1920: A Year in Review

If you spent time this year in the places where the history buffs hang out on-line, including this blog, you know that the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified on August 18, 1920— “giving” women the right to vote. Over the course of 2020, historians expanded the story to remind us of two important things. Women fought hard for that right; no one gave it to them. And women of color still had a long fight before them, one which isn’t completely over.(1) It’s been fascinating watching the revision of history, in the best sense, happen in real time.

If you spent time this year in the places where the history buffs hang out on-line, including this blog, you know that the 19th Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified on August 18, 1920— “giving” women the right to vote. Over the course of 2020, historians expanded the story to remind us of two important things. Women fought hard for that right; no one gave it to them. And women of color still had a long fight before them, one which isn’t completely over.(1) It’s been fascinating watching the revision of history, in the best sense, happen in real time.

Obviously the 19th Amendment wasn’t the only thing of importance that happened in 1920. Someone might even make the case that it wasn’t the most important thing. (Though that someone wouldn’t be me.) Here are some other high points, low points, and things that caught my imagination:

In related news, Oxford allowed women to take degrees for the first time.

In the United States, the Roaring Twenties were getting ready to roar:

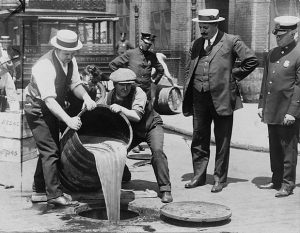

- A waste of good beer?

- General Thompson with his gun

- Flappers +jazz+radio

- The 18th Amendment, which prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors…” was ratified on January 16. In order to put some teeth in the amendment, Congress passed the Volstead Act on October 28, which provided for its enforcement. Prohibition didn’t stop Americans from drinking, it just made it illegal and gave organized crime something to get organized about.

- Prohibition-related turf wars were more violent than they might otherwise have been, because that year General John T. Thompson patented and began production of the iconic Thompson submachine gun.(2) Thompson had invented the gun during the First world War, intending it as a replacement for the bolt-action rifles then in use, but the war ended two days before the prototypes were ready to ship. Without a war in progress, the gun was originally marketed to police departments as “the safest gun to shoot on city streets” and the “anti-Bandit gun.” Bootlegging mobsters also saw the advantage to a gun that was perfectly designed for close-up shootouts on the street. The gun was expensive—half the cost of a new Ford—but the only people that stopped were cash-strapped police departments. In Chicago, you could legally rent a Tommy gun at your local hardware store.

Despite the gun’s notoriety, sales were slow because the man in the street didn’t need an expensive submachine gun. (And still doesn’t, in my opinion.) The Thompson submachine gun finally came into its own in World War II, when more than half a million Thompson submachine guns went into battle in the hands of American soldiers.

- On a more positive note, the first commercial radio station opened on November 2 in Pittsburgh. And I do mean commercial. The Westinghouse, which was a leading radio manufacturer, came up with programming as an innovative way to sell more radios. Radio began as a form of one-to-one communication between individual radio operators. Westinghouse hoped that programming would reach an audience that wasn’t interested in learning to operate a radio. The company reached out to a Pittsburgh-area ham radio operator named Dr. Frank Conrad who frequently played records over the airwaves to entertain his ham radio friends. The company asked Conrad to help them set up a regularly transmitting station with programmed content. On November 2, KDKA in Pittsburgh made its first broadcast. (Conrad was the one who chose the term to describe the new form of radio.) The day was carefully chosen to prove the power of radio: it was election day and listeners were able to hear the results of the Harding-Cox presidential race before it appeared in the newspaper. (3) Westinghouse may have pictured the radio as a source of news, but it turned out that listeners wanted entertainment. Within a decade, most American homes had a radio.

Outside the United States:

- First meeting of the League of Nations

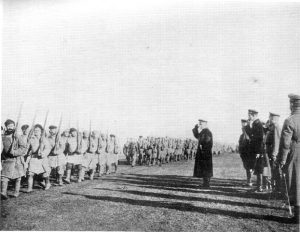

- Red Army on parade

- A White army volunteer brigade (Am I the only one curious about the woman?)

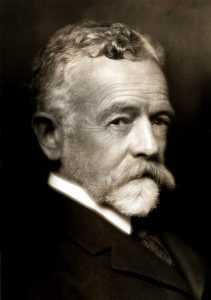

- The Covenant of the League of Nations went into effect on January 10. The League held its first meeting in Geneva in November. By the end of the year, 48 countries had joined the League. The United States was not among them. The Senate voted against joining, thanks to the arguments of Henry Cabot Lodge, who worried that joining the League would force the United States into foreign wars.(4) Isolationism was on the way.

- The Russian Civil War, which broke out in 1917 after the Russian Revolution, ended in victory for the Bolshevik Red Army. The Bolsheviks successfully defended their new government against the White Army, a loose alliance of monarchists, capitalists and supporters of democratic socialism led by former officers of the Tsarist army.

