Operation Cornflakes

On February 5, 1945, near the end of WWII, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) began a widespread propaganda campaign in Germany with the unwitting help of the German postal service.

As a first step, Allied bombers derailed a German mail train, scattering its cargo in the process. A second wave of bombers followed and dropped eight mail bags, each filled with 800 properly stamped propaganda letters addressed to homes and businesses in the northern Austrian towns to which the train made deliveries. The idea was that when the postal service realized the train had been derailed, the Germans would collect whatever mail had survived the bombing, including the faked letters containing propaganda, and deliver it to German homes as regularly scheduled. In most cases, the delivery occurred at breakfast time, resulting in the code name Operation Cornflakes.

In preparation for the operation, OSS operatives collected samples of German mail, including stamps, cancellations, and envelopes, and compiled lists of German names and addresses from telephone directories. Propaganda that traveled through the German mail system included an OSS-produced newspaper that claimed to be the work of a growing German opposition party,* letters supposedly written by Nazi party leaders about Hitler’s ill health, and by generals who wanted to surrender. Together, the pieces were designed to create doubt in the minds of the civilian population and to weaken German morale.

Over the course of the operation, the allies dropped 20 loads of fake mail, with a total of 96,000 pieces of mail. A unit in Rome addressed 15,000 envelopes a week. Groups in Switzerland and England created the newspapers and letters and forged stamps.**

The operation eventually failed because of a typo. The return addresses on the envelopes were all those of legitimate German businesses. An OSS operative, perhaps with a cramping hand or aching eyes after hours of addressing envelopes, misspelled Kassenverein as Cassenverien on several envelopes. An alert postal clerk caught the error and brought it to the attention of his superiors. The envelopes were opened, and the propaganda discovered.

Did the operation have an effect on German morale? No one knows. But from a strategic perspective, Operation Cornflakes played a valuable role by putting additional strain on Germany's communication and transport system.

*It is unlikely that any Germans would have believed this, given that the Nazi party had gained control of the German press at all levels within a year of taking power.

**Including stamps that weren’t standard. If you look closely, you’ll notice some creative changes that wouldn’t have passed by an alert censor.

Before the Rockettes

Thirty-six years before the original Rockettes appeared on a St. Louis stage in 1925,* a failed cotton magnate named John Tiller formed a dance troupe that featured quick, perfectly synchronized dance steps. By the 1920s, several dozen troupes of Tiller Girls, selected for uniform height and weight, performed in major cities across Europe. They were so popular that European revue directors formed similar troupes.

Lines of pretty women dancing, or at least posing, had been a staple of variety revues for years. The thing that made the Tiller Girls different from earlier chorus lines was their speed and precision, which many theater reviewers compared to the dynamism of the modern era. Tiller had created a human equivalent of the factory machine, with dancers as interchangeable parts in coordinated kick-lines.

*Yes. St. Louis. The Rockettes first hit Radio City Music Hall in 1932. I was surprised, too.

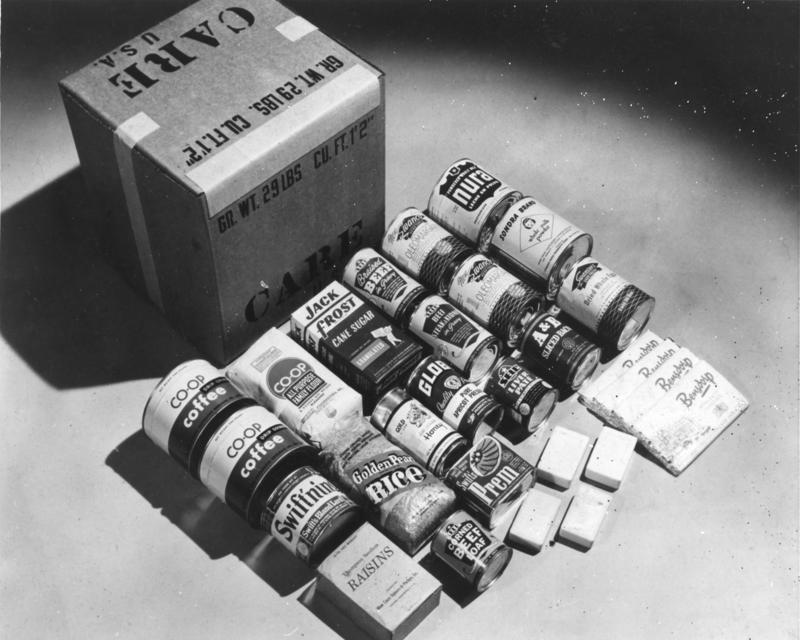

Word With a Past: Care Packages

When World War II ended, Europe faced a serious food crisis. Millions of people had suffered from malnutrition during World War II.* Cities were destroyed. Agricultural areas were not only ravaged by troop movements, but tainted by the remains of the dead and dying. (In the Falaise Pocket, for instance, it was two years before people could plant crops in the fields because the ground water was polluted with the remains of men and horses. )

The Marshall Plan was designed to help Europe rebuild, but it didn’t deal with immediate need on an individual level.

In November, 1945, seven months after the war ended in Europe and two months after it ended in the Pacific, Arthur Ringwald and Dr. Lincoln Clark worked with 22 American charitable organizations to create a non-profit corporation to send food packages to Europe.** Alice Clark suggested they call it “Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe”: C.A.R.E.

The first C.A.R.E. packages were surplus rations that the U.S. military had been stockpiling in anticipation of invading Japan. C.A.R.E. acquired 2.8 million surplus rations known as “10-in-1”—designed to feed ten men for one day. These boxes included not only canned meats, egg powder and dried milk, but items like coffee, chocolate and sugar which were luxury items to starved Europeans. (Among which we must include the British, who were better off than most of Europe but continued to suffer from shortages as late as 1945.)

The first 15,000 C.A.RE. packages arrived in the French port of La Havre on May 11, 1946—almost exactly a year after V-E Day. By the end of 1946, C.A.R.E was delivering packages in ten European countries. As the supply of rations began to dwindle, C.A.R.E partnered with American food companies to fill its boxes. Americans could send a package to individuals or families for $10. At first the recipients of packages were family and friends of the senders; as the program grew more popular, the organization began to get orders for recipients such as “a hungry occupant of a thatched cottage.”

CARE still exists—the E now stands for everywhere. It still works to eradicate hunger and child malnutritions. But it no longer delivers individual packages to those in need.

For millions of families, C.A.R.E packages were literal life savers in the years after the war, a gift of both food and hope. By the time I was in college, and probably earlier, C.A.R.E packages had evolved into care packages—not quite the same thing but still sent as a token of love and, well, care.***

*An estimated 20 million people died of malnutrition during the war: more than died in combat.

** Herbert Hoover led a similar movement after the first World War. Yes, Herbert Hoover.

***My personal favorite was a package I received long after college. One winter in my late twenties or earlier thirties, I received a box of paperback novels from my parents when I was down with pneumonia. Food for the soul.