Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

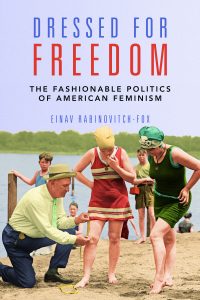

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox is a modern U.S women’s and gender historian who teaches at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, OH. Her research examines the connections between fashion, politics, and modernity, particularly the role of visual and material culture in social movements. Her recent book, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism explores women’s political uses of clothing and appearance to promote feminist agendas during the long 20th century. Her writing has been published in academic journals and books including the Journal of Women’s History, the International Journal of Fashion Studies, American Journalism: Journal of Media History, as well as popular media such as The Washington Post, The Conversation, Public Seminar, and History News Network.

Take it away, Einav!

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early to mid-twentieth century?

In a sense, the past is always a foreign country, and although we are less removed from the modern period, and are more familiar with it, I think some of the challenges remain. This is especially true when writing about women, as for so long, these histories were considered frivolous or not important, so I think that even when writing about women from the early to mid-twentieth century, there are still challenges in finding sources about them, or in finding sources that really center women’s voices and experiences. This is especially true with regards to women of color, working-class women, or other marginalized women, for whom there is still scarcity of sources.

Moreover, this sense of familiarity with the recent past can be deceiving. There is always the risk of interpreting things wrong or to draw conclusions based on our own experience and not necessarily on the experience of women in the past. Things have changed so dramatically in the life of women during the first decades of the twentieth century, that even for a woman living in the 1930s, the 1900s didn’t seem so liberating, not to mention for someone living in 2023. I always try to meet the women I write about where they are, to understand their world and how they were able to navigate it, and what challenges they had to overcome that maybe I don’t anymore.

Another thing to consider, especially when writing about more recent periods, is that the women I write about are perhaps still alive or have family members who are still alive. And while this is also true when writing about the distant past, I think that the real-life presence of women who lived in the recent past can bring more challenges to writing about them. I often feel I have more responsibility towards them to get the story right, but also to be more sensitive in how I tell their story. I also take into consideration what would be the repercussions of writing about personal or uncomfortable aspects of their lives. In that sense, it is the sense of familiarity that actually presents a challenge to distance yourself from the subjects of your writing.

Your work focuses on the way visual and material culture shapes and reflects class, race, and gender identities. What do we learn when we use images as more than just illustrations?

In a way, an image is just like any other historical source that can tell us something about the past. Especially when researching women’s history and other marginalized communities, what we often have is visual and material evidence, so it is actually a very important source to understand women’s history. Not many women left for us written records in the form of letters or diaries, but we can learn a lot about their everyday life and what they cherished and enjoyed from their dresses, embroidery, and small possessions.

Photographs, paintings, and illustrations contain a lot of information about the past, and so we need to learn to read them just like we read written sources. Material objects offer us even more information, as one can tell a lot when examining wear-and-tear of clothes, or use of other items. I think once we train ourselves to look at images more than just illustrations, but as historical sources, we can also begin to ask questions about them and discover that they can tell us a lot of things about the past.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

Writing about fashion, I got to do research not only in archives but also in costume collections, which are archives made of dresses and other clothing articles and accessories. The most surprising thing about it is how different dresses look and feel like in real life, compared to an image or an illustration. Looking at an actual garment: How it is constructed, from what materials, as well as how much of it worn and torn, can tell you a lot not only about the piece itself, but oftentimes also about the person who wore it, as items that arrive to costume collections are almost never anonymous.

One of the most exciting finds are the times that you can match an actual dress to an image of the person who wore it, or a description of them wearing it and how they felt in this garment. Yet, exciting finds can also happen when you get to feel and touch the garment and understand better issues of comfort and proportions, something that often gets lost in images.

One example of that, which to me was very surprising, was when I got to see a bathing suit from the 1920s in one of the collections I visited, which was in Smith College. Bathing suits in the 1920s were quite revolutionary at the time, because they exposed women’s hips and shoulders and were very revealing of the body. It even caused some municipalities to try and ban them on the beaches as they were considered “inappropriate” and even “immoral.” Bathing suits were really the symbol of a feminist consciousness and liberation in the 1920s, so imagine my surprise when I got to touch it, and discover it was made from wool, maybe the last material I would like to go into the water dress in. Realizing that bathing suits were made of wool not only made me appreciate the invention of Latex, but also got me thinking differently about what comfort meant to the women who wore these suits and what made them so revolutionary, and how we today judge comfort.

Question from Einav: You write historical works for popular audiences, how do you make your audience care about women’s history? How do you show them that women’s history matters, that it is important?

When I was writing my dissertation, I had a day job that required me to work with a great many tradesmen, many of whom had doubts about taking instructions from me. (Probably all of them had doubts at the beginning. Some of them were simply more polite about it than others.) I changed their minds one guy and one project at a time.

In many ways, making readers care about women’s history is very similar. Other than this annual series of mini-interviews, I don’t try to make my audience care about women’s history in the abstract. Instead, I do my best to make them care about a particular woman or group of women or a specific story. Part of doing that is to make it clear why that story and that woman matter and how putting them back into the historical record makes our understanding of the past richer.

***

Interested in learning more about Einav Rabinovitch-Fox and her work?

Visit her website: www.einavrabinovitchfox.com

Follow her on twitter: @DrEinavRFox

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a women’s-history- related blog post from me. (Subject to be determined.) But we’ve still got more people talking about women’s history from a lot of different angles next week. Don’t touch that dial!