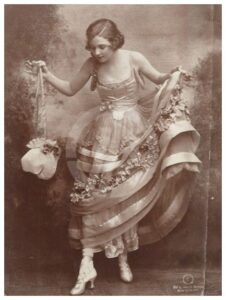

Lady Duff Gordon, aka Lucile

I honestly thought I had written my last post on changes in ladies’ lingerie. Then Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon (1863-1935) floated across my path in one of the romantic and subtly sexy gowns with which she wowed the fashionable world at the turn of the twentieth century. I was already familiar with Lucile’s trademark tea gowns and evening dresses. It never occurred to me that her (relatively) insubstantial dresses would need something different in terms of underwear. But of course they did.

Lucile, then Lucy Wallace (née Sutherland), entered the “rag trade”in 1890 because she was desperate for money when her alcoholic husband, James Stewart Wallace, abandoned Lucy and their daughter. Lucy moved in with her mother and she began supporting herself as dressmaker. When one of her dresses was a hit at a weekend house party, her career took off. In 1894, after divorcing James Wallace, that nice little dressmaker Lucy Wallace turned herself into the mononymous Lucile, owner of the exclusive Maison Lucile, which catered to a wealthy clientele that included aristocracy, socialites and stars of the film and stage, such as Lily Langtry, Ellen Terry, Sarah Bernhardt, Mary Pickford, and Irene Castle. A few years later, Lucile married, Scottish baronet Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon. Already a celebrity as a couturier, her new title added additional cachet to her career.

Lucile was best known for her tea gowns, evening dresses, and luxurious lingerie. She dubbed her evening gowns “Gowns of Emotion”, and gave them evocative, if not very descriptive, names like “Give Me Your Heart” and “The Sighing Sounds of Lips Unsatisfied.” The gowns were made with floating layers of diaphanous fabrics in pale colors, soft drapery, and dramatic asymmetrical effects. They had low necks, and slit skirts, daring and scandalous at the time. The lingerie that went under her dresses was sheer, trimmed with tiny hand-made silk flower, and provocative—no boned corsets under a Lucile gown!

Lucile made more innovations in the world of fashion than just her dresses. She was the first couturier to train lovely young women as professional models. She originated the “mannequin parade” as a technique for displaying her gowns and luring women into placing orders. Invitation-only, the parades were important social events. * For most of the year, the parades were held at Maison Lucile, but in the summer Lucile held the fashion shows in her garden, where models walked pedigreed dogs with jeweled collars and leashes.

Over time, Lucile transformed Maison Lucile into the first successful international couture business, Lucile Ltd., with houses in London, New York, Chicago and Paris. Beginning in 1910, she wrote weekly columns for the Hearst newspapers and monthly columns for Harper’s Bazaar and Good Housekeeping. In addition to creating gowns for famous actresses, she designed costumes for theatrical productions, including the operetta The Merry Widow, several productions of the Ziegfeld Follies, and more than eighty movies. For a brief time she also had a successful mail-order business with Sears, Roebuck, offering a lower-priced, mass-produced line with her name.

During World War I, Lucile closed her couture houses in London and Paris and based herself in New York. Her business did not revive after the war. Fashions had changed and Lucile’s trademark romantic style seemed old-fashioned compared to the bold new fashions of the flapper era. Lucile Ltd. closed in 1922, though Lucille herself continued to design for private clients in London.

A few odd tidbits:

Lucile was the older sister of novelist, screenwriter and film producer Elinor Glyn, who popularized the terms “It” and “It Girl.”

Together with her husband, her maid, and nine other people, Lucile survived the sinking of the Titanic in boat designed for forty. The Duff-Gordons were cleared of charges of having bribed crew members to not allow others on the boat, but Sir Cosmo’s reputation was permanently smeared. Lucille seems to have gotten off more lightly in the public eye: on the day that she testified at the public hearing about the disaster , the room was packed with society women wearing their Lucile creations in support of their favorite designer.

*Women came to look at their dresses. Unattached young men—ostensibly escorting their mothers, aunts, grandmothers, and old family friends—came to look at the models.

She was my grandfather’s Sutherland cousin, so mine, twice removed I guess. I’m fascinated by both Lucy and her sister Elinor.