Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Elaine Hayes

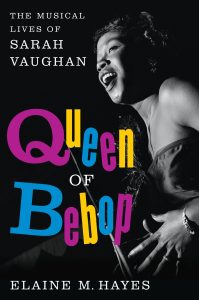

Elaine Hayes is the author of the critically acclaimed biography Queen of Bebop: The Musical Lives of Sarah Vaughan (Ecco, 2017). Recognized as a best book of the year by Amazon, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and the Washington Post, Queen of Bebop tells the story of this iconic vocalist’s rise from a choir girl in Newark, New Jersey, to an innovator at the forefront of modern jazz, a pop star, and ultimately a vocal legend, whose voice transcended boundaries of genre, race, and class. Elaine received her doctorate in musicology from the University of Pennsylvania and currently lives in Seattle with her husband, son, and Archie the miniature poodle.

I am thrilled to have Elaine here on History in the Margins on March 27, 2024, just in time to celebrate Sarah Vaughan’s 100th Birthday.

Take it away, Elaine:

When did you first become interested in big band “girl singers” and women in jazz? What sparked that interest?

Sarah Vaughan was my entry point into girl singers, big bands, and really, jazz more generally. I was a classically trained pianist, who hadn’t thought much about jazz until a college roommate played lots of Sarah Vaughan. I was immediately drawn to her voice, how she used it, and the sheer presence and authority she exuded when she sang.

I didn’t really know that much about Sarah the woman until a couple years later when, as a graduate student, I wrote a research paper about her for a seminar on women in jazz. I learned more about her artistry and creative process. The challenges she faced as a woman working in the male-dominated world of jazz. And how the narratives surrounding both her professional and personal life shaped her legacy. I realized that there was a bigger story to tell—one that would provide insights not only into Sarah Vaughan but also vocalist and women in jazz more generally.

Writing about a historical figure like Sarah Vaughan requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

Yes, Sarah Vaughan really did become my constant companion, first as a graduate student and then a decade later as her biographer. Spending five days a week, for years, thinking about a single person, investing in her life and career, triumphs and challenges, can be very intimate. Even though we never met, and I didn’t have a relationship with her in the traditional sense, I felt a close emotional bond. Vaughan’s power as an artist magnified this connection. She possessed an uncanny ability to capture the full spectrum of human experiences and emotions in her singing. And I, like so many other listeners, felt as if I knew her and she knew me.

I am not a sentimental person, but I cried as I wrote, and even edited, the final chapter and epilogue of Queen of Bebop. The life of a person who I admired and cared deeply about was ending, and so was my journey with her. There was a very real sense of mourning and loss.

As I re-visit the material for Vaughan’s centenary, however, it is speaking to me in a new way. It’s like reconnecting with an old friend that I hadn’t realized I’d missed. I’m enjoying their company again and remembering why we became friends in the first place.

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the early and middle twentieth century?

In the past 20 years, writing about a public figure like Sarah Vaughan has, in fact, gotten much easier. When I began the project as graduate student, it was hard to find source material. If I wanted to go beyond the clip folders collected by two or three specialized libraries, I needed to read full runs of publications—on microfilm! This was incredibly time consuming (and nausea inducing). So I limited myself to trade publications, how critics, usually white critics, responded to her singing. This really narrowed the story I could tell.

But now, thanks to the emergence of searchable digital newspaper and magazine archives, there is a wealth of source material. With patience, persistence, and perhaps most importantly, good organization, researchers can find amazing things.

This allowed me to reconstruct Vaughan’s career with a level of granularity and precision which had been missing. It also helped me incorporate perspectives that had been underrepresented or overlooked in past scholarship. A survey of the Black press, for example, added complexity to her story by providing insights into how Black communities understood Vaughan and her singing.

And, finally, because of these digital resources, I was able to re-insert Vaughan’s own voice back into her narrative. (Past biographers relied on contemporaries and acquaintances to tell her story.) When I began the project, I couldn’t find many interviews with Vaughan, and I assumed she simply did not give that many. This was not the case. Although she was a reluctant, often hostile interview subject, she regularly spoke to the press. By digging into this newly accessible historical record, I rediscovered many of these interviews, making it possible for Vaughan to tell us, in her own words, about her worldview and approach to making music. This was huge.

A question from Elaine: Now that I’ve told you about the wealth of source material I was lucky to find about Sarah Vaughan, I’m interested in learning more about how a historian like you, who does study women from the distant past, recreates their life stories.

In working on my last book, Women Warriors, I faced a number of challenges as far as sources were concerned.

Because it was a global history, I was dependent on secondary sources and translations of primary sources in languages I could read. (And mightily frustrated by the hints about sources that had not been translated.)

Even when I had access to sources, they were often meager. In the case of Boudica for instance, who led her people in a revolt against the Romans in 61 CE, we are limited to three written sources, with some help from modern archeology. All three written accounts are told from the perspective of her enemies. The Roman historian, Tacitus, who was born five years before the revolt, wrote two separate accounts of Boudica’s revolt. He could at least claim secondhand knowledge of the events on which he reported: his father-in-law served as a member of the Roman governor’s staff during the revolt, and there is evidence that Tacitus interviewed other veterans of the rebellion. Our only source is a fragment of an account written roughly a hundred years later by Dio Cassius, which appears in a a selection of readings compiled by a Greek monk in the eleventh century CE. With primary sources such as these, one must read and write warily.

My current book is a different story. There is a great deal of material by and about its subject, Sigrid Schultz, the Chicago Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief from 1925 to 1940. And even so there are holes I was not able to fill.

***

Interested in learning more about Elaine Hayes’ work on Sarah Vaughan and other women of jazz?

Check out her website: https://elainemhayes.com/

Follow her Facebook page: Sarah Vaughan, Queen of Bebop

***

Come back tomorrow for a whole lot of questions with novelist Vanessa Riley.