking only to novelists. With her blessing, I’m borrowing (okay, stealing) her format for a similar series here on the Margins. Over the next month, Monday through Thursday, some of my favorite people involved in women’s history will answer three questions about the work they do and how and why they do it. I’ll chime in on Fridays.

The obvious person to start with is Greer Macallister herself. I know Greer from the days when we both hung out in a wonderful on-line writing group called Backspace. I love her books. I’m eagerly awaiting the next one, which comes out any day now. Here’s her official bio:

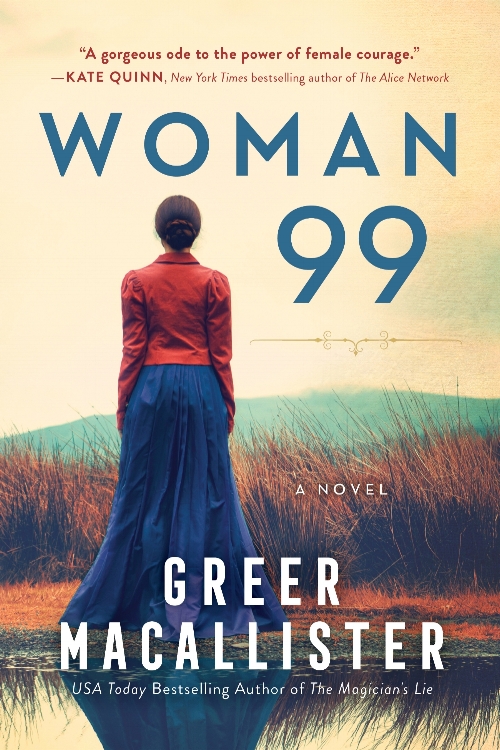

Raised in the Midwest, Greer Macallister is a novelist, poet, short story writer, and playwright who earned her MFA in creative writing from American University. Her debut novel, The Magician’s Lie, was a USA Today bestseller, an Indie Next pick, and a Target Book Club selection. It has been optioned for film by Jessica Chastain’s Freckle Films. Her novel Girl in Disguise, also an Indie Next pick, received a starred review from Publishers Weekly, which called it “a well-told, superb story.” Her new novel, Woman 99, is forthcoming from Sourcebooks in March 2019. A regular contributor to Writer Unboxed and the Chicago Review of Books, she lives with her family in Washington, DC.

Take it away, Greer:

Tell us about a woman from the past who has inspired your writing.

The first kernel of my new novel Woman 99 was the inspiring life of Nellie Bly, whose intrepid reporting adventures took her many places, including literally around the world. One of her most striking assignments involved feigning madness to investigate and expose the harsh conditions at the notorious Blackwell’s Asylum in New York City, which she did in 1887. In “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” she wrote, “The insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island is a human rat-trap. It is easy to get in, but once there it is impossible to get out.” I took that as the jumping-off point for a story about a young woman who uses some of Nellie’s methods to get into an insane asylum, but for a different reason: to rescue her beloved sister. I chose not to write about Nellie herself since there are plenty of great non-fiction accounts already in existence–after all, she was a reporter! Most of what she did was very well-documented.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important?

I think it’s a shame that we have to have it but I’m glad we do, if that makes sense. It would be great if women’s stories from history were considered as important as men’s, that high school history textbooks made the names Kate Warne, Irena Sendler and Ida B. Wells as familiar as John Wilkes Booth, Oskar Schindler and W.E.B. DuBois. But until that happens, having an annual reminder to pay attention to these stories, to seek them out? I think it’s great. It’s no excuse not to call attention to great books by and/or about women the rest of the year, but it’s an excellent occasion to dig deeper and shout louder.

What’s your next book about and when is it coming out?

Woman 99 hits shelves on March 5, 2019, and I couldn’t be more excited! It’s about a young woman whose quest to free her sister from an infamous insane asylum risks her sanity, her safety and her life. I describe it in a lot of different ways, but this is probably my favorite: it’s kind of a 19th-century Orange is the New Black, following a group of women on the fringes of society who find connection and community in the last place you’d think to look. I’m also fond of the way Publishers Weekly summed it up in their review: “Macallister sensitively and adroitly portrays mental illness in an era when it was just beginning to be understood, while weaving a riveting tale of loyalty, love, and sacrifice.”

A question for Pamela: As you researched Women Warriors (which I am so excited to read!), were you able to get a sense of why women’s stories so often faded from the historical record? I imagine in some cases the elimination or manipulation of women warriors’ stories was malicious, but in others, purely a function of who was responsible for writing history down.

There are a lot of different reasons why individual women’s stories have been pushed into the historical shadows and buried in the footnotes. But once you get past the particulars, there are two stages in the historical process that filter women out of the story—as well as the poor and the minority groups of any given time and place. (It’s important to remind ourselves that for much of history western Europe was culturally backward, that Christianity was originally a minority sect that was looked on with suspicion by rulers as late as the twelfth century, etc. In short, the face of the dominant power changes over history, though it is usually male.)

In the first stage, someone decides what is important to record and preserve—a decision that often leaves women out of the story, or the burial cairn, or the inscription, or the archive. Sometimes women’s stories make it into a historical footnote or an archival collection because they are attached to those of important men. Sometimes they are told as a good example or a horrible warning. Sometimes they are left out of the official history for political reasons or because their presence detracts from the official narrative. And when they do appear in the historical record, their stories, like all historical evidence, are filtered through the assumptions of the (almost always) men who wrote them. Character assassination, salacious speculation, and hagiography are all common.

In the second stage, later historians often filter women out of the story because their (or should I say our?) presence doesn’t fit our shared cultural narrative about what’s important and who does important things. As a result, historians have often not looked at events through the lens of women’s lives and at the same time have not looked at examples of women involved in typically male spheres. And sometimes they have worked really hard to explain why the evidence that a particular woman was involved was wrong. It has been a “lose, lose and, yes, you lose again” game.

That began to change around 1980, with the rise of women’s history. But we have a long way to go.

Want to know more about Greer Macallister and her novels?

Check out her website: www.greermacallister.com

Follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter

Check in on Monday for the next Telling Women’s History interview: Next up, Heath Lee, author of the The League of Wives.