From Trench Warfare to Trench Coat? *duh*

I was happily taking notes about the transformation of the Chicago Tribune’s Army Edition into that paper’s Paris Edition in the years after World War I —a subject I’ve spent quite a bit of time on during the last couple of years. I wasn’t expecting to learn much that was new, but I have kept the library book as long as the generous policies of the Chicago Public Library will allow and I wanted to capture any information I might need going forward.*

Then I read these words: “money-making ads for woolen underwear, trench coats, and portable bathtubs.” I had clearly read them before because I had marked the section with a sticky note. And yet, this time it hit me. Trench coats. Trench warfare. And once again, I was off down the research rabbit hole.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term “trench coat” first appeared in 1914. And there is no doubt that the trench coat evolved into the form we know it today during World War I, when British officers wore it, well, in the trenches. But it wasn’t entirely new.

The first ancestor of the trench coat appeared in 1820, when an English inventor named Thomas Hancock and a Scottish chemist named Charles Macintosh treated long cotton coats with rubber and marketed them as “macks”. They were not entirely successful. The same characteristics that kept rain out kept sweat in. The rubberized material was smelly even before it got sweaty, and it had a tendency to melt in the sun. Even with those drawbacks, “macks” were popular with military officers and the huntin’ and fishin’ set who wanted to stay dry.

Inspired by the obvious market for waterproof outdoor wear, textile manufacturers continued to develop better materials. By the mid-1850s, two manufacturers, Aquascutum and Burberry, had succeeded in developing fabrics that both repelled water and breathed and used them to create high-end gear for outdoor sports. The Burberry fabric, known as gabardine, proved particularly successful. (One Burberry’s ad for a waterproof gabardine fishing suit touted its “practical impermeability to wet, cold winds, and fish hooks.”) Unlike other waterproof materials, it was made by coating the thread prior to weaving rather than coating the completed fabric. Gabardine outerwear was popular with aviators, explorers and adventurers as well as outdoorsmen. When Sir Ernest Shackleton went to Antarctica in 1907, his team wore Burberry coats and carried tents made of Burberry gabardine.

When the first Anglo-Boer War began in 1899, many British officers unofficially adopted Burberry’s knee-length gabardine coat in place of the regulation wool great coat, which were long and heavy. Half-way through the war, Burberry became an official supplier to the British Army and created a coat made to military specifications: the Tielocken. It looked a lot like the classic trench coat, complete with a double breasted front and a tied waist belt.

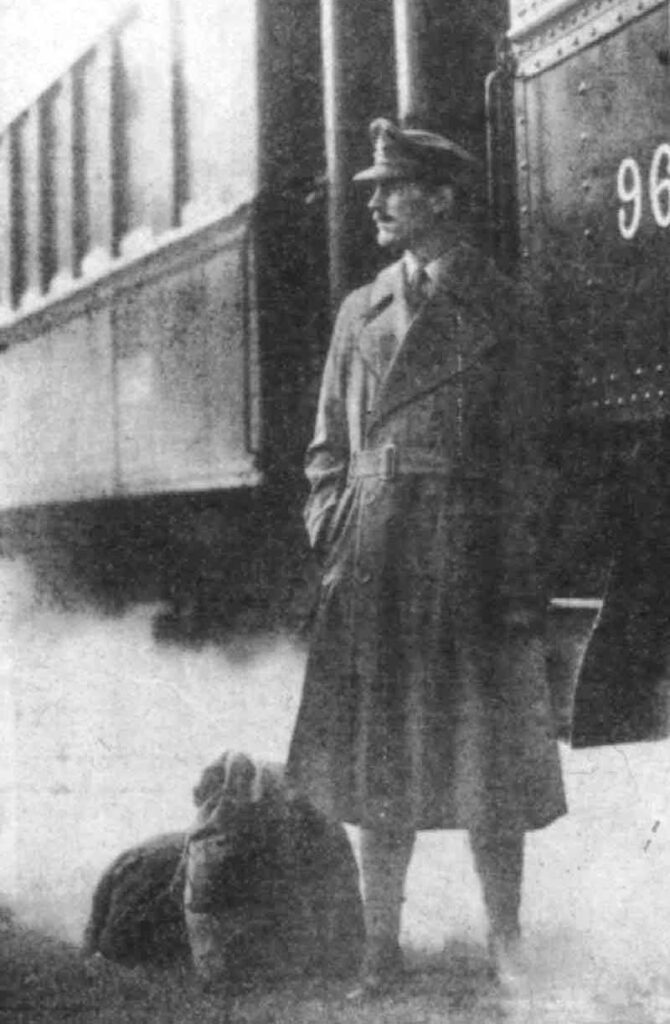

By 1914, the Tielocken had evolved to meet the needs of trench warfare.** It was short enough that it wouldn’t trail in the mud, with a slightly flare below the belted waist that made it easy to move in. The belt had D-rings to hook accessories on, It had a small cape across the shoulders that allowed water, to drip off, large deep pockets to hold maps, flasks, and other necessities, and and cuffs that could be tightened for further protection. Some coats had a removable liner, that could serve as bedding in a pinch. And just in case anyone forgot that the trench coat was an officer’s prerogative, straps across the shoulders were a convenient place to display epaulettes with the rank of the wearer.

Swashbuckle, anyone?

*For anyone who’s interested, the book is Ronald Weber’s News of Paris: American Journalists in the City of Light Between the Wars. It is both well-researched and delightful to read. For my purposes, it has lots of details about being a working journalist in the 1920s and 1930s and vivid sketches of some of the men who crossed Sigrid Schultz’s path.

** Or at least the needs of officers. Enlisted men were still issued the traditional wool great coat, which was warm but badly designed for trench warfare. In fact, men often cut off the bottom of the coats so they wouldn’t drag in the mud. Rank also had its disadvantages. Once the German realized that trench coat meant officer the distinctive silhouette made it easier for snipers to pick them off.