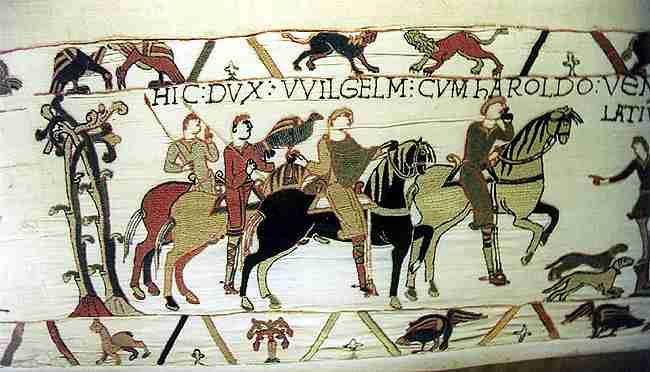

With the Bayeux Tapestry in the news….

The Bayeux Tapestry is in the news right now. The French President has committed to loaning Britain the tapestry at some time in the future: the equivalent of an InterLibrary Loan between nations. I must admit, when I first heard something about this I was only halfway paying attention. My first reaction was "Oh, no! We're going to Normandy this spring. Will it be gone?" (Moral of the story: listen to the news or turn it off.)

Since then, I've enjoyed some interesting commentary on the tapestry and the possible loan, including this issue of the HistoryExtra podcast and this New Yorker article.

I don't have enough brain width right now to add anything meaningful to the conversation. But you might find this post on the Battle of Hastings, generated after a trip in 2012, useful.

Image courtesy of Antonio Borillo

On October 13, thousands of history enthusiasts from around the world arrived at the British town of Battle to re-enact the Battle of Hastings. (You know, William the Conqueror, 1066, and all that.)

My Own True Love and I weren't there.* Just as well. The weather was cold and wet. The battlefield conditions were so muddy that the organizers called off the second day of the battle because the ground was too muddy for vehicles to get in and out. (I suspect any number of Anglo-Saxon and Norman soldiers at the original battle would have been pleased if someone had called off the second day of the real battle.)

When we arrived, a week later, the battlefield was still a muddy mess. We happily went through the excellent introductory exhibit, learning about Anglo-Saxon England, the Duchy of Normandy, and why William the Bastard of Normandy** thought he had a claim to the English crown.***

Then we headed to the battlefield, audio tours in hand. Before we got to the first point on the tour, we were slipping in the mud on the path. My Own True Love's shoes sprang a leak. Defeated by the mud, we retreated to the café, where we drank coffee, listened to our audio tours, and envied the rubber boots worn by the squadrons of British school children trooping past.

You can get a detailed account of the battle here. These are the elements that struck me:

- Both sides were descendents of Viking conquerors. The rulers of England were the descendents of King Canute of Denmark. The Normans were Norwegian Vikings with a French accent.

- The battle was a classic stand off between infantry and armed horseman: immovable object vs. irresistible force.. The English army, on foot, depended on the strength of its shield wall. The Normans enjoyed the mobility of cavalry. William stumbled on a tactic that the Mongols (armed horsemen par excellence) would later use to confound Western armies. When his men panicked and retreated, exultant English troops broke out of formation to pursue them. William saw what was happening and ordered his flank to cut the English off. The pursuers were surrounded and slaughtered.. The first time was an accident. William learned; apparently the English didn't. When William ordered a feigned retreat to replicate his success, the English pursued again and were slaughtered again.

- The Battle of Hastings changed history, but it wasn't the only time France invaded England. Who knew?

Next stop, Brighton.

* We missed several special history nerd events as we drove along Britain's southeast coast--always a week too late or a week too early. We did, however, manage to arrive in Bath on the day of a major rugby match.

** The name was a legal description, not a character assessment.

*** William was a shirttail relative to Edward the Confessor, whose death in 1066 was the catalyst for the invasion. William's great grandfather was Edward's maternal grandfather.

From the Archives: In Search of Hiawatha

Just so there is no confusion here, the several months ago referred to below happened in 2013. Over the next five (eeek!) weeks, as my book deadline draws nigh I may resort to re-running old posts more often than usual.

Several months ago, on a visit to Fort Michilimackinac, I was startled to read an exhibit sign that referred to Hiawatha as a real person.

As far as I knew, Hiawatha was the fictional hero of a Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem: "By the shore of Gitche Gumee" and all that. On the other hand, as I thought about it I realized that much of what I know about Paul Revere also comes from a Longfellow poem. Perhaps Longfellow's mythical Indian chief wasn't so mythical after all and I was the only one who hadn't caught on.

When I finally got a chance to poke around, I discovered that the question of Hiawatha, Longfellow, and reality is a complicated one. I immediately found that there was indeed an historical, or at least semi-mythical, Hiawatha. He was a leader of the Onondaga (or possibly Mohawk) tribe who was one of the founders of the Iroquois Confederacy in the 16th (or possibly 15th) century, depending on who you read. Further research, however, made it absolutely clear that the historical Hiawatha was not the subject of the Longfellow poem

In the 1850s, Longfellow set out to write what he described as an "Indian Edda": an epic poem combining Native American themes with a structure and "primitive"* meter borrowed from the Finnish epic, the Kalevala.** He found his local material in large part in the ethnological writings of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. An Indian agent in the western wilds of Michigan whose wife was half-Ojibwe, Schoolcraft collected Native America lore, was the first to translate Native American poetry into English, and was a serious student of Native American religious legends.

