Belva Lockwood: a guest post by Jack French

Once or twice a year, long-time friend of the Margins Jack French reaches out with an interesting story and an offer to share. I’ve learned to say yes. Whether it’s the woman who invented Monopoly, a pair of WASP pilots, or a book recommendation, it’s always worth reading, and it’s often appropriate for Women’s History Month. He’s back, with another story of a woman I hadn’t heard of before. (I can’t tell you more without spoilers.)

Take it away, Jack!

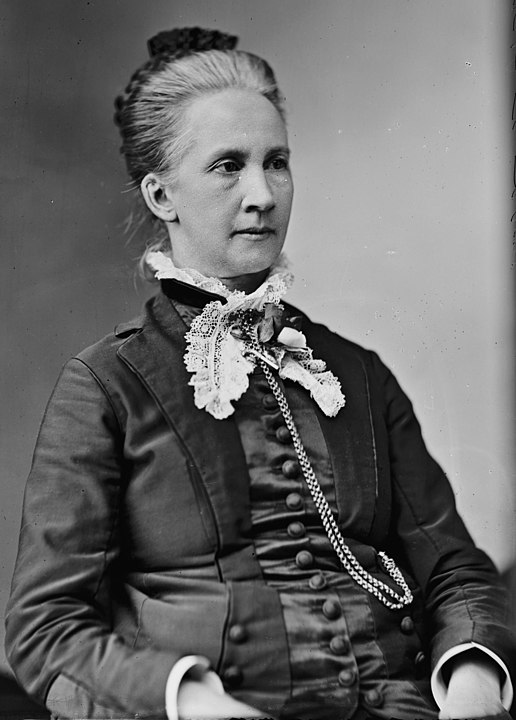

Belva Ann Bennett was born October 24, 1830 into a modest farm family in Royalton, NY. Her parents apparently had a penchant for quirky names as two of Belva’s four siblings were named Cyrene and Inverno. In that pre-Civil War era, women were barred from nearly all professions (medicine, law, dentistry, banking, federal employment, etc.) but Belva would rise from her humble beginnings to become the first woman lawyer to argue in the Supreme Court and also the first woman to legitimately run for U.S. president….twice!

Despite her ambitions as a teenager, Belva was virtually limited to three options: domestic service, teaching, or getting married. She originally chose the latter two. At age 14 she accepted a teaching position, where she resented being paid half of what her male counterparts received for doing the identical work. In 1848 she married Uriah McNall, four years her senior.

The couple were farmers and also ran a small mill. They had one daughter before her husband died of injuries from a mill accident. The young widow sold the mill, and now, convinced that education would improve her lot, enrolled in college in Lima, NY, graduating in 1857. However she then had difficulty in finding a suitable position and was forced to accept a teaching job, again at half the salary of male teachers.

Later she became acquainted with both Susan B. Anthony and Dr. Mary Walker, and Belva would remain a champion of women’s rights as long as she lived. Anthony convinced her to move to Washington, DC for better prospects. By then Belva had aspirations of becoming a lawyer. In the Nation’s Capital, she met and married Ezekiel Lockwood in 1868. A 65 year old dentist, he was four years older than her father. But he was a loving husband and fully supported her quest for a law career. They resided in D.C. and operated a rental agency.

After being turned down at several East Coast law schools because of her gender, Belva fortunately found a new law school locally which admitted women on a limited basis: the National Law University in D.C. (which years later would merge into George Washington University.) In early 1871, National Law University accepted 15 women as students, but only two of them would eventually graduate: Lydia Hall and Belva Lockwood. However the institution refused to award them their diplomas.

Both successfully passed the three day exam (oral and written) for the D.C. bar, but since they had no diplomas, they were not admitted. Belva boldly wrote a personal letter to President Ulysses Grant, who was the honorary president of the university, requesting her diploma be released to her. It worked. Two weeks later her law diploma was in her hands and she was admitted to the D.C. bar on September 24, 1873, the second woman to achieve that distinction. The first was Charlotte Ray, the daughter of a nationally prominent African-American minister and publisher. She was admitted to the D.C. bar in 1872, shortly after graduating from Howard University Law School. However so few people would engage a woman of color as their attorney, Ray had to give up her practice and become a teacher.

