Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Shelley Puhak

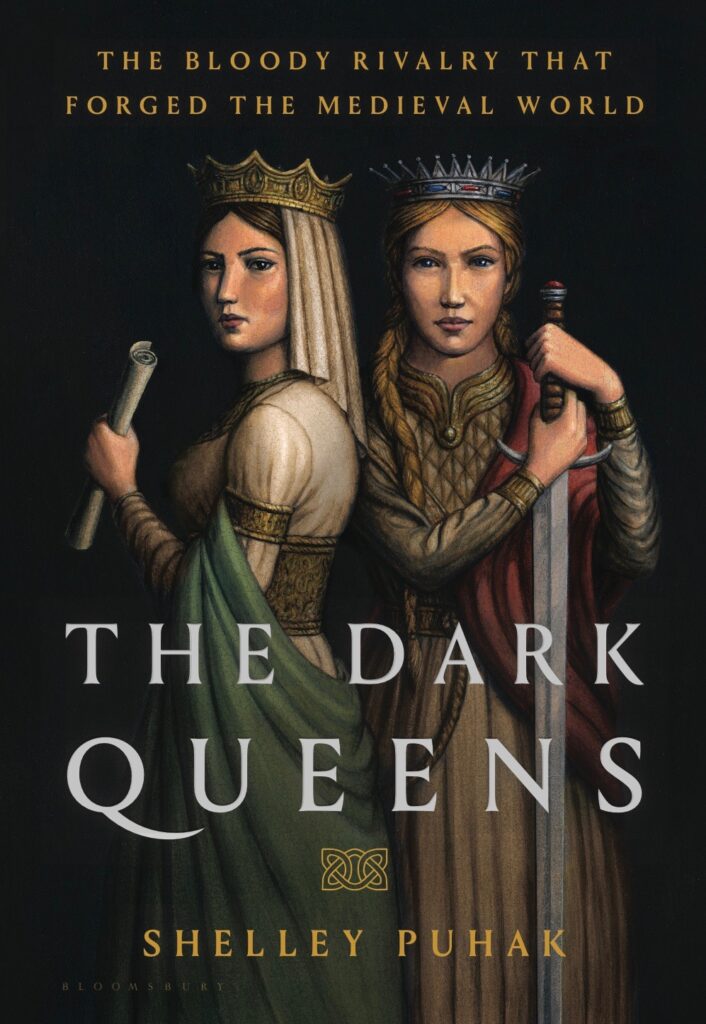

Shelley Puhak is the author of the newly-released The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry that Forged the Medieval World, a dual biography of the early medieval queens Brunhild and Fredegund. Shelley is also a former literature and creative writing professor and the author of three books of poetry, the most recent of which is Harbinger, a National Poetry Series selection.

I met Shelley (only virtually alas) back in September, courtesy of Nancy Marie Brown, who thought we would like each other’s books. As indeed we did. (Actually, I loved her book. Great story-telling, solid research and a significant amount of attitude at the way the two women at the center of her book were intentionally denigrated and effectively erased by their immediate successors and later chroniclers. Good stuff.) I immediately asked her to be part of this year’s Women’s History Month extravaganza here on the Margins.

Take it away, Shelley!

You are an award-winning poet. What inspired you to make the leap to writing a work of historical non-fiction?

You know, I think of it less as a leap and more as a lateral move. My previous books of poetry focused on lesser-known women’s lives and involved considerable research. For my book Stalin in Aruba, for example, I had to read diaries and memoirs and visit archives to be able to write in the voices of the women in Stalin’s inner circle, women like his daughter, sisters-in-law, and the wives of his close advisors.

I also write nonfiction, but prior to this just essays and articles. When I stumbled across the story of Brunhild and Fredegund, I first wrote an article about them for Lapham’s Quarterly. But I felt like the queens weren’t done with me yet. After all, we have yet to have a female head of state. Didn’t people deserve to know that during a time we think of as so much less sophisticated, women were ruling? In an attempt to get these two queens in front of as big an audience as possible, my project morphed into a book.

Brunhild and Fredegund are typically vilified in histories of the Merovingian period. You have turned them into rounded figures who were power players in the, admittedly blood-stained, politics of their times. Were there special challenges in bringing these women out of the historical shadows?

There are always challenges when trying to write about any women, and then there is the additional challenge of trying to write about anyone who lived 1,400 years ago. A major difficulty is the general lack of sources for the era. Some scholars estimate that what survives represents less than 1% of what was produced during that time period– loss on that sort of scale is staggering!

Some works were purposefully suppressed, but most vanished due to plain old bad luck. The Merovingians primarily used papyrus, and while that writing material can survive for tens of thousands of years in a dry climate like Egypt, it doesn’t make it more than a few centuries in the cold and damp of Europe. The sources that do survive are (surprise!) quite misogynist, and then each of these writers had his own individual biases and blindspots that I had to navigate. The research process was a lot like looking through a kaleidoscope— everything was scrambled, fractured, and distorted.

What are the most surprising things you’ve found doing historical research for The Dark Queens?

I was really surprised to discover how many women wielded power in the sixth century. I initially assumed that Brunhild and Fredegund were exceptions to the rule, but there were quite a few female political leaders. There were also women exerting power as abbesses and business owners and healers. We have wives walking out on their husbands, common women engineering political plots, and even nuns participating in armed rebellions. And given how many sources were lost, it is safe to say we don’t even know the half of it.

I was also startled to see how methodically Brunhild and Fredegund were silenced. It is one thing to know that women are often erased from history, and it is another thing altogether to see exactly how that happens. I had a really visceral reaction to reading, side-by-side, successive versions of a chronicle and seeing a few lines inserted here, a slur inserted there, something else conveniently trimmed out, over and over, until the original narrative was completely transformed. As chilling as that experience was, the flip side is a sort of awe at how women have, against the odds, managed to save some of their stories. Here’s one example: a very admiring account of Queen Fredegund’s military prowess survives in one anonymous chronicle. There are all sorts of theories about this chronicler’s identity, but it seems that Anonymous was (once again) a woman: circumstantial evidence links these tales to a nun at a local convent. I love to imagine that nun in her quiet cloister painstakingly preserving the battlefield exploits of a fierce queen. In other cases, these narratives might not have been written down right away but were instead told slant— embedded in a myth or a legend, for example. People will always find ways to resist.

A question for Pamela: Do you see your project about Sigrid Schultz of the Chicago Tribune as more of a continuation of your previous book (warrior to war reporter?) or a complete departure from it? Can you talk about how this research is similar to and different from your previous work?

I definitely see it as a continuation of my last three books, though Sigrid Schultz was a war correspondent for only a small part of her career. In Heroines of Mercy Street, I wrote about women in the American Civil War. In Women Warriors, I wrote about women in many different times and places who actually fought. Across the Minefields tells the story of a woman driver attached to the Free French in World War II. In When I began to look for a new subject, I was worried about pigeon-holing myself as someone who wrote only about women and war. In fact, I was deep in the initial research about a woman who had nothing to do with warfare when Sigrid Schultz elbowed her out of the way.

As far as the research goes, the current book is very different from my previous books. Both Heroines of Mercy Street and Across the Minefields rested heavily on the printed memoirs of a single character. (And both had seriously short deadlines, which made archival research impossible.) Women Warriors by its very nature meant I was dependent on secondary sources and translations of primary sources in languages I can’t read. Often the primary sources available in any language were sparse, not to mention heavily slanted. In the case of Sigrid Schultz, there is substantial archival material, with substantial gaps in the record. It’s been an adventure.

* * *

Want to know more about Shelly Puhak and The Dark Queens?

Check out her website: https://www.shelleypuhak.com/

Read her article in Smithsonian: The Medieval Queens Whose Daring Murderous Reigns Were Quickly Forgotten

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with independent scholar and art historian Eve Kahn, talking about forgotten American Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams.