History on Display: The Jane Addams Hull House Museum

A few days ago, My Own True Love and I took a few hours off to visit a museum that’s been on our list for several years now: the Jane Addams Hull House museum. Jane Addams (1860-1935) and Hull House stand in the center of a Venn diagram of many of our interests: historical women who made a difference, late 19th and early 20th century reformers in general and the settlement house movement in particular, Chicago history, and the immigrant experience in America.

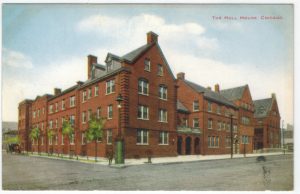

We were familiar with the basic story of Hull House: Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr were introduced to the concept of settlement houses, in which middle-class and upper-class reformers “settled” in group houses in poor urban neighborhoods, on a visit to London. On their return to the United States, they founded Hull House* in a densely populated, largely immigrant neighborhood in Chicago’s Near West Side. The settlement house offered a variety of social programs to neighborhood residents. All of which is true, but neither of us was prepared for the sheer scope of the Hull House project.

Hull House itself was only one of a multi-building complex that eventually filled an entire city block.** which is now part of the University of Illinois Chicago campus. Addams and Starr were the leaders of an extraordinary group of women—doctors, lawyers, artists, general shin-kickers—who made the world a safer, better place for women, children, blue collar workers, and immigrants. They helped lay the foundation for the field of occupational health and safety, helped pass laws against child labor, and published a report on conditions in their neighborhood that was the first to blame conditions in urban slums on economic systems rather than on the individuals who lived there. They pushed for an eight-hour work day and introduced art classes to the Chicago public schools. Addams won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931, but not every one saw their actions as positive. Addams had an FBI file. The DAR dubbed her the most dangerous woman in America. And the “female führer” Elizabeth Dilling gave her a listing in her infamous Red Network.

At the complex itself, Hull House offered classes in art and music, technical skills, cooking, sewing, and English as a second language. They offered a wide range of services to the neighborhood, including a nursery and kindergarten so working women would have childcare, a public kitchen that served 60,000 meals a year, public baths,** an employment bureau, a clinic, an art gallery and performance space. The complex housed a branch of the Chicago Public Library and the Jane Club, which provided housing for single working women. It also produced its own electricity, and sold the excess power to its neighbors.

The museum tells the story well, with artifacts, photographs, and quotations. You are urged to sit at Addams desk. And, in what is one of the most unusual museum programs I’m aware of, the Jane Addams Bedroom Project, UIC staff, faculty and students are invited to sign up to take a nap in Addams’s bedroom—a practical expression of Addams’s believe that play and rest were important.

If you’re in Chicago, the Jane Addams Hull House Museum is well worth a visit. If Chicago is not in your future, a virtual tour is available at the museum website.

*Named after Charles Jerald Hull, the original owner of the quite astonishing Italianate-style house, built in 1865, that was the heart of the settlement. Since we are old-house nerds as well as history buffs, we were occasionally distracted by the building itself.

** The block was taken over by the University of Illinois Chicago. Only the 1865 building, where Addams lived and worked remains.

***Soon after Hull House opened, Addams learned there were only 3 bathtubs in the 1/3 square mile east of the building. She had 3 public baths built behind the settlement which gave almost 1000 people a month access to baths that were previously unavailable.