Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Marcia Biederman

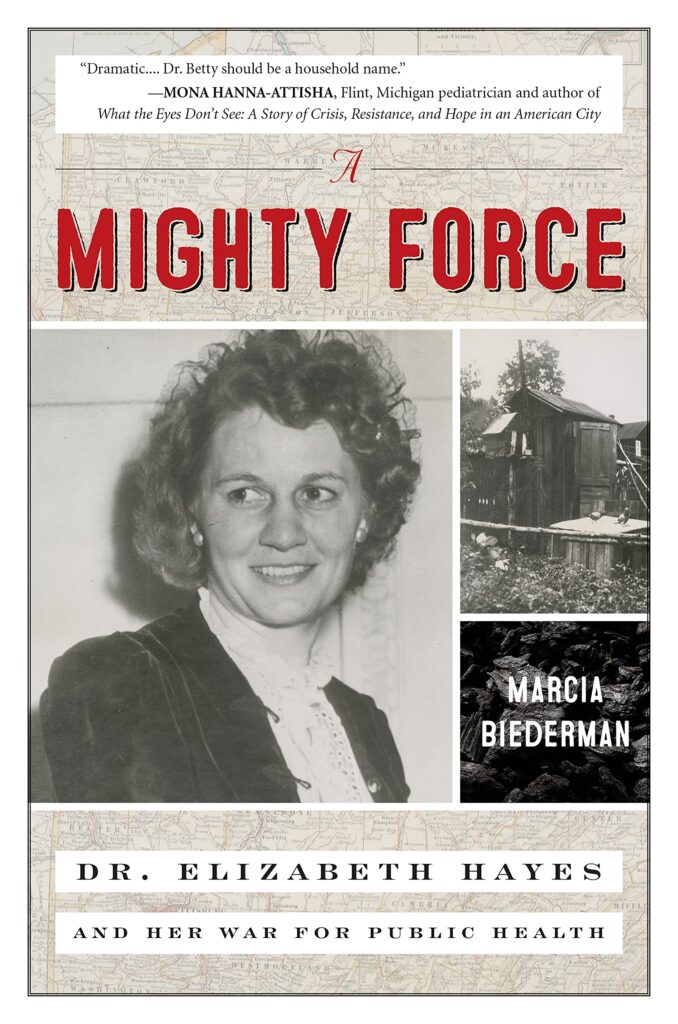

Marcia Biederman has contributed more than 150 articles to the New York Times, writing about everything from ice dancing to automobile wheel repair. Her work has appeared in New York magazine, the New York Observer, the Daily News, and Crain’s New York Business. A former mystery novelist, she’s the author of three biographies, Popovers and Candlelight: Patricia Murphy and The Rise and Fall of a Restaurant Empire (SUNY Press 2018), Scan Artist: How Evelyn Wood Convinced the World That Speed Reading Worked, (Chicago Review Press 2019), and A Mighty Force: Dr. Elizabeth Hayes and Her War for Public Health (Prometheus Books 2021).

Take it away, Marcia!

You write about women who were well known during their lifetimes (which were not that long ago), who had an impact on their world, and who are not well known today. Why do you think we forget the roles women have played in history so quickly?

As twentieth-century women, my biographical subjects had to buck prejudice about women’s roles to grab the public’s attention and approval, even temporarily. The two who were entrepreneurs, restaurateur Patricia Murphy and speed-reading marketer Evelyn Wood, had to market their brands relentlessly to gain recognition. Murphy drew record-breaking crowds to her enormous restaurants in New York State and southern Florida; Wood enrolled hundreds of thousands in her courses. However, their fame ended with the conclusion of the ad campaigns. Murphy’s restaurants never entered the annals of food history, the way the Four Seasons did. Wood’s brand lived on after her death, but many people thought of her as a fictitious figure, like Betty Crocker.

Both were in fields deemed appropriate for females – cooking and teaching – although Murphy couldn’t boil water, and Wood had spent little time in a classroom. But, if being women enhanced their brands in their lifetimes, it worked against them later on. Food critics and newspaper feature writers belittled Patricia Murphy’s Candlelight restaurant chain because its patrons were mostly female. In fact, late in her career, Murphy opened a men-only dining room in Florida to try to scrub off the “tearoom” taint. As for Evelyn Wood, until debunkers exposed her speed-reading method as a shame, she was one of the century’s great con artists. But no one recognized her as such. As we see today in the cases of Elizabeth Holmes and Anna Delvey, people are reluctant to believe that women can be scammers..