Longfellow loosely based his story on Schoolcraft's account of an Ojibwe trickster-hero named Manabozho. Somewhere along the way he decided to change the name to Hiawatha, stating in his journal that it was "another name for the same personage". *** Obviously the confusion was Longfellow's, not mine.

I feel so much better.

* His term, not mine. If it makes the occasional Finnish reader feel any better, he also described the Kalevala as "charming".

** Itself a nineteenth-century creation, assembled from pre-Christian Finnish songs and folk tales by folklorist Elias Lönnrot in the early 1830s. The twisty relationship between national identity and folk culture is fascinating--and a topic for another day.

*** To be fair, some of my sources blame this confusion on Schoolcraft. I'm not prepared to track this down further. Take your choice.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

From the Archives: Lovelace, Babbage and Steampunk Comics (with a little grumble about Lord Byron)

Today is the 230th birthday of George Gordon, Lord Byron, and bits of his history are popping up here and there all over the internet. There are lots of good (or bad) stories to tell. He was a poet when poets were rock stars of the sex, drugs and iambic pentameter variety. And he was the baddest, bad boy of them all. But I'm not going to spend any time telling them. Byron was one of the central figures in my dissertation, which given that I got my doctorate on the twenty-year plan means he was part of my life for far too long. In my opinion, he was a jerk. But then, I never had a taste for bad boys.

Instead, I'm gone back into the History in the Margins archives for a post about a clever steampunk comic about Byron's daughter, Ada Lovelace. Enjoy!

Normally when I use the phrase "comic-book history" here on the Margins I'm referring to the shorthand popular version of history that we learned as children and carry in our hearts as adults: Abraham Lincoln dashing off the Gettysburg address on the back of an envelope, the first American Thanksgiving, Marie Antoinette's infamous line "let them eat cake--like that. These historical anecdotes are at best incomplete versions of history and at worst absolutely wrong, but they are emotionally satisfying so they live on no matter how often they are debunked.*

Today, though, I'm going to talk about a real comic book, described by its author as "an imaginary comic about an imaginary computer.": The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer.

Sydney Padua starts out with two real people:

Augusta Ada King (1815-1852) , the Countess of Lovelace, better known as Ada Lovelace. Daughter of the famous (and infamous) Lord Byron, Lovelace was a talented mathematician. Most women with that skill in her time would have had no opportunity to use it. Lucky for her, her mother insisted that she be educated in a rigorous program of math and science well outside the norm for young women of the time, hoping such study would counteract any poetical tendencies she might have inherited from her father. ** (In case you're not up on nineteenth century gossip, it was a spectacularly unhappy marriage.)

Augusta Ada King (1815-1852) , the Countess of Lovelace, better known as Ada Lovelace. Daughter of the famous (and infamous) Lord Byron, Lovelace was a talented mathematician. Most women with that skill in her time would have had no opportunity to use it. Lucky for her, her mother insisted that she be educated in a rigorous program of math and science well outside the norm for young women of the time, hoping such study would counteract any poetical tendencies she might have inherited from her father. ** (In case you're not up on nineteenth century gossip, it was a spectacularly unhappy marriage.)

Charles Babbage (1791-1857) was an irascible and inventive mathematician and tinkerer who is often called the "father of the computer". He designed two machines intended to automate complex calculations: the difference machine and the later, more complicated analytical engine.

Charles Babbage (1791-1857) was an irascible and inventive mathematician and tinkerer who is often called the "father of the computer". He designed two machines intended to automate complex calculations: the difference machine and the later, more complicated analytical engine.

Lovelace was fascinated by his work. When asked to translate an Italian engineer's article on the analytical machine into English, she added her own notes to the piece*** in which she described how code could be written that would expand the use of the machine. Making her the first computer programmer. At least in theory.

Padua tells the history of Lovelace and Babbage in twenty-five smart, snarky, footnoted pages--then revolts against the fact that history gives her characters unhappy endings.**** The rest of the smart, snarky, footnoted comic takes place in an alternative steampunk universe where Lovelace and Babbage "live to complete the analytical engine and use it to have thrilling adventures and fight crime." Padua takes elements of nineteenth century history (Luddites, for example) and historical personages (Queen Victoria among them) and twists them into unhistorical forms that are nonetheless historically illuminating. It's quite a trick and makes me think of Marianne Moore's definition of poetry as the ability to create "real toads in imaginary gardens".

*My apologies to those of you who have heard this rant before, either here or In Real Life.

**This seems to have been based on a fundamental lack of understanding of the poetical properties inherent in higher mathematics and the amount of imagination required to make scientific leaps.

***Three times the length of the original article.

****Lovelace had a drug habit, tried (unsuccessfully) to use her mathematical skills to build a gambling system, and died young of uterine cancer. Babbage, being irascible, was in constant fights with just about everyone and never built his analytical engine. In part because he was in constant fights with just about everyone.