Talking Abut Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Stephanie Gorton

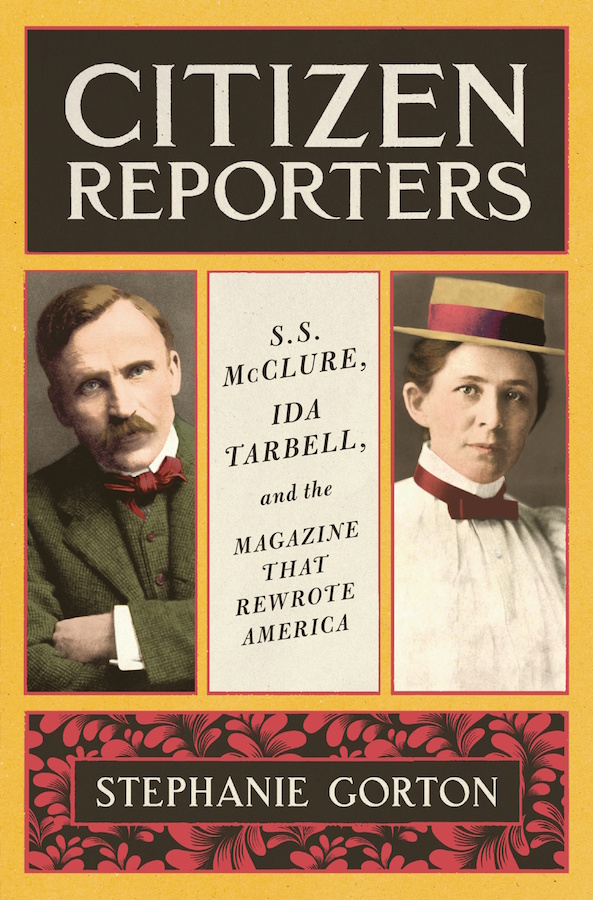

Stephanie Gorton wrote Citizen Reporters: S. S. McClure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine that Rewrote America (2020), a finalist for the Sperber Prize for journalism biography. She has written for The New Yorker online, Smithsonian online, The Paris Review Daily, and LA Review of Books, among other publications, and been featured on radio shows including On Point. Previously, she held editorial roles at Canongate Books, The Overlook Press, and Open Road. She was a fellow with the Logan Nonfiction Program at the Carey Institute for Global Good in 2021. Gorton lives in Providence, Rhode Island, with her family.

Those of you you are regulars here on the Margins know that I am all about historical women journalists these days, which means I’ve had Citizen Reporters on my radar ( and my TBR pile) ever since it came out. I was thrilled to have a chance to learn more about the book.

Take it away, Stephanie!

What path led you to Ida Tarbell? And why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

I didn’t set out to focus on Ida Tarbell; she’s been the subject of some great biographies already. Originally, I wanted to write a history without a traditional main character, a kind of survey of the muckraking journalists in the McClure’s Magazine group and the stories they told. But the research entailed was overwhelming, and with a half-dozen subjects who had different trajectories and timelines, the narrative fell flat! After six years of research, I took the difficult step of putting the whole draft away for a few months. When I finally looked at it again, what immediately stood out was that I had unwittingly gotten wrapped up in Tarbell’s story and especially in the collaborative, sometimes exploitative relationship she had with her editor, S. S. McClure.

Tarbell’s work and legacy are worth getting to know today for several reasons. When it comes to the craft of journalism, Tarbell’s self-imposed ethics have become standard: confirming sources’ reports with a separate source wherever possible, for instance. Her History of the Standard Oil Company still stands as one of the most influential works of twentieth-century journalism, alongside the reporting of people like Rachel Carson, John Hersey, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, and Edward R. Murrow. The Standard Oil series alone had such an impact on public opinion it has been credited with driving the 1911 Supreme Court decision dissolving the Standard Oil monopoly. But it’s not only deeply worthy; it’s a page-turner. The language is fresh, and the facts unfold according to a sensibility that’s clearly familiar with drama, with the dynamics of great fiction, I even often thought of TV documentary series and the elements that keep you hooked through a long series. Tarbell’s memoir mentions how she used to hide away in her parents’ house with a slice of lemon cake and read Dickens, George Eliot, Thackeray, Wilkie Collins, and there are absolutely in her articles an almost novelistic cast of noble characters and enterprises, shadowy schemes, and a kind of vivid, small-grain level of detail that’s hard to put down once you start reading.

