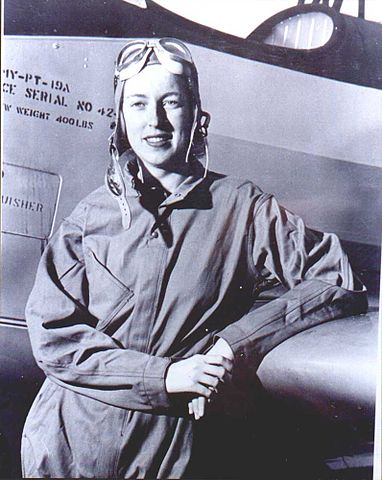

Cornelia Fort: Eyewitness to Pearl Harbor

Cornelia Fort was a certified civilian flight instructor who worked for the Andrews Flying Service in Honolulu, a Nashville debutante who had kicked her way into the male dominated world of general aviation. (1) She was only 22 and already an experienced pilot with hundreds of flight hours to her credit.

On December 7, 1941, Fort was in the air with a student pilot, a defense worker named Suomala who was practicing landings prior to taking his first solo flight. As was typical at the time, they had no radio, so the only way to avoid other aircraft coming and going at Honolulu's John Rodgers Airport was to scan the sky around them

Prior to what was scheduled to be Suomala's final landing before soloing, Fort scanned the sky. She saw a military plane heading in from the ocean. She was so accustomed to military traffic from the nearby military bases that she nodded to Suomala to turn into the first leg of his landing pattern. She looked again and saw another military aircraft headed right for them. She grabbed the controls away from her student, jammed the throttle open, and pulled above the oncoming plane. It passed under them, so close that their celluloid windows rattled.(2)

Fort glanced down to see what kind of plane it was. Instead of the insignia of the US Army Air Corps, painted red balls shone on the wings in the morning sun: the "rising sun" emblem of the Japanese. With a chill tingling down her spine, she looked west to Pearl Harbor, where she saw billowing black smoke and formations of silver bombers. Something detached itself from one of the planes and she watched as the bomb fell and exploded in the middle of the harbor.

She landed the plane at John Rodgers as quickly as she could, surrounded by machine gun fire. As they touched down, Suomola asked "When am I going to solo?" (Fort later said she wasn't sure whether he didn't understand what was happening or was trying to lighten the situation with humor.) A contemporary newspaper account reported her answer as "Not today, brother." A few seconds later, the shadow of a plane passed overhead and bullets spattered around them. Pilot and student sprinted for the cover of the hanger.

Once inside, Fort tried to warn others that the Japanese were attacking. She was met with disbelief and laughter. The men she worked with tried to pass it off as some sort of maneuvers that she had misunderstood. Fort was "damn good and mad.”(3) She was about to tell them off when a mechanic from another hanger ran in and told them that strafing planes had just shot another pilot and his student as they ran for cover.

As scores of Zeros roared by, some no more than fifty feet off the ground, Fort and her companions took shelter in the hangar. When she examined her plane the next day, she found it riddled with bullets.

Newspapers soon picked up the story of Fort's encounter with the Japanese--it would have been a good story no matter who was involved. But a pretty young female aviator gave it an additional human interest element. For a time, she was part of the speaking tour that sold war bonds. But she was determined to use her flying skills for the war effort. Lamenting the fact that she she couldn't be a fighter pilot and face the Japanese in the air again, she was the second woman to volunteer for the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS).

For several months she delivered small training planes(4) up and down the east coast. In February, 1943, Fort and several other WAFS was assigned to Long Beach California to deliver the much larger BT-13s. They were thrilled with the "promotion" to larger planes, but some of them remained frustrated by the fact that they were not allowed to become fighter pilots. Determined to acquire some of the skills needed, Fort and a few of her companions began to experiment with formation flying, an activity that was forbidden during delivery flights. On March 21, 1943, while participating in a forbidden stint of formation flying on a delivery, Fort's plane was destroyed in a mid-air collision, making her the first WAFS pilot to die while on duty.

What a waste.

(1) Her father made her brothers promise never to fly. He never thought to ask for the promise from his daughter. Her brothers were royally pissed off when they found out she had been taking flying lessons in secret.

(2) Fort's written account of the incident claims that at this point she felt "a distinct feeling of annoyance that the Army plane had disrupted our traffic pattern and violated our safety zone." My guess is that she swore like a fighter pilot--or at least gave vent to a string of the "dangs" and "sssssss--sugars" that passed for profanity among women of the Middle South at the time.

