Rock Island Arsenal, Part 1: Colonel Davenport’s House, and a Couple of Long Digressions

Visiting “Colonel” George Davenport’s house on the Rock Island Arsenal* turned out to be more interesting than I expected, in part because of our knowledgeable and enthusiastic guide. And also because it turned out that “Colonel” Davenport was right at the center of things in the history of the the region. Something I also hadn’t expected. (Somehow it didn’t dawn on me until our visit that the city of Davenport was named after him. *Duh*)

Davenport was a British sailor who came to the United States on a British ship in 1783, after the Treaty of Paris, which in theory resolved issues between Great Britain and its former colonies.** Shortly before the ship set sail from New York back to Britain, one of Davenport’s fellow sailors fell overboard. Davenport jumped in after him, breaking his own leg in the process. Because a sailor with a broken leg was of no use on board ship—and possibly an active liability—Davenport as left behind when the ship sailed.

Instead of finding his way back to Britain when his leg healed, Davenport decided to settle in the United States and joined the American army. He served for ten years, working his way up to sergeant. He served during the War of 1812, fighting against the British and mustered out at the war’s end.***

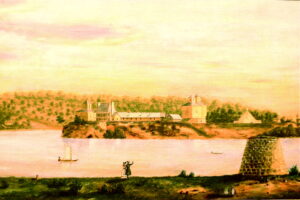

During the War of 1812, the American army lost two skirmishes with Native American allies of the British in the area of the Upper Rapids, a difficult part of the Mississippi River between the modern towns of Davenport and Le Claire.**** Concerned about continued relationships between the Sauk and Meskwaki peoples and Canada, the Army decided to build an outpost on Rock Island—a location that would allow them to command the Upper Rapids and give them easy access to both the Sauk city of Saukenak and two nearby Meskwaki villages.

Davenport accompanied the army as the post sutler: a civilian contractor responsible for providing the army and its builders with everything they needed. He also made a claim on a substantial amount of land on the island and built a log cabin for himself and his family. His wife Margaret and her two children from a previous marriage came with him. (As an aside: There is no proof that Margaret and George were married and lots of speculation about their relationship. He publicly acknowledged Margaret was his wife, but she was 14 years older than he was and Davenport openly had two sons with her daughter Susan. Lots of questions, no good answers. )

By the time Fort Armstrong was completed, Davenport decided it was time to move on to a more lucrative endeavor. He got a fur trading license and developed a network of posts that ranged from Galena down to southern Iowa and west to Des Moines, with his base at Rock Island.

When the Black Hawk Wars began in 1832, the governor of Illinois appointed Davenport quartermaster of the Illinois militia and gave him the rank of Colonel—no doubt for reasons that made sense to the governor. Despite the fact that the historic site is called the “Colonel Davenport house,” Davenport does not appear to have used the title after the war. Perhaps he agreed with Eddie Rickenbacker that you shouldn’t use a title you hadn’t earned.

In 1833, Davenport built the house that we toured, which is roughly contemporary to the house at the John Deere historic site. The most interesting thing about it as far as the architecture is concerned is that though it looks like a frame house, the main part of the house is a two story log cabin with clapboard siding. (Lumber was expensive on the frontier.)

In the meantime, things were changing in the territory around the Upper Rapids and Davenport was involved in all of it. He gave up his fur trading license and focused on trading with members of the growing white population in the region. He piloted the first steamship upriver through the Upper Rapids, helping open the northern section of the river to the steam boat trade. Then he sold cord wood to steamships heading up the Mississippi. He was instrumental in establishing the towns of Rock Island and Davenport. And he was one of the movers and shakers involved in founding the Rock Island Line: a 75-mile long railroad that linked Rock Island with Chicago.

Davenport did not live to see the railroad come to fruition He was murdered in his home on July 4, 1845. Drawn by rumors that he had at least $20,000 in his safe, several would-be thieves broke into the house during the 4th of July celebration in Davenport. They assumed the house would be empty. Unfortunately, Davenport was not feeling well and decided to stay home. The robbers shot him in the leg, and then forced him to open the safe. When they discovered that it contained only $400, they beat him unconscious and left him for dead, taking a few small valuables with him.

Davenport revived and lived long enough to give a description of his robbers before he died. Five men were captured and charged with his death.

* Just to make it clear, there are two Rock Islands in the Quad Cities area. One is the city of Rock Island, Illinois. The other, technically Arsenal Island, is the largest of three river islands in the area and home to the Rock Island Arsenal. Unfortunately, most people still call Arsenal island by its former name of Rock Island, leading to confusion among the uninformed.

**As is so often the case, the treaty left significant issues unresolved. Hence, the War of 1812.

***During the course of our visit, I found myself wondering whether Davenport ever became an American citizen. Our guide didn’t know, and on discussion we realized that neither of us knew how a person became a citizen in the first decades after the United States.

I knew from an earlier project that at the time the British defined an American as someone who lived in the thirteen colonies prior to 1783 or who was born there. They did not recognize the right of a British emigrant to become a citizen of a new country. (In other words, from the British perspective, Davenport remained a British citizen until the day he died.)

The United States recognized the need for a naturalization process almost from the start. Congress passed the first naturalization act on March 26, 1790. The act provided that any free, white, adult alien, male or female, who had resided in the United States for 2 years was eligible for citizenship and could apply for citizenship to any court of record. (The naturalization process was finally opened to African immigrants in 1870.)

None of which answers the question of whether Davenport became a citizen.

****One of those skirmishes occurred on Credit Island, so called because it was the place where French fur traders negotiated how much credit they would give Native American hunters in the fall against furs to be hunted over the winter, and where they later settled accounts with those hunters. A colonial relative of two addresses that caught my eye during a recent visit to an Atlanta suburb: Cashback Bonus Boulevard, near Credit Card Court. I cannot make these things up.

__________________

Traveler’s Tip:

The Davenport house is located on the Rock Island Arsenal, which is an active military base. You need a pass to get on base unless you have a military id. Take the bridge from Moline—not the bridge from Davenport—and follow the signs to the Visitor Control Center. You will need a valid state id or U.S. Passport.

Give yourself plenty of time. (As far as I’m concerned, this is always a good idea no matter what you’re doing.) There may be a line.