Telling Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Elizabeth DeWolfe

I interact with Elizabeth De Wolfe almost everyday. We are both part of a top-secret revolving Facebook writing challenge group, which provides friendship, support and an occasional kick in the butt as needed. Elizabeth regularly proves herself to be witty, wise, and passionate about the work.

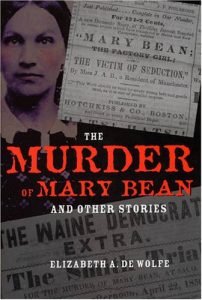

She is is Professor of History and co-founder of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at the University of New England (Biddeford, Maine). She teaches courses in American women’s history, world history, and American culture. Elizabeth is the author of several books and articles, including the award-winning books Shaking the Faith: Women, Family, and Mary Marshall Dyer’s Anti-Shaker Campaign, 1815-1867 (Palgrave Macmillan 2002) and The Murder of Mary Bean and Other Stories (Kent State 2007). She earned her Ph.D. in American and New England Studies at Boston University. De Wolfe makes her home in southern Maine with her husband, a rare books dealer, and Bella, a fat cat.She also plays in a ukulele band—a fact that warms my heart.

Obviously the perfect person to participate in Three Questions and an Answer. Take it away, Elizabeth!

Even well known women in the nineteenth century are often neglected by biographers and historians. What led you to write about “ordinary” nineteenth century women?

Boredom, assumptions, and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. The boredom comes from my 1970s high school history class—long lists of names and dates of great white men and the battles they fought, the treaties they signed, the elections they won, and the inventions they made. I wondered if people like me – female, not destined to be famous—ever “did” anything in history. History, as I understood it at that young age, was something famous people did. Years later, much to my surprise as my teenage self imagined a career as a scientist, I undertook my PhD in American and New England Studies. While hunting for a dissertation topic, my husband, a rare books dealer and expert in Shaker history, suggested I look at the anti-Shaker activist Mary Marshall Dyer. The conventional wisdom was that she was a hysterical woman, a one-time Shaker who had left the sect while her children and husband remained; that she was a bit unbalanced to keep up a 50-year campaign against such an ostensibly benign group in pursuit of the return of her children. But as I read her own works, I saw that that assumption – a view of Shaker history colored by nostalgia – was way off the mark. She wasn’t unstable; she was angry for the loss of her children, frustrated by her social and legal invisibility, and hamstrung trying to speak out for what she called “the just rights of women” in an era when speaking out was a sign of, well, instability. By putting aside assumptions and approaching her work with a blank slate, I saw her life in a new, revelatory light. And it was right around this time that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich received the Pulitzer Prize for A Midwife’s Tale. What captured my interest was her meticulous method of close reading, of tracing out relationships, of going back even further in time to understand her subject’s present. This research method showed me how I could troll the archives to uncover the stories of ordinary women who had been mischaracterized or simply overlooked–people like me.

You teach a variety of women’s history courses. What aspects of women’s history surprise your students most? What outrages them?

Students are surprised that there is a history. The first hurdle is to get them past the mindset that history is just the “important” things, and by important the default is largely “done by men.” The second hurdle is to get beyond the Queens and scatterlings of female authors or inventors who get a compensatory note in the historical record. Then we drill down to the everyday. Students are angry that they didn’t know there was a history and that women have largely been left out of what history there is. They are outraged that not all that much has changed globally and that we see similar themes and dynamics at work across cultures and time. This fury often spurs them to take action, which makes me both proud of them and hopeful for the future. What I want is for my students to come out of my classes asking questions: to use their voices, to ask what has been women’s role in a given place or time or situation. What was roles have women played then, what roles do women play now, and what dynamics make that so? As they move beyond college into their lives, if they raise their voices and ask questions, I am a happy teacher.

What have you read lately that you loved?

I loved Jill Lepore’s Book of Days, an exploration of the journal kept by Jane Franklin, sister of Benjamin. I found it so evocative that Franklin’s roughly made, private record not only survived but within its simple entries unleashes a window into her world. Lepore illustrated the richness of Jane Franklin’s own life for its own sake, well beyond being the sister to a founding father. Caroline Fraser’s Prairie Fires on the life of Laura Ingalls Wilder was mind-blowing. It’s hard to get the image of Melissa Gilbert’s TV character out of your head when thinking of the Wilders, but this work will do just that. In some ways she blows apart an American icon, but reveals a much richer story. Emily Wilson’s new translation of The Odyssey is the very opposite of the dusty, staid edition we suffered through in college. And I was captivated by Michelle Obama’s Becoming.

Question for Pamela: What is one thing in women’s history or women’s contemporary lives that you would like to see accomplished before your years are done?

There are so many ways to answer that question, but I’m going to go with the answer that first comes to mind, even though it has nothing to do with women’s history. I’d like us to reach the point where no woman is asked “Do you work or are you a stay-at-home mother?” It may seem small compared to equal wages or inclusion, but the assumption that being a mother is not work is the base for a wide range of beliefs about the value of women’s work.

Want to know more about Elizabeth De Wolfe and her work?

Check out her website: www.elizabethdewolfe.com and her Facebook page: Elizabeth De Wolfe, Author

Follower her on Twitter: @Prof_edewolfe

Come back tomorrow for another Telling Women’s History Interview. I’ve got an entire month of some of my favorite history people talking about the work they do and how they do it. Next up: Vanya Eftimova Bellinger, author of Marie von Clausewitz: The Woman Behind the Making of On War

I’d never heard of Mary Marshall Dyer. Was her campaign ever successful? I can’t imagine being separated from loved ones for 50 years. That must have been incredibly hard.

Yes and no. She succeeded in making an independent life for herself which began in 1830 after successfully (first) changing New Hampshire divorce law and (second) then divorcing her husband-turned-Shaker. The divorce restored Mary to legal and social visibility — that is, she could act as a feme sole — earn wages, contract debts, buy and sell property. When she died she owned property and assets. Yet, she never did retrieve any of her children. As each reached adulthood, they all chose to remain with the Shakers. Four of five died in the faith (including her son, Caleb, who was shot and killed in 1863 by a Civil War veteran attempting to retrieve his Shaker-held children). The fifth child left the faith in the 1850s as an adult, married, and then (sadly for Mary) moved to Wisconsin. Dyer died alone in her home in 1867.

Thank you for the answer. How interesting.