Erasure was completely different for my most recent biographical figure, Dr. Elizabeth Hayes, who in 1945 led 350 coal miners on a successful strike for clean water and decent housing in their company-owned town. In the final weeks of World War II, Hayes and the strikers dominated headlines. Every news outlet in the country, from the Socialist Call to Business Week, was rooting for “Dr. Betty’s miners,” as they were known. The “we-can-do-it” spirit of the times briefly blurred gender roles. Thirty-three years old, Hayes made a great 1940s heroine, taking on a powerful mining company with bold leadership and quotable quips.

But, unlike the women of my other two biographies, Hayes had never sought the spotlight, and she didn’t spend money on ads and publicists to keep herself visible. Hence, it was a fairly easy task for history to erase her. Her struggle inspired President Harry S. Truman to commission a medical survey of coal communities, but the admiral leading it didn’t acknowledge Hayes or invite her participation. For a while, she gave talks about the strike, eventually disappearing into private life. Like a meteor streaking across the sky, she had a brief moment of fame, which I had the privilege to discover and, I hope, revive.

You published mystery novels before you made the leap to writing non-fiction. Does your experience as a novelist shape how you write narrative non-fiction?

Yes, I’m definitely able to apply the techniques of mystery writing to my narrative nonfiction. I can’t make anything up, but I can find the drama in real-life events.

When I was having trouble with an early draft of one of my books, I scheduled a mentoring session with Cathy Curtis, a past president of Biographers International Organization who has written several amazing biographies of women. She advised me to look for a “Rosebud moment.” I immediately knew what she meant. Looking at the life I was chronicling, what was the person’s driving motivation? I also look for antagonists, reactions to setbacks, and big life-changing decisions.

There are some differences, though. Because the women I write are unknown to many readers, I begin with a prologue that establishes their importance. For Patricia Murphy, this was the launch of her memoir at Macy’s, where she set a record for the number of books signed. For Evelyn Wood, it’s at a teacher’s convention in Atlantic City, where teenagers demonstrating her speed-reading techniques wowed the crowds and sent reporters racing to their typewriters. For Dr. Elizabeth Hayes, it was the raiding of her medical office by enraged mining officials who forcibly evicted her, confiscating her stethoscope, patient records, and medications.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work

Like many Baby Boomers, I grew up thinking that all Americans pulled together on the US homefront throughout World War II. Sure, I knew about the black marketeers and other profiteers, but I thought the nation on the whole devoted itself to the war effort until V-J Day. Researching A Mighty Force, I discovered that a phenomenon called “peace jitters” was widespread. Toward the end of the war, Americans felt confident that the Allies would win, so they started jockeying for position in postwar prosperity. They quit defense jobs to seek positions in sales, for instance. Meanwhile, corporations were prematurely planning to ditch weapon-making so they could manufacture appliances instead. Alarmed, the federal government tried to enforce wartime restrictions, but there were ways around them. In other words, the Mad Men-style rat race started earlier than I thought.

Question for Pamela: If you had to recommend one biography of a woman to other biographers or aspiring biographers (not necessarily to all bio readers) what would it be and why?

You asked for one. I’m going to give you three because I think they offer different lessons. (They are all also compulsively readable.)

Nancy Marie Brown. The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women. This was one of the best books I read in 2021, and I’m recommending it to lots of people for lots of different reasons. Brown builds a possible life story for the Birka Woman—the Viking warrior remains that Swedish scholars proved were those of a woman, not a man as had been assumed for more than 130 years. The Real Valkyrie offers biographers is an object lesson in re-examining assumptions, using your imagination in looking for sources, and squeezing every drop of information out of the sources you have.

Helen Castor. Joan of Arc. Castor provides an excellent example of how to bring new life to a familiar subject, signaled in the use of “a history” rather than “a biography” as a sub-title. Instead of starting with Joan, she begins with the turbulent history of fifteenth century France, placing Joan’s achievements within the context of the bloody civil war that began with the assassination of Louis, Duke of Orleans, at the instigation of his brother, the Duke of Burgundy, in 1407. In doing so, she makes story of St. Joan more understandable, more complex, and more extraordinary.

Matthew Goodman. Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History Making Race Around the World. Eighty Days is more than an adventure story, though Goodman manages the difficult trick of maintaining suspense when the reader knows who wins the race. The lesson for biographers, though, is the way Goodman places his story in context. He does not limit himself to a step-by-step narrative of his heroines’ travels. Instead he uses the race to illustrate the social impact of new modes of transportation, a growing popular press, and new opportunities for women. The result is a social history of America on the verge of modernity. Personally, I believe this rich use of historical context is something every biographer should aspire to.

* * *

Want to know more about Marcia Biederman and her work?

Check out her website: Marciabiederman.com

Follow her on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AMightyForce

* * *

Come back tomorrow for a whole bunch of questions with biographer Debby Applegate.