Lockwood was moderately successful in her law practice, but some of her cases required argument in the Court of Claims, which had a separate bar. It would take Belva years of struggle to achieve that goal. Although she succeeded in getting a hearing to the bar of Court of Claims, it was a painful experience. After a lengthy discussion before a panel of five judges, she was told by the presiding judge: “Mistress Lockwood, you are a woman!” Later Belva would write: “For the first time in my life I began to realize that it was a crime to be a woman, but it was too late to put in a denial and I at once pleaded guilty to the charge.”

After weeks of deliberation the bar association concluded “A woman is without legal capacity to take the office of attorney” and therefore her request for admission was denied. However Belva was not to be stopped. She poured over the Supreme Court’s rulings on such matters, one of which concluded that any attorney in good standing before the highest court of State or Territory for three years shall be admitted to that court when presented by a member of the bar. But when the three years were up for her, she was still denied bar admission unless there was legislation for such approval. During this time, Ezekiel died in April 1877, leaving her a widow again.

But Belva then became a lobbyist in her own behalf. She located friendly faces in Congress, gave speeches, found allies in the press, and uncovered weak spots in her opposition. Her two year relentless campaign was successful. The bill admitting women to the Supreme Court bar was signed into law on February 7, 1879. Three weeks later, she became the first woman to be admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court.

Her astonishing victory opened the legal doors to all women in local, state, territory, and federal courts. Elizabeth Cady Stanton extolled her triumph, dubbing her a true “Portia”, Shakespeare’s brilliant lady lawyer. Her legal business continued to thrive. Very late in life she would be on the team whose arguments in the Supreme Court resulted in a multi-million dollar award for the Cherokee Nation.

In 1884 she consented to be the Presidential nominee for the Equal Rights Party, thus becoming the first woman to run for that office. “I can’t vote, but you can vote for me” was one of her slogans. Some of the press treated her fairly but others preferred lampooning her in cartons. She lost to Grover Cleveland, but four years later she ran again, this time defeated by Benjamin Harrison.

She continued her legal practice and pushed for women’s suffrage until she died at the age of 86 in 1917, just three years short of being able to vote. Sadly, the history books have ignored her, despite her impressive accomplishments. As her biographer, Jill Norgren, explains, there is “…a preference in history for Founding Fathers and fighting generals…”

PRIMARY SOURCES:

Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would be President by Jill Norgren, (New York University Press, 2007)

“Struggles and Accomplishments of Belva Lockwood” (2011) by Maryann Freedman, https://buffaloah.com/h/lock/lock.html

Jack French is a researcher, feminist, and author in Northern Virginia; his website is: http://www.jackfrenchlectures.com/ His book, Private Eyelashes: Radio’s Lady Detectives (Bear Manor Media, 2004) won the Agatha Award for Best Non-Fiction and was voiced as a Talking Book by the Library of Congress.

Jack French is a researcher, feminist, and author in Northern Virginia; his website is: http://www.jackfrenchlectures.com/ His book, Private Eyelashes: Radio’s Lady Detectives (Bear Manor Media, 2004) won the Agatha Award for Best Non-Fiction and was voiced as a Talking Book by the Library of Congress.

***

Women’s History Month isn’t over yet! Come back on Monday for Three Questions and an answer with Julia Scheeres, co-author of Listen, World!

Thank you so much Jack French and of course Pamela. The synopsis was very interesting so I went immediately to the Maryann Friedman link to read about her there. I am certainly accumulating a growing file on the topic of women in general…..of which I have in the past titled about ten, The Women who….most of them from America, but some who started it all in Europe. I will continue to forage and unearth with your help.