Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Eve M. Kahn

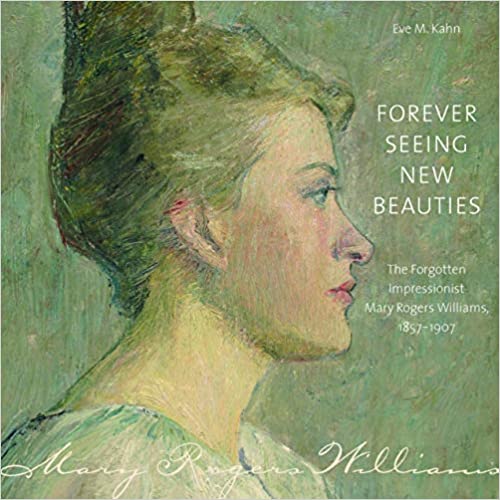

Independent scholar Eve M. Kahn is the former Antiques columnist for The New York Times. Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907 (Wesleyan University Press, 2019) won prizes from organizations including the Connecticut League of History Organizations and the Connecticut Center for the Book. Kahn contributes regularly to the Times, The Magazine Antiques, Apollo magazine and Atlas Obscura. Her book in progress is provisionally titled Queen of Bohemia Predicts Own Death: The Forgotten Journalist Zoe Anderson Norris, 1860-1914.

Take it away, Eve!

Q: Writing about a historical figure like Mary Rogers Williams requires living with them over a period of years. What was it like to have her as your constant companion?

A: One of the funniest moments came right after the book was published—when I first had it hand, with Mary’s luminous painting on the cover and the wonderful heft of the high-quality paper. I vividly dreamed that I was having lunch with Mary. It was just the two of us, outdoors, on some kind of restaurant terrace in Italy, overlooking a flowered hillside. I handed her the book and, blushing a little, told her that I hoped she’d like it. Then I felt my face drain of color: oh no, it tells her she’s going to die young. I started to apologize, stammering, almost rising up in my seat. But she took it all in stride: “Oh, don’t worry; knowing that helped me get a lot done in the short time I had.” Of course it makes no sense—how would my book published 112 years after her death have forewarned her? But I grew to care so much about her feelings, while living amid and poring over her handwritten letters for so many years. And I’ve also had nightmares, while traveling, that some part of her archive has gone missing—I wake up jetlaggedly convinced a sketchbook is gone, a box has been accidentally thrown out. Her papers, just to be clear, are well stewarded. They’re in neat chronological order, boxed on shelves in my bedroom, they’ve been transcribed in backed-up files, and they’re a promised gift to Smith College.

Q: One of the questions I’m fascinated with right now is how biographers name their subjects, particularly when writing about a woman. Did you choose to use Mary or Williams (or something else) in your book, and why?

A: I call her Mary. I alerted readers, however, that her family called her Polly, although I have never dared call her that even after a decade in her company. Even to her closest friends she was Mary or Miss Mary. Polly only appears in my quotes from her family letters, which sometimes give such an intimate look at how a baker’s daughter felt far from home. At one point Mary wrote to her sisters from Paris that she was mastering French: “Si vous pouvez voir votre soeur Polly, la prosaique dans la belle Paris, what would you say?” And “Polly” appears in her sisters’ funny quotes from their travels with her. Mary often longed to wear men’s clothing, especially military uniforms, and during one of her trips, her sister Laura tattled in a letter home: “Polly is again struck by the stunning appearance of the German officers.” For my book’s whole large cast of characters, to make them as vivid as possible to modern readers, I mostly used the first names of people in Mary’s inner circle and sometimes nicknames. Her baby-faced architect friend Alfred Gumaer was known as Gummy. The college professor and administrator Marie Elizabeth Josephine Czarnomska, the imperious daughter of a Polish aristocrat, was nicknamed “the Czar” and sometimes “Czarina.” I’ve tried to capture how much of Mary’s inner life, the casual expressions of her observations and affections, are documented in letters scrawled at a fast pace.

Q: You describe Williams as “the Mary Cassatt you’ve never heard of”. Why was her story and her art forgotten, and what can that tell us about how women artists are erased from history?

A: A Gilded Age woman artist could far more easily make a name for herself if, like Mary Cassatt, she had family money, no need for a day job, a network of wealthy patrons, and a long life with time to try to get her paintings in the hands of institutions and prominent collectors. The more productive a woman artist had time and resources to be, the more she could exhibit, the more reviews appeared in her lifetime, the more of her works survive, the more collectors, curators and dealers now know of her, the higher the prices—it all snowballs. It accounts for the fact that today, Mary Cassatt is one of few women artists people outside the art world can name, along with Georgia O’Keeffe and Frida Kahlo. And there was subtle and unsubtle entrenched misogyny everywhere in the art world that “my” Mary writes about: sneering male critics, exhibitions that women could only attend on “ladies’ days,” male art dealers who publicly praised but privately mocked mediocre paintings by famous men—Mary quotes some great gossip she heard at New York galleries. Mary’s letters also reveal the small dreary demands that reduced women’s productivity. She describes hours spent waxing her floors and getting custom clothes made—ready-to-wear didn’t exist in her day. And after her sudden death, her surviving sisters, one of them a retired teacher and the other a homemaker, with no expertise in maneuvering in the art world, could not do much more for Mary’s legacy than to make sure her letters and paintings were safe and dry. Which is how they were, slumbering away in the hands of a Williams family friend’s descendants, when I stumbled upon them in a funny way in 2012.

Question for Pamela: My current biography subject, the writer and reformer Zoe Anderson Norris (1860-1914), heroically documented desperate immigrant poverty on the Lower East Side. But she also said about a dozen prejudiced things that I for one wish she hadn’t—and which, had she lived longer, she might have regretted as times changed around her and not wanted in her biography. How do you deal with some really unfortunate words or actions in the life of a deeply interesting person you admire enough to write about? How do you ask for some kind of forgiveness and perspective from the reader, without downplaying the missteps too much, what’s the right balance?

I think novelist Hilary Mantel said it best in a talk she gave to the Royal Society of Literature in 2010: ”Learn to tolerate strange worldviews. Don’t pervert the values of the past. Women in former eras were downtrodden and frequently assented to it. Generally speaking, our ancestors were not tolerant, liberal or democratic. Your characters probably did not read The Guardian, and very likely believed in hellfire, beating children and hanging malefactors. Can you live with that?”

As a biographer or a history, I think the most useful thing we can do is state clearly that our subjects held ideas that are troubling from a modern perspective, and often stated them in ways that we find offensive. And then to place those ideas within their historical context—not in an attempt to excuse them, or downplay them, but to explain them.

* * *

Want to know more about Eve Kahn and her work?

Check out her website: Evekahn.com

Read this interview in Vogue: American Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams Is Finally Getting the Recognition She Deserves

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with author and musician Kathryn Atwood, who writes collective biographies about women in war for younger readers.