Road Trip Through History: The Althing, or Medieval Democracy (More Or Less) In Action

We visited the national park at Thingvellir, aka the Assembly Plains, on what our Icelandic hosts assured us was a rare perfect day: sunny and warm enough that we peeled off not only our rain coats but our heavy sweaters.

Located in a geologically unstable rift valley where the American and European tectonic plates meet,* Thingvellir has been described as the heart of Iceland. It was the site at which the 36 chieftains of Iceland, accompanied by their families and followers, met each year for the Althing, or General Assembly, to settle disputes and debate the law. The gathering centered around Iceland's only elected official, the lawspeaker, who recited one-third of Iceland's law code each year in a natural amphitheater known as the Law Rock. But the Althing was more than just a legal gathering, it was a two-week-long market, fair, sporting event, and nationwide party. Sometimes it was a nationwide brawl. Anyone who could come did: thousands of them.

The Althing was a political force from 930 CE to the thirteenth century. As chieftaincies merged through inheritance, purchase, trickery and outright seizure, power between the chieftains became increasingly unbalanced; the gathering became less an exercise of democracy and more an exercise of law by battleaxe. In 1262, hoping for greater stability, the chieftains of the Althing gave away their independence and swore allegiance to King Hakon of Norway. The original Icelanders who fled Norway to avoid the rule of the first Norwegian king were no doubt cursing and kicking the walls in Valhalla.

In the nineteenth century, when Iceland** was caught up in the same Romantic nationalism that swept through Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire,*** young Icelanders took up the Althing and the Sagas as a symbol of Iceland's heroic and independent past. Thingvellir became the site for nationalist debates and on June 14, 1944, half the country traveled there to hear Iceland's declaration of independence from Denmark.****

Today,the Icelandic parliament is known as the Althing and Thingvellir is the site of Iceland's national celebrations. It is a place of incredible beauty, with a few discreet historic markers for those interested in its past and well laid out trails for those interested in a long walk. Just don't count on a warm dry day, even in July. Sweaters and rain gear are recommended.

*And are now parting company at the rate of 1/4 inch a year, suggesting that eventually Iceland will be torn in two by its own geology. (Interestingly, Kenya's Great Rift Valley is not technically a rift valley in geological terms. The things you learn when you go a-roving!)

**Then part of Denmark rather than Norway. Scandinavia's political history is complicated.

***Note to self: write the dang post on Romantic nationalism.

****Which was occupied by the Nazis at the time and in no position to fight to keep control of a rocky island the size of Kentucky.

Image courtesy of Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons, License CC-BY-SA 4.0

Road Trip Through History: Reykjavik

My Own True Love and I started and ended our Viking history adventure in a city no Viking ever saw: Reykjavik, literally Smoky (or perhaps steamy) Bay. It is fundamentally a grey city, built of concrete, stone and glass in an array of textures and shapes that save it from bleakness and livened by shots of pure color in the form of small houses made of corrugated metal,* lavish flower beds, and brightly colored rain-gear.

The thing that struck me most about Reykjavik is how modern it is--literally.

According to the party line, Iceland was settled in the 9th century by refugees from Norway, where Harald Fair-Hair had made himself the first king and was busy claiming all the land for the crown.** But the early settlers didn't build towns. They came together each spring in the great gathering known as the Althing to settle disputes and define the law. In later centuries, Icelanders formed temporary settlements along the coast during the fishing season. But all of these settlements scattered when their purpose was done.

Reykjavik the city--as opposed to Reykjavik the chieftain’s manor--was founded in 1751 by a representative of the Danish crown, making it the first permanent town in Iceland. (Just to put this in context: Boston was founded in 1630.) As late as 1845, the city’s population was no more than 1000. Like all colonial cities, it was based on trade. In the case of Reykjavik, that meant cod, first dried and later salted. ***

And speaking of cod, here are some of the highlights of our time in Reykjavik:

- The Maritime Museum focuses on the fishing industry in Icelandic history, from the days when Icelanders built six-oar boats from driftwood and fished with individual lines to modern freezer trawlers. I was particularly taken with an exhibit on Icelandic seawomen from the medieval period to the present. Fascinating stuff.

- 871 +/-2 --a small museum based on an archaeological site that deserves (and will get) its own blog post

- A city-walk led by a self--defined "history graduate": the tour guide was smart, informed, opinionated, and funny. I highly recommend this even for those with no particular interest in history. (Not that this describes any of the Marginites, but you might travel with anyone like that.) They also run a tour called Walk The Crash, led by an economic historian (we really wanted to take it, but we couldn't make the schedule work) and a pub crawl. Here's the link for anyone planning an Iceland trip: http://citywalk.is/

- Licorice. I am not a big licorice fan, but Icelandic licorice is good stuff. And a good thing, too, because the chocolate is forgettable.

*I was astonished to learn that the corrugated metal buildings date from the nineteenth century. I think of it as a modern material. Shows how much I know.

**As always with foundation myths, you have to take this one with a “yes, but”. It is clear that explorers from Norway reached Iceland once or twice before Ingólfur Arnarson established himself on the future site of Reykjavik. Even more interesting from my perspective, there is some evidence that monks from Ireland or the Scottish islands were already in Iceland when the Norwegian settlers arrived, presumably having traveled overseas in their coracles-- small round boats made of willow covered with skin and tar that make Viking longboats look like ocean liners. It is not clear whether the Vikings killed the monks or simply drove them off.

***Fishing is still important in Iceland, but tourists have replaced cod as the country's primary industry.

In Search of Sir Thomas Browne

There are times when the book I read isn’t the book I think it’s going to be.* This happened to me recently with science writer Hugh Aldersey-Williams’ In Search of Sir Thomas Browne. I expected a biography. And I had Browne confused with someone else altogether, though I am no longer sure who. Possibly Robert Burton, the author of The Anatomy of Melancholy?

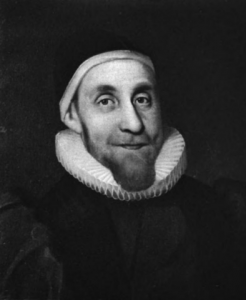

- Sir Thomas Browne

- Robert Burton

I got a quirkier and more interesting book than I was expecting.

In Search of Sir Thomas Browne: The Life and Afterlife of the Seventeenth Century's Most Inquiring Mind is neither a biography of Browne nor a critical study of his writings. Instead it is the intellectual equivalent of a buddy road trip.

Aldersey-Williams became interested in Sir Thomas Browne--a physician, scientist and debunker of popular myths--more than 20 years ago. In the intervening years, he found himself stumbling over Browne at unexpected moments. Finally, feeling "haunted" by Browne, he decided it was time to haunt Browne in return. Using Browne's writings, rather than his life story, as a framework, Aldersey-Williams travels in the physician's footsteps, both literally and intellectually. He looks for traces of Browne's life in modern Norwich (home to both men) and explores the echoes left by Browne's varying preoccupations in modern thought. He explores questions of scientific certainty, uncertainty and error, the meaning of order in nature, the reconciliation of science and religion, and the extent to which truth is knowable. He uses Browne's fascination with the recurring form of the quincunx,** his efforts at cataloging the birds of the Norwich marshes and his role as the expert witness in a witch trial as tools for understanding the intellectual landscape of both the 17th century and the modern world.

In the end, Aldersey-Williams argues that Browne is important not because of his answers or his baroque prose style, which inspired writers as diverse as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Jorge Luis Borges, but for the questions he asks.

* I’m not the only person this happens to, right?

** An arrangement of five objects with four at the corners of a square or rectangle and the fifth at its center

Most of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.