Apart from her genre-defining writing and its transformative impact on antitrust history—a history that is certainly relevant now, when our lives are tracked by Amazon, Facebook, and other monopolistic behemoths every day—Tarbell was a remarkable person. She shunned fame, navigated a workplace that demanded all emotional and intellectual resources, and was kind of a bad feminist in that she never supported women’s suffrage. I think there’s a lot of insight to be gained in exploring complexities like that, in addition to the aspect of her character most intriguing to me: she held herself to a standard of meticulousness that never relented and required severe compromises in her personal life.

Ida Tarbell was well-known in her day, but today often appears as a secondary character in histories of her period. Why do we tend to forget, or at least minimize, the roles women play in history?

History textbooks have a lot to answer for. Thinking of how I first studied American history, going from one presidential administration to the next, many figures and cultural shifts were relegated to colorful context. That framework tends to stay with us through adulthood: so many works of narrative history dive deep into the lives of authority figures, or recount wars, or look at a particular piece of legislation. Marginalized groups don’t get to be part of the “real” story. For a long time, women were largely excluded from the realm of politics, at least on paper, so their achievements tended to be sidebar material: women’s history, not American history. I’m always catching ways in which I’ve been formed by this thinking myself.

Consequently, what I’ve frequently heard is that Ida Tarbell and Ida B. Wells are the same figure in people’s minds: two reporters of the same name in the same era, doing investigative work, but with a huge difference–Wells was risking her life because she was black and investigating lynching. Similarly, many people know the term “muckraking,” but sometimes use it interchangeably with Yellow Journalism – the two are very different, and how you value one shouldn’t color how you view the other! The press had a transformative role during the Gilded Age and that era has many parallels to today, so I wanted to give it center stage.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a narrative history of the birth control movement, focused on activists Mary Ware Dennett and Margaret Sanger, tentatively titled The Icon and the Idealist. The book will track their campaigns to legalize birth control against what was happening culturally from the 1910s to the 1930s—urbanization, modernist literature, silent film, the 1913 Armory show, for example.

Dennett is a fascinating figure, though her belief that birth control should not be subject to gatekeeping by physicians—that access to contraception was a free-speech issue, not a doctor’s-privilege issue—did not end up succeeding. She’s the “idealist” of the title. Sanger’s name is more familiar to us today, but what’s less known is that many of her arguments and achievements can be traced to her contest with Dennett. Their contrasting visions and strategies have much to teach us today, both about how we as a society have adjusted to the idea of women’s bodily autonomy and the risky, happenstance ways in which grassroots activism sometimes leads to legislative change.

A question for Pamela: Who’s more challenging to write for, children or adults?

From my perspective, children are definitely harder to write for, though I think that says as much about me as it does about children and children’s books. Even when I’m writing for adults I don’t always have a clear grasp about what I can expect people to know.* That problem is even worse when I’m writing for kids. (To be honest, even when I was a kid I didn’t know what I could expect other kids to know.) In my last book for kids, Across the Minefields, I was surprised when my editor asked me to add a sentence or two explaining World War II early in the book.

Also, even though I am good at making complex ideas understandable, my default style is complex sentences. This does not work for the 8-12 year old set. Which means I write a draft as simply as I can. Then I go back and break down sentences into their constituent parts—and take out any phrases like “constituent parts” that slipped in when I wasn’t looking.

It is a challenging and profoundly satisfying process.

*Luckily I can always call on My Own True Love and my BFF from graduate school for a reality check. I regularly have conversations with both of them that start with “Is this something everyone knows?” It is amazing to me how often the answer is know—er, no. (A Freudian typo if there ever was one.)

***

Want to know more about Stephanie Gorton and her work?

Check out her website: stephaniegorton.com

Follow her on Twitter: @sdgortonwords

* * *

Come back tomorrow for a whole bunch of questions and an answer with author and art historian Bridget Quinn, whose latest book was described by NPR’s Susan Stamberg as “spunky attitudinal, SMART writing,” (Now that’s praise worth having!)