(3) And can you blame her?

(4) PT-19s, for the aviation fans among the Marginalia

1818: A Year in Review

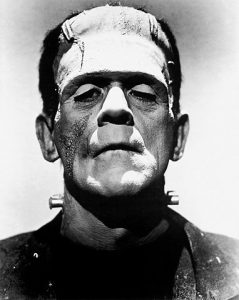

The year 1818 began and ended with the introduction of two very different works of art, both of which have become a permanent part of the popular culture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published on January 1st. On Christmas Eve, in the small Austrian village of Oberndorf bei Salzburg, young curate Joseph Mohr and schoolteacher/organist Franz Xaver Huber wrote Silent Night. *

The year 1818 began and ended with the introduction of two very different works of art, both of which have become a permanent part of the popular culture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published on January 1st. On Christmas Eve, in the small Austrian village of Oberndorf bei Salzburg, young curate Joseph Mohr and schoolteacher/organist Franz Xaver Huber wrote Silent Night. *

Some other high (or low) points of 1818:

- Elisha Collier and Artemis Wheeler received patent for a repeating flintlock pistol, with a five-shot cylinder in both Britain and the United States. Their design didn’t take off in the American market, but had some success in Britain. Despite the fact that you’ve never heard of them, Collier and Wheeler helped shaped their world. In 1830, one Samuel L. Colt filed for a patent based on their designs. His mass-produced revolvers were prized weapons in the American Civil War and the handgun of choice in the American west. More important in the bigger picture, he paved the way for the interchangeable parts system of manufacturing.

- Congress adopted the flag of the United States as having thirteen red and white stripes, representing the thirteen original colonies, and one star for each state. (There were twenty at the time,)

- The Convention of 1818 settled the border between Canada and the United States at the 49th parallel.

- In India, the British East India Company defeated the Maratha Empire. Officially subordinate to the crumbling Mogul empire, the Marathas had dominated the Indian subcontinent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1818) was the final and decisive conflict between the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire. The British victory left the East India Company in effective control of most of India.

- In Africa, Shaka united the Zulu nation. Under his leadership, the Zulu would become the dominant military force in the Natal region of South Africa.

- Karl Marx was born: not a big event in itself.

*I must admit, I took a moment to search for a clip of Frankenstein singing Silent Night, which seemed like it should surely exist. I found nothing, but I offer the idea to any of you with video skills.

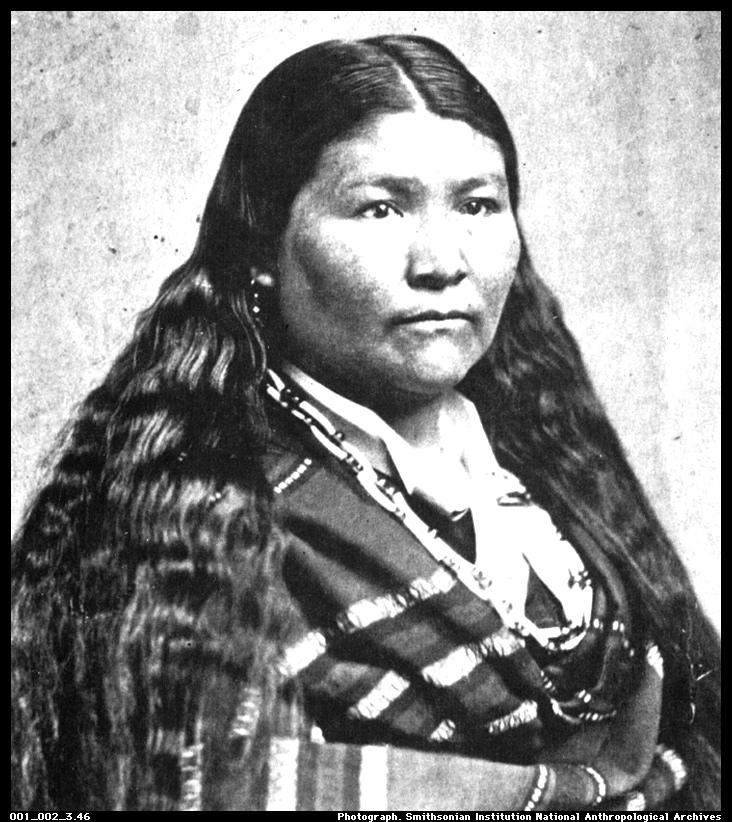

Toby Riddle: “Pocahontas of the Lava Beds” ?

Last week I was stunned to read this tweet from the Women’s History Museum of California:(1)

Toby Riddle was one of the first Native American women acknowledged by US Congress for her actions in time of war. In 1891 Congress granted her a pension of at “the rate of twenty-five dollars per month” for her courage in battle during the Modoc War.

I stopped and stared at it. I may have even shrieked “What?” Then, like any good history bugg, I went looking for the bigger story.

First a little context for those of you who, like me, are unfamiliar with the Modoc War of 1872-73. The Modoc nation historically lived in the region that what is now the border between Oregon and Washington. The movement of white settlers into the area in the 1840s resulted in conflict, with bloodshed on both sides. In 1864, under pressure from white settlers, the United States government decided to move the Modoc onto the Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon. It was not an obvious choice. The Modoc and the Klamaths were historic enemies and a number of Modoc refused to stay moved and returned to their old homes. The government sent Federal troops to move them once again.(2) Between 1867 and 1871, the Modoc tried to negotiate. In 1872, when negotiations failed, again, a Modoc Indian chief named Kintpuash, aka, Captain Jack, led several Modoc bands in an unsuccessful attempt to maintain his people’s independence. For some eight months, Kintpuash and no more than 53 Modoc warriors held off almost 1000 members of the United States Army.

Toby “Winema” Riddle (ca. 1850-1920) was a member of the Modoc nation. (And, incidentally, a cousin of Kintpuash.) She and her husband, a white settler named Frank Riddle, served as interpreters and facilitated negotiations between the Modoc and the U. S. Army throughout the late1860s. When war broke out, she became a messenger between the Modoc and U.S. Officials—a role made possible not only by her facility in both languages but by her relationship with Kintpuash

In February 1873, President Grant formed a peace commission to end the Modoc War, led by General Edward Canby. Once again the Riddles served as mediators, often under dangerous conditions..

Toby is best known for having warned Canby about a Modoc plot to kill him and the other peace commissioners at their next meeting. Canby ignored her warning and insisted on holding the meeting, set for Good Friday, April 11, 1873.

When Kintpuash arrived at the meeting, he was still willing to negotiate with the commission despite pressure from his fellow Modoc to proceed with the plan to kill the commissioners. Canby came to the meeting determined to force the Modoc to surrender and move back to the Klamath reservation. Tempers rose on both sides, despite Toby’s attempts to mediate. When it became clear that the meeting was about capitulation rather than negotiation, the Modoc fired on the peace commissioners. Canby and another member of the American negotiating team died. A third member of the commission, the former superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon, Reverend Alfred. B. Meacham, was wounded. Toby prevented him from being scalped by yelling to his attackers that the soldiers were coming.

The death of the peace commissioners made national and international headlines. Toby was hailed as the Pocahontas of the west (3) and an Indigenous Florence Nightingale.

The war continued for two more months, with the Modoc besieged in the natural fortress of what they called the Land of Burnt-Out Fires, now Lava Beds National Monument. Kintpuash was the last to surrender.

The Riddles later served as witnesses during the trial of six Modoc warriors involved in the death of the commissioners, including her cousin Kintpuash. They were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. In a particularly gruesome/racist epilogue, Kintpuash and another leader were posthumously beheaded and their heads sent to the Smithsonian for study. The remaining Modoc were removed to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma.

Meacham later wrote an embellished account of Toby’s life, naming her Wi-ne-ma, which he said meant “woman-chief”—a stage name she used when she traveled as part of his short-lived touring lecture company.(4) He also successfully petitioned Congress to give her a military pension for “prov[ing] herself to be the friend of the white man at the risk of her own live.”

In 1891, Congress granted her a pension of $25 a month for the rest of their life.

Today the Winema National Forest in Oregon is named after her.

(1) An institution deserving a blog post of its own.

(2) If this story sounds familiar, it’s because the pattern played out over and over again in the nineteenth century.

(3) A phrase with so much baggage attached that I don’t have room to unpack it here.

(4) Meacham, who knew little of Modoc language, took the name from a poem by poet and frontiersman

Joachin Miller (1837-1913). (Known as the “poet of the Sierras”, his real name was Cincinnatus Hiner Miller. ) This has echoes of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s fabricated language and legends about Lake Itasca in Minnