1925: A Year in Review

In historical hindsight, the big event in 1925 was Adolf Hitler’s publication of Mein Kampf and re-organization of the National Socialist party[1] to emphasize the the extreme nationalism that is a common element of fascist political philosophy rather than its original socialist leanings.

In fact, in 1925, the Nazis were not yet a significant political power and what Germans call Die goldenen zwanziger Jahre (The Golden Twenties) was at its height. The economy was on its way to recovery from the hyperinflation that had plagued it since 1923 , thanks to the passage of the Dawes Plan in 1924, which put the German economy under foreign supervision and stabilized the mark. The political landscape was relatively calm, on the floor of the Reichstag if not in the streets,[2] under the strong leadership of Gustav Streseman[3]. General Paul von Hindenburg, having reluctantly agreed to run for president, won by a huge margin, giving the illusion of national political unity. The country was enjoying an artistic intellectual blossoming that was dynamic, challenging, and transgressive. In short, Germany seemed to be stable.

Meanwhile, in the United States:

On March 18, the Tri-State Tornado, the deadliest tornado in United States history tore through southeast Missouri, southern Illinois and southwest Indiana, leaving 695 people dead, more than two thousand injured thousands homeless, and $16.5 million in property damage.[4].

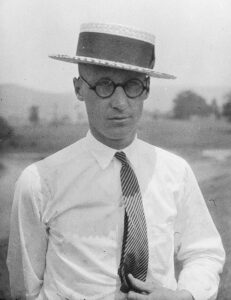

- Clarence Darrow

- John T. Scopes

- William Jennings Bryan

In July, Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryant squared off over the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools. Dubbed the Scopes Monkey Trial by journalist H.L. Mencken, the case began as an effort by the ACLU to test whether the Butler Law which made such teaching illegal in Tennessee, was constitutional. The ACLU ran ads in Tennessee newspapers offering to pay the legal expenses of any teacher willing to challenge the law. Twenty-four year old high school teacher and football coach John T. Scopes stepped up, backed by a group of local residents eager to put their economically depressed town in the news. It worked, for more than a week, Dayton, Tennessee, was the center of the nation’s attention. Reporters came from as far away as London and Hong Kong to report on the trial. More than six hundred spectators crowded into the courtroom each day. Thousands more listened to a live radio broadcast from the courtroom—the first such broadcast to be made. It took the jury nine minutes to find Scopes guilty. He was fined $100. The Supreme Court of Tennessee overturned the verdict on a technicality, but ruled the Butler Law to be constitutional. In 1968, the United States Supreme Court found a similar law in Arkansas to be a violation of the First Amendment. (Change is slow.)

Elsewhere in the world:

On January 3, Benito Mussolini effectively declared himself dictator of Italy in a speech to the Italian parliament, after a nudge from his party members, who felt he was moving too slowly in his efforts to dismantle Italian democracy from within.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk abolished Islam as the state religion in Turkey—the first step in a series of reforms designed to secularize the Turkish state, including the abolition of polygamy, the prohibition of the fez, the modernization of women’s clothing , and adoption of the Latin alphabet.

A fragile alliance had existed between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party after the 1912 revolution that established the Republic of China. With the death of charismatic revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen on March 12, 1925, and the ascension of Chaing Kai-shek to the head of the Nationalists, ideological differences between the two parties intensified, leading to a brutal civil war between them from 1927 to 1949.

France occupied Syria and Lebanon in the early 1920s as part of the League of Nations’ mandate system. The mandates were intended to be a temporary arrangement designed to administer former German colonies and Ottoman territories with the goal of eventual independence. Not surprisingly, the mandate quickly looked a great deal like colonialism, including economic extraction that benefited France and not the mandated territories, with no sign of independence in sight. In the summer of 1925, what became known as the Great Syrian Revolt erupted in Syria and Lebanon. The French responded violently. In October, the revolt caught the world’s attention when revolutionaries attacked the French troops in Damascus. The high commander of the French miliary administration decided to take drastic measures against the revolutionaries and ordered troops to bombard the city. After nearly twenty-four hours of heavy fire from French airplanes and tanks, much of the city was in ruins. The violence marked a turning point in discussions about European colonial dominance and humanitarian aid in Syria, with Geneva as the center for the debate. For a time, there were calls to remove the mandate from French control. Those calls ultimately failed. By 1927, the revolt had been brutally quashed.

In a step toward greater democracy, Japan introduced universal male suffrage.[5] On the other hand, Japan also passed the Peace Preservation Law in 1925. This law gave the government the power to limit political dissent, providing the foundation for the militarism of the 1930s.

A few non-political things to end on a high note:

F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby

The Grand Ole Opry began broadcasting from Nashville

The first surrealist exhibition opened in Paris

John Logie Baird transmitted the first recognizable black and white television picture on October 2. The following January, he gave the first public demonstration of television.

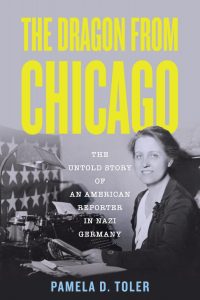

And, ahem, Sigrid Schultz became the Berlin bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune.

[1] The term Nazis didn’t come into common use until 1931. Prior to that they were referred to as National Socialists, Hitlerites, or small-f fascists.

[2] Violence in the streets was a regular feature of German political life in the period between the two world wars.

[3] A successful businessman before he entered politics, Gustav Streseman was the head of the liberal German People’s Party. After a brief term as chancellor in 1923, he served unchallenged as the Weimar Republic’s foreign minister until his unexpected death at the age of fifty-one in 1929, shortly before the American stock market crashed and took the German economy with it. In my opinion, Germany’s response to the Great Depression might have been very different if Streseman had been there.

[4] $28.6 billion today

[5] Women didn’t get the vote until 1945.