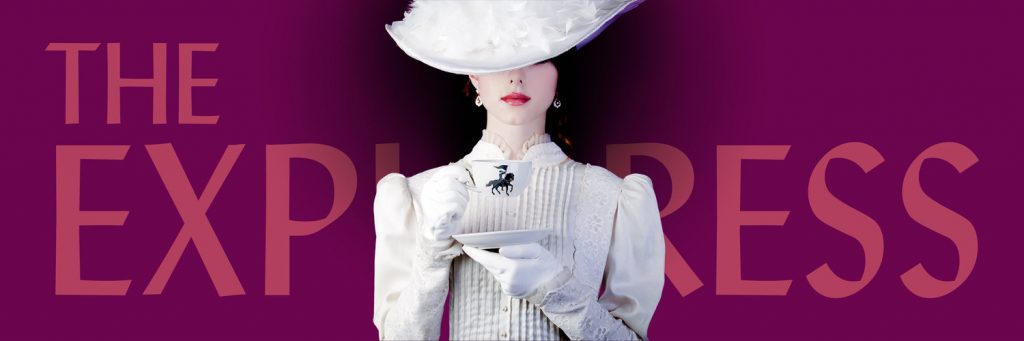

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with The Exploress

I want to make one thing clear right up front: I LOVE the Exploress podcast. I subscribe to many podcasts, but there are only a few that I support via Patreon and that I listen to as soon as an episode goes live. The Exploress is one of them.

Each season, Kate Jermain chooses a time period and then digs in “to explore not just the specific lives of fabulous women, but their world, and the myriad ways women lived in them” —a process she describes as “creative time traveling.” If you like your history smart, funny, focused, and a little bit snarky, you might want to check out The Exploress podcast.

The Exploress herself, Kate Jermain, is a writer, editor and teacher. When she’s not time traveling through her podcast, she edits and contributes to big pretty books for publishers like National Geographic.

Take it away, Kate!

If you could pick one woman from history to put in every high school history textbook, who would it be?

For American textbooks, I’d pick Elizabeth Keckley. This woman spent her formative years toiling under the yoke of slavery, suffering all of its horrors. But still, no matter how many times she was told she wasn’t worth much, she built her skills as a dressmaker and use them to buy her way to freedom. She found a way to transcend the life she’d been born into, creating a new life for herself in Washington, D.C., where she became dressmaker to the most influential female political/social stars of the day. With warmth, charm, and excellent business sense, she made dresses (and became friends) with women like Varina Davis, later first lady of the Confederacy. She became the First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln’s best friend.

She lost her only child in the Civil War, and yet she found the strength to nurse Abe and Mary Lincoln’s child when he fell deathly ill. She spent a lot of time surrounded by wealthy white people, but she also used her position to raise money for the “contrabands” (escaped slaves) that were regularly pouring into her adopted city. Later, after Mary Lincoln essentially dragged her into a public scandal, she tried to vindicate herself and her friend by writing a memoir: something very few African American women were doing. Her story is beautifully written and incredibly unique, but it also has a lot to tell us about the African American experience at this time in history. It must have taken such bravery to write about her life so honestly. Its reception has a lot to tell us, too: white readers at the time were horrified that the ‘hired help’ would dare to air the ex First Lady’s laundry in public. Mary Todd Lincoln never spoke to her again, and this brave, amazing womAn died in poverty.

It’s got everything: drama, intense high and lows, struggle and triumph. But more than that, it’s an incredible window into a pivotal time in America’s history: those final years of slavery, the horrors of the Civil War and the uncertain period after it, and one woman’s attempts to understand and survive. Her story is both haunting and inspiring, and all young American women (and men) should learn about it.

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

I LOVE telling the stories of everyday women doing extraordinary things: building bombs, sneaking their way into armies, discovering stars. It’s particularly exciting when I stumble on something I’d never heard about before in the realm of women’s history: for example, how 19th century Spiritualism gave women a chance to become influential public figures, and how they often used their positions as mediums to further the cause of suffrage. The thing I often find most challenging is trying to get at “the truth” of any woman’s story, particularly those from the ancient world. With women like Agrippina and Cleopatra, almost everything we know about them comes to us through other people; we don’t have ANYTHING that they wrote for themselves. I find it frustrating to only have the very edge of a story, unable to know for sure how much of that story has been shaped by the ancient men who told it. Though there’s fun to be had in that, too. These gaps allow me to get creative with the podcast, making up things these figures might have said. I’ve particularly enjoyed writing ancient Roman men’s dating profiles and giving ancient women witty retorts and killer one liners.

How do you define women’s history?

There are men out there who think my podcast and those like it aren’t for them. But women’s history is EVERYONE’S history. It’s just that instead of being told through the eyes and lives of men, as so much of history has been, it tries to give it to us through the women who lived it. Do I talk about periods and women’s fashion and childbirth and sex work on my podcast? Yes, and very much on purpose, because they are a part of our history—men and women—and to understand history, you can’t ignore them. I’m just trying to balance the field.

AND a question for you…

If you had to sum up one thing you learned from each of your books, Women Warriors and Heroines of Mercy Street – one central idea you took away about that time, or those women, or just women in history – what would they be?

In some ways, the two books are in conversation with each other. They are two different ways of looking at women in times of warfare.

Some of the first women warriors I learned about as a child were the women who disguised themselves as men to fight in the American Civil War. In writing Heroines of Mercy Street, I reached the conclusion that the women who volunteered as nurses in the war were far more important than the several hundred women who fought, no matter how bravely. That was true not simply for the work they did during the war, but for the impact they had on society after the war. I now believe that their work as reformers after the war is the most important part of their story.

Many used their newfound experience at organizing, and at elbowing their way through bureaucracies to help change the world. Cornelia Hancock, for instance, the young Quaker woman who found her way to Gettysburg, started a school for the children of former slaves in South Carolina. Other former nurses were active in building hospitals for women and children, reforming prisons and asylums, and providing vocational training for girls. They set up relief funds for war widows and orphans, and organized programs to settle unemployed veterans on farmland in the West. Some became active in the labor, women’s rights, and temperance movement. A few used their experience as a springboard to national leadership roles, founding groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the American Red Cross. If you look at an American reform movement in the 20 or 30 or even 40 years after 1865, local or national, large or small, the odds are you’ll find a former Civil War nurse or two in the middle of things–or in charge.

My work in Women Warriors solidified my sense that women who disguised themselves to enlist as men across the centuries are a fascinating side issue. The numbers involved are statistically insignificant in any given war. Which is not to say that looking at their stories isn’t important. The reasons that women enlisted disguised as men tells us a great deal about the economic and social constraints on women’s lives. But the main thing I came away with with a sense of amazement of how many examples of women warriors there are and how hard it is for us to acknowledge their presence.

Want to know more about Kate Jermain and The Exploress?

Visit her website, and listen to a few episodes while you’re there: https://www.theexploresspodcast.com/

Visit her other website: https://www.katejarmstrong.com/

Follow her on Twitter: @theexploresspod

Follow her on Instagram: theexploresspodcast

Visit her Etsy store for lady-centric merchandise: https://www.etsy.com/au/shop/theexploress

* * *

Come back tomorrow, when I’ll share a list of some of my favorite women’s history podcasts.