Roosevelt, Lindbergh, American Isolationism, and a Book Review

I must admit, I bagged Friday’s blog post. I simply wasn’t sure what I could write that was meaningful and/or appropriate in our current troubles. My inbox over the last week has been filled with carefully crafted statements of alliance or calls to action. Many of them are a nervous, well intentioned attempt to enter the difficult conversations in which many of us are now involved. The best of them are rooted in personal experience, offer a list of suggested actions, or look at a very specific angle of systemic racism. I don’t have anything meaningful to add to the conversation.(1)

But I am currently involved in a deep research dive on Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, the isolationist movement in the United States during the same period, and the challenges journalists faced in reporting both stories (and later reporting on World War II). It was uncomfortable reading even before the murder of George Floyd changed our collective conversation in tragic, powerful and important ways. It is more than uncomfortable now. At a minimum, I am reminded of the high cost of remaining silent.

I’ve decided that the best thing I can do with this blog is what I planned to do all along: share the books I’m reading and stories from the past, being a little more conscious of how current events echo stories from the past.

Take a deep breath, I’m going in.

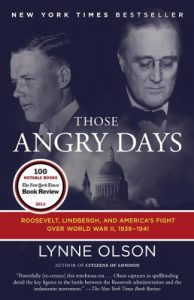

Several years ago I read Lynne Olson’s Last Hope Island with delight. Great storytelling. Impeccable research. Repeated moments of “I didn’t know that!!” When I learned that she wrote an earlier book on America’s struggles between isolationism and intervention in the years leading up to World War II I was thrilled. Those Angry Days: Roosevelt, Lindbergh, and America’s Fight Over World War II, 1939-1941 more than lived up to my expectations. (Note the liberal use of color-coded sticky tabs >  )

)

Olson explores how the issues of interventionism and isolationism split American society in the years before Pearl Harbor made those debates largely irrelevant. She centers the story on the larger than life figures who embodied the two positions: President Franklin Roosevelt and Charles Lindbergh. Neither man comes out looking good. Roosevelt often froze at the wheel: giving rousing speeches to the American public and then failing to take action for political reasons. Lindbergh, whom one journalist described as a “hypersensitive man who was insensitive to others,” translated his personal likes and dislikes into political positions,(2) with apparently little or no understanding of the larger context, and then used his celebrity status to push those positions. (In a spirit of full disclosure, the more I learn about Lindbergh, the less appealing I find him . Feel free to adjust for my distaste.)

But the story is more than a Clash of Titans. Olson takes us through the conflict in step-by-step detail, looking at grassroots activism as well as the actions of those in power. She introduces the reader to individual members of Congress who took positions on both sides of the conflict, bringing them to life in unexpected ways.(3) She looks at high-ranking officers in the American military who were anti-intervention and who actively worked to undermine Roosevelt’s pro-British policies. She outlines the workings of a covert British operation which created false news, dug up dirt on isolationist Congressmen, and helped form the OSS, precursor to the CIA. (Sound familiar? I refer you to my review of Agents of Influence.) She describes the formation and actions of isolationist groups like the America First Committee and the American Mothers Neutrality League and their interventionist counterparts, the White Committee (officially the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies) and the Century Group.

The one thing that is absolutely clear is that it was a dirty fight on all sides.

And yet, I came out with undiluted admiration for one player in the game.(4) Wendell Wilkie scuttled his own presidential campaign by supporting the passage of a contested conscription bill at the very moment that he accepted the Republication nomination to run against Roosevelt in 1940. When party members censored his action, he answered that he was “an American first, and a Republican afterward.” A hero by any standard as far as I’m concerned. And one we should all take as a model, regardless of our political persuasions.

1) Anyone who has been reading this blog for a while should have a clear sense that I am passionate about the need for diversity in our historical narrative. That passion is rooted in a deep belief in the importance of fighting for diversity, equality and inclusion. I doubt if it comes as any surprise that I am against police brutality and racism. And I am saddened by the fact that it is necessary for all of us to take a clear position because silence is complicity.

2) As do we all to some extent.

3) For example, the two ranking Republicans on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William Borah of Idaho and Hiram Johnson of California, who led the isolationist faction in Congress were both born shortly after the Civil War and couldn’t quite grasp the fact that the invention of warplanes and submarines meant that the United States was vulnerable to attack in a way that it had not been in their childhoods. Quite frankly, this made my jaw drop and led to several paragraphs of excited scribbling.

4) Two if you count Elizabeth Murrow, Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s mother. She only appears as a bit player, but she definitely caught my imagination.