- In March, a 62-year-old civil servant named Wolfgang Kapp and a cabal of German army officers attempted to overthrow the Weimar Republic and establish an autocratic government—a failed attempt known as the Kapp Putsch (5) Even though it did not succeed, it was a telling statement about political conditions in German. The republic government was new, uncertain, and a tempting target for anyone who didn’t like government by the people.

- On November 21, the events known as Bloody Sunday(6) marked a decisive turning point in the Irish War of Independence. In the morning, an IRA squad(7) killed twelve British intelligence agents and two auxiliary police officers and wounded others in a series of attacks across Dublin. In the afternoon, British policemen, suspecting that the gunmen were part of the crowd at a football match, blocked all the exits to the park. Their instructions were to search the thousands of spectators attending the match. Within minutes, for reasons that are not clear, (8) the police began shooting into the crowd. Fourteen people were killed or fatally wounded—included three schoolboys and a woman who was supposed to be married a few days later. Dozens more were injured. The total death count for the day was “only” 30—a small number compared to the hundreds killed in the Amritsar Massacre the year before. The anger unleashed by the day’s events was unmeasurable.

There are a lot of questions raised by this event—the fine line between freedom fighter and terrorist, the mindset that causes policemen to fire into unarmed grounds,(9) the fact that the more I learn about the British empire the harder it is to maintain my lifelong Anglophilia. This already too long round-up post isn’t the right place to consider them, though I may struggle with them in coming issues of my newsletter. (10)

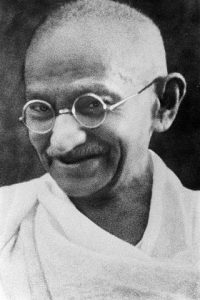

- And speaking of the British Empire behaving badly: In September, Mohandas Gandhi, now the undisputed leader of the Indian National Congress,launched his first nationwide non-violent non-cooperation (satyagraha) campaign in India, using techniques he had developed in South Africa. He urged Indians to boycott not only British products, but British institutions, including schools, courts, honorary titles, and taxes. Gandhi called off the campaign in February, 1922, when an angry mob murdered police officers in a village in Uttar Pradesh.(11) The non-cooperation movement failed to win self-rule, or even concessions, from the British government of India but it helped transform Indian nationalism from an elite club to mass national movement.

- Henry Cabot Lodge

- Wolfgang Kapp

- No introduction required

In short, 1920 was a hopping year.

(1) It’s amazing how many of my political heroes of 2020 are women of color.

(2)Before it officially became the Thompson submachine gun, the company called it the Annihilator and the Persuader—possibly not the image a company wants when selling to government purchasing departments, though good for marketing to mobsters. On the street, it was known by names like the Chicago Typewriter, the Chicago Piano, the Chicago Organ Grinder, and the Street Sweeper. You probably know it as the Tommy gun.

(3) The battle between newspapers and radios over who had the right to tell the news was soon to become a big deal and was only resolved when radio broadcasters began to report live in WWII. But I digress.

(4) He also seems to have really hated Woodrow Wilson. I leave you to judge for yourself how big a role that played in his policy positions. After all, he seems to have hated a lot of people and ideas.

(5) For those of you who share my desire to pronounce this like putz, putsch rhymes with butch. Despite the fact that Kapp seems, in fact, to have been a putz.

(6) Not to be confused with the Bloody Sunday of January, 1904, which kicked off a series of insurrections in Imperial Russia, though both involved armed policemen firing on peaceful crowds.

(7) Autocorrect insists this should be a squad of IRS agents, but as far as I know the Internal Revenue Service does not carry out assassinations no matter how badly someone cheats on his taxes.

(8)Revenge? Panic?

(9)A hot issue for our times, with deep historical roots. A quick glance through the History in the Margins archives reveals that I’ve written about instances when policemen or soldiers have fired on unarmed crowds more than once, ranging in time from the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 to the Bonus Expeditionary Force’s march on Washington in 1932. (I’ve also spent some time thinking about the role of mounted policemen.) Each story is an ugly incident when looked at alone. Looked at together, they make a horrifying statement about the use of power.

(10) A few weeks ago I once again had a blog reader say: “Oh, I didn’t know you had a newsletter, too.” I suspect I also have newsletter readers who don’t know I have a blog. Because I apparently do not know how to cross promote them. So, for those of you who don’t know: I also have a more-or-less bi-monthly newsletter in which I struggle with the problems of writing history, as opposed to telling stories from history. If that is your slice of pie, you can sign up here: http://eepurl.com/dIft-b

(11) This is the flip side of police officers firing into crowds. The danger that can be posed by mobs is a real thing that needs to be part of the discussion. Because these are not simple questions.