You Could Look It Up

I am a reference book junkie. I collect reference books the way some people collect Fiesta Ware, Oriental rugs, salt shakers, or black pumps.* I argue that they are useful to me in my career. And sometimes it's true. (The construction dictionary that I bought more than 25 years ago is proving useful in my current project.) But the immediate needs of my writing career provides no explanation for the itch to acquire, for example, an English to Polish dictionary or an encyclopedia of gods or an historical atlas of Byzantium or--well, you get the idea.

I am a reference book junkie. I collect reference books the way some people collect Fiesta Ware, Oriental rugs, salt shakers, or black pumps.* I argue that they are useful to me in my career. And sometimes it's true. (The construction dictionary that I bought more than 25 years ago is proving useful in my current project.) But the immediate needs of my writing career provides no explanation for the itch to acquire, for example, an English to Polish dictionary or an encyclopedia of gods or an historical atlas of Byzantium or--well, you get the idea.

Thanks to author Jack Lynch, I now have a grander explanation for my fascination with reference books.

In You Could Look It Up: The Reference Shelf From Ancient Babylon to Wikipedia, Lynch argues that reference books are "a civilization's memoranda to itself".** In looking at a society's reference books you learn not only the facts contained therein, but something about what that society valued. (Or what some of a society's members valued: the annotated list of prostitutes from eighteenth century London, for instance, had a specific audience.***)

Each chapter pairs two works dealing with similar topics—words, medicine, games, the arts--and places them in historical context. Lynch begins with the ancient law codes that are our oldest reference books and ends with modern books of trivia, which transform the reference book from a compendium of essential knowledge to an amusement for browsers.

The stories of the individual books are fascinating in and of themselves. (The Guinness Book of World Records began as a promotional item designed to settle drunken wagers in pubs.) But some of the most startling revelations come in the form of what Lynch dubs "half-chapters", short essays in which he investigates broader topics related to reference books, including the antiquity of complaints about information overload, the relative late adoption of alphabetizing as an organizational structure, and the introduction of deliberate errors by reference book editors.

In the end You Could Look It Up is a history not simply of reference books as a genre but of the broader question of how we organize information and why.

The guts of this review first appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

*By which I mean shoes, not the working end of a well. Though I suspect that someone somewhere collects black pump handles. The collecting passion is idiosyncratic, personal, and occasional inexplicable.

**Now there's an excuse for reference book acquisition!

***I suspect some of my friends who write Recency and Georgian romance would love to get their hands on a copy. (Gina Conkle, I'm looking at you.)

From the Archives: Lincoln’s Greatest Case–Sort Of

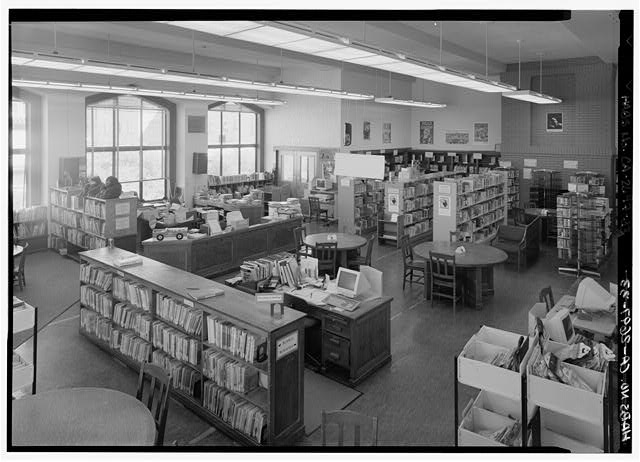

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Brian McGinty (The Oatman Massacre) uses his skills as both attorney and historian in Lincoln's Greatest Case: The River, The Bridge and The Making of America.

In May, 1856, the steamboat Effie Afton hit a pillar of the Rock Island Bridge--the first railroad bridge across the Mississippi. Both steamboat and bridge caught fire. The Effie Acton sank, with all its cargo. The Illinois side of the bridge collapsed onto the wreck of the steamboat the next day. In the trial that followed, the powerful steamboat interest fought the developing railroad industry for control of the Mississippi, and the nation's shipping business.

McGinty sets out the complicated story with the clarity of a legal brief. He places the trial and its issues solidly in a historical context that includes the role of the Mississippi in American economic life, the Dred Scott case, Abraham Lincoln's career, and westward expansion. He leads readers through the intricacies of legal principles governing interstate commerce and judicial jurisdiction, steamboat operation, bridge construction and river currents with a sure hand. He reports the day-to-day unfolding of the trial with an eye to both the personalities and the issues involved.

Lincoln's Greatest Case tells an intriguing story that will appeal to anyone interested in the commercial and industrial history of the United States, but the title is misleading. Anyone expecting a courtroom drama with Lincoln at its center will be disappointed. There's a reason the Effie Afton trial is little more than a footnote in most Lincoln biographies: Lincoln was not the lead attorney in the team defending the Rock Island Bridge. He is simply the best-known character in a colorful cast.

This review originally appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

What Did Civil War Nurses Do After the War?

The Civil War was a pivotal experience for many of the women who served as nurses, whether they served for three weeks or three years. For many it was their first time away from family and home, and their first step outside the narrow framework of what society expected from them. They learned not only new skills but also new confidence. Whether in the immediacy of letters at the time or with the distance of memory, they expressed deep satisfaction with the work and the way of life, though they often groused about a particular detail. Katharine Prescott Wormeley, who served first on the hospital transport ships and later as the matron for a hospital for convalescent soldiers in Rhode Island, claimed to speak for the army nurses as a whole: “We all know in our hearts that it is thorough enjoyment to be here,—it is life, in short; and we wouldn’t be anywhere else for anything in the world.” Emily Parsons, who served as a nurse for two years at a variety of hospitals despite being blind in one eye, partially deaf, and lame, took the sentiment one step further: “I should like to live so all the rest of my life.”

Parsons, like most of the women, and the soldiers they cared for, went home at the war’s end. Nursing had been a temporary part of their lives, just like being a soldier was a temporary part of the lives of most of the men who served in the war. Many stepped back into their old lives as daughters, seamstresses, schoolteachers, and wives. Others created lives that were a little bigger than they had been before the war.

Some made a living writing. The most famous of these was Louisa May Alcott, whose account of her Civil War experience, Hospital Sketches, was the first work she published under her own name.

A few women who served as nurses during the war went on to earn medical degrees. Vesta Swarts, for instance, was a high school principal in Auburn, Indiana, before the war. She nursed at Louisville, Kentucky, from sometime in 1864 until March 1865, when she was honorably discharged, a fact she mentions with pride in an essay she wrote on her war work. After the war, she became a physician--a challenging proposition for women--and returned to Auburn, where she practiced medicine with her husband for the next thirty years.

Many of the middle-class women who volunteered as nurses were part of the large and varied community of American reformers before the war. Their wealthier counterparts often came from families who expected them to take part in high-profile charity work. After the war, both middle-class reformers and wealthy philanthropists used their newfound experience at organizing, political activism, and manipulating their way through male-dominated bureaucracies to expand their influence. Some took on new leadership roles at the local level. Parsons, for instance, organized a campaign to open a charity hospital for women and children in Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. A few used their experience as a springboard to national leadership roles, founding groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union, the American Social Science Association, and the American Red Cross. They involved themselves in opening schools, reforming prisons and asylums, improving conditions for women and children, “saving” unmarried mothers and their children (both in moral and practical terms), and providing vocational training for girls. Some became active in the labor, women’s rights, and temperance movements, which expanded after the war to fill the political and emotional space previously occupied by abolition. Others spearheaded social welfare programs designed to alleviate the human misery left by the war. They formed relief funds for war widows and orphans, and programs to settle unemployed veterans on farmland in the West, and schools for former slaves. Cornelia Hancock, for instance helped found a freedman’s school in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, where she taught ex-slaves for a decade. (Not as innocuous as it sounds. At one point those who objected to the concept of education for black children riddled the schoolhouse with fifty bullets.) Several decades after the war, they used those same skills to advocate for themselves. Arguing that they too had served their country, they successfully pushed through the Union Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892, which provided government pensions for army nurses similar to those given to Union soldiers.

The one thing few of them did was work as nurses.

But if they didn't continue to work as nurses after the war, their collective experience in the war had convinced Americans that nursing was not only a respectable job for a woman but that it could be a skilled profession.

In 1868, the American Medical Association recommended that general hospitals open schools to train nurses. It was a two- edged response to the success of volunteer nurses in the Civil War. The AMA both acknowledged the value of skilled nursing in hospitals and hoped to avoid another flood of untrained and uncontrollable volunteer nurses in future wars. By 1880, there were a total of 15 nursing schools in the United States; by 1900, there were 432. Nursing had become recognized as a skilled profession.