Anne O’Hare McCormick: “Freedom Reporter”

Like Sigrid Schultz, Anne O’Hara McCormick (1880-1954) became a foreign correspondent because she was in the right place at the right time.

She already had experience as a journalist before she became a foreign correspondent. After her graduation from a private Catholic high school in 1898, she went to work for the Catholic Universe Bulletin in Cleveland, Ohio, , where she rose to the position of assistant editor.

In 1910, at the age of thirty, she married Francis J McCormick. Francis was a wealthy engineer who imported large equipment based in Dayton Ohio who traveled extensively in Europe for his job. Anne went with him.*

Like other working women of the period, Anne left her job when she got married,** but she continued to write occasional pieces on a freelance basis which appeared in magazines like Catholic World, Atlantic Monthly, and The Saturday Evening Post. In 1921, after a piece of hers titled “New Italy of the Italians” ran in the New York Times Book Review and Magazine, Anne, wrote to Carl Van Anda, managing editor of the Times, asking if she could write news stories for him from Europe. His answer: Try it.

Try it she did. Her first regular by-lined article appeared in the Times in February 1921: a piece about Sinn Fein titled “Ireland’s ‘Black and Tans’.” Anne soon became a regular freelance correspondent for the Times. (The paper’s publisher, Adolph Ochs, refused to hire women as staff correspondents.) Her lack of a staff position proved to be a blessing of sorts, Unlike staff foreign correspondents, who were assigned to a specific location, Anne was free to travel as dictated by her interests, or Francis’s business assignments.

Small, matronly, soft spoken and charming, Anne used her networking skills get interviews with any one who mattered, including Chamberlain, Hitler, Mussolini, and Roosevelt—even without the credentials of a staff correspondent. She occasionally covered a breaking news item, but for the most part she wrote in-depth think pieces for the Times‘ magazine that ranged in subject from political analysis—she was one of the first to predict Mussolini’s rise to power—to a comparison of street lighting in different European cities and what the differences said about them. She wrote stories about developments in the United States as well as in Europe, most notably pieces on the Florida real estate boom in 1925 and the “New South” in 1930.

In 1936, after Ochs’ death, his successor made her a full-time salaried “freedom reporter.” Her assignment was to travel the world and write three world affairs columns each week, reporting on conditions in places where she believed freedom was threatened. He also made her a member of the Times’ editorial board, a position she held until her death in 1954.

In 1937, she became the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for journalism for her dispatches and feature articles from Europe.***

She continued to report from abroad after the United States entered World War II. When the war ended, she served as a UNESCO delegate in 1946 and 1948.

*I spend a lot of time considering whether or not to call the subjects of my work by their first name. In the case of Sigrid Schultz, I chose to use her last name once she was an adult because I was uncomfortable first-naming her while I called her male colleagues by their last names. Since there are two McCormicks here, I have opted for Anne and, to the extent that he appears, Francis.

**Often they didn’t have a choice. Many employers refused to allow married women to remain on the job. (As I have pointed out before, this did not apply to women working as household servants or other working class jobs. It is all too easy to view the history of women at work through the lens of the middle and upper class experience.)

***She was not, however, the first woman to win a Pulitzer. That honor belongs to two sisters, Laura Elizabeth Richards and Maude Howe Elliott, who collaborated on a biography of their mother, Julia Ward Howe. They were awarded the very first Pulitzer in biography in 1917.

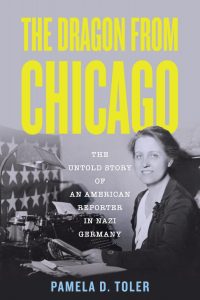

My publisher is giving away 25 copies of The Dragon From Chicago on Goodreads. You can sign up here through July 4. Good luck!

Although she wasn’t a journalist, author Pearl

Buck, best known for “The Good Earth,”

was the first woman to win the Nobel for literature and a Pulitzer. She was an incredible woman and was highly instrumental in introducing the Western world, especially Americans, to the lives of ordinary Chinese people. She lived an amazing life. Peter Conn’s bio, “Pearl Buck, A Cultural Biography”’is a must-read for anyone interested in China or the life of this amazing woman. She is buried on the grounds of her American home in Perkasie, PA. Well worth a visit if you ever have the opportunity. Pearls’s Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes are on display, as well as the typewriter on which she wrote “The Good Earth” as well as many other her large bodies of work.