Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Vicky Alvear Shechter

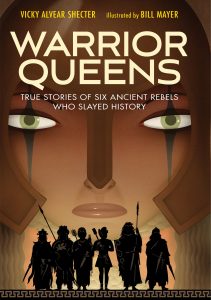

Vicky Alvear Shechter has been on my radar since the days when we both contributed posts to the late, lamented group history blog Wonders and Marvels.* When I learned that she had written a book titled Warrior Queens, which introduces pre-teens to little-known ancient queens who took up arms against invaders and enemies, it was an automatic pre-order.

Vicky writes fiction and nonfiction about the ancient world for kids and adults. Her novels include the award-winning Cleopatra’s Moon and Day of Fire: A Novel of Pompeii. Her latest nonfiction release is Warrior Queens: True Stories of Six Ancient Rebels Who Slayed History. Vicky has also served as a docent for more than twelve years at the Carlos Museum of Antiquities at Emory University.

Who better to head off this year’s series of Women’s History Month? Take it away Vicky!

You write both historical fiction and historical non-fiction. Is your research process different for fiction than for non-fiction?

The research process for fiction and non-fiction is about the same, though the difference is in the level of obsession! LOL. For nonfiction, because of the stakes, I try to find multiple sources to back up a claim, whereas for fiction, if one reliable scholarly source makes a claim and it’s a detail I can use, I am more apt to consider weaving it into the story without hunting down corroboration in the way that I would for nonfiction.

Here’s an example: When I was writing my novel set in Pompeii (Curses and Smoke: A Novel of Pompeii), I read about graffiti in the city. Again and again I found references to graffiti that warned passers-by to “not to defecate here.” I remember thinking, oh my gawd, there was a public defecation issue in Pompeii? I even found one reference to a sign, posted by a magistrate outside a gate that said, “Dear Shitter, Hold it In Until You Pass this Area.”

I mean, that is hysterical! If I were writing nonfiction about this, I would confirm these signs by location on the city walls and by consensus translations from the Latin. And I would probably spend quite a bit of time recreating how that must have looked and smelled at the time, as well as use that information to discuss ancient attitudes toward elimination and bodily functions. It would then lead to a discussion of public toilets, how one wiped (with a sea sponge attached to a stick, shared by everyone!), etc., etc.

But when it came to writing the novel, I could only slip this detail into the story in passing. Why? Well despite that I personally found it hysterical, my main character would not find this kind of graffiti unusual. Also, if I made a big deal about the fact that she had to dodge people taking craps in the street when she went outside, then I unconsciously create a fear in the reader that she might “step in it” at some point. Since that option would’ve been a distraction rather than part of the story, I had to minimize this fascinating (and very funny) historical detail.

If you could pick one woman from history to put in every high school history textbook, who would it be?

That would have to be Queen Amanirenas of Nubia, who I write about in Warrior Queens: True Stories of Six Ancient Rebels Who Slayed History. I would want every kid to know about her because she took on Rome at the height of its powers and won!

Yet no one knows about her. Indeed after fighting and defeating Roman legions who dared try to invade her territory from Egypt after the fall of Cleopatra, Amanirenas negotiated a treaty with the most powerful man in the world—Octavian Caesar (later known as Augustus Caesar) and got everything she demanded! That’s pretty incredible!

She was a bad a** in so many ways. She lost an eye in battle leading her army against the Roman incursion into her cities. And when she retook one of her cities, she toppled a bronze statue of Augustus, had it beheaded, and marched back to her palace with the head. Then she buried it under the walkway in her palace so she would walk all over him every day! This bronze head was dug up under her palace and is one of the most recognizable busts of the young Roman emperor in the world.

How could you not love a woman so fearless and protective of her nation and its people?

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

Because I focus on women of the ancient world, the challenge is working with a lack of written material about powerful women. Both Greek and Roman cultures were deeply misogynistic and women’s stories were rarely considered let alone written about. So, for example, the story of Amanirenas mentioned above, shows up as only one paragraph in Strabo’s work. He mentions her victory in passing as if it had been no big deal, yet it was huge. Admitting to being bested by a woman was deeply embarrassing so her story is downplayed and mentioned as an aside.

The exciting part is realizing that we can analyze the lens through which women’s stories are told. For example, the Romans depicted Queen Cleopatra, the last pharaoh of Egypt, as a hyper-sexual femme fatale type, a wanton woman who put Marc Antony under “her spell.” When in reality Cleopatra had only two relationships her whole life, which she treated as marriages—one with Julius Caesar and one with Marc Antony. She was the mother of four children—a son with Julius Caesar and two sons and a daughter with Marc Antony. (I tell the daughter’s story in my novel, Cleopatra’s Moon).

She was also politically brilliant: she kept Egypt independent of Rome for twenty years, despite the mistakes of her father who put Egypt in deep debt to greedy Roman senators. She spoke seven languages and was considered a religious leader of larger Egypt in a way that former Ptolemaic (Greek) kings never could.

And yet, even today, we envision Cleopatra as highly “sexy” and beautiful when even Plutarch describes her as somewhat ordinary looking but whose charm, intelligence, and personality won over everyone in her presence. Also, she is depicted as shamefully abandoning Antony yet Plutarch reveals that she was asked several times to hand over her husband to Octavian with promises of keeping her throne but she always refused.

Finally, from Shakespeare on, Cleopatra is always depicted as a lovesick woman who kills herself right after Antony’s death. In reality, she waited three weeks after capture before she killed herself. Why? Plutarch says that during those weeks, Caesar pounded her with threats to her children as if “with siege engines.” He had already killed her first born.

As a mom, I understood instinctively what she was doing those three weeks. She was fighting for and negotiating for the lives of her remaining three children. At some point, she must have realized she had to remove herself in order to save their lives, so she did. And Octavian saved the remaining children, bringing them back to Rome with him. (The daughter was the only one to survive and later ruled a north African province as queen). [Pamela butting in here: What????!!!]

Seeing past the lens of their propaganda, we can see beyond the “sexification” of her reputation and glimpse a more complex, savvy, and brilliant political leader.

Question for you: You’ve written about so many brilliant women throughout history. Which one do you wish more people knew about and why?

My answer to this question probably depends on the day you ask. But for today, my answer is Matilda of Tuscany. (1046-1115). She was a major player in the most important political and theological issue of her time, the Investiture Controversy, which was an ugly struggle between emperor and pope that was ostensibly over who would control appointments to religious offices and was at root over the relationship between secular and religious power.

Matilda’s appearance in history books, to the extent that she appears at all, is generally limited to one incident, known as the Humiliation at Canossa. In 1077, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV arrived as a penitent at her fortress at Canossa to petition Pope Gregory VII for absolution. It’s a dramatic incident, complete with the emperor dressed in sackcloth, standing barefoot in the snow, and begging for admission to the fortress for several days. When Matilda appears in accounts of the event, her role is often limited to that of a peacemaker.

In fact, the Humiliation of Canossa was one brief moment of peace in the Investiture Controversy. Matilda, the peacemaker of Canossa, provided the main military support for Gregory and his successors in their struggles with Henry for the next twenty years and became the secular rallying point for the reform cause after Gregory’s death.

Over the course of a forty-year military career, Matilda mustered troops for long-distance expeditions, fought successful defensive campaigns against the Holy Roman emperor (himself a skilled commander), launched ambushes, engaged in urban warfare, directed sieges, lifted sieges, and was besieged. She built, stocked, and fortified castles. She maintained an effective intelligence network. She negotiated alliances with local leaders. She rewarded her followers with the favorite currencies of medieval rulers: land, castles, and privileges. In short, she did everything that her male counterparts did, with the handicap of being female in a time when elite women were often little more than political poker chips in the hands of their male relatives.

Interested in learning more about Vicky Alvear Shecter and her work?

Check out her website: www.vickyalvearshecter.com.

Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/valvearshecter

*It’s no longer being updated, but the archived articles are still available to read, and they are indeed wonderful and marvelous. Just click the hot-link. But only after you read the rest of this post.

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historian Theresa Kaminski, who has some fascinating projects underway, including a biography of Civil War surgeon and ardent reformer Dr. Mary Walker, due out on June 1st. Mark your calendars.

P.S. Women Warriors is now out in paperback, in case you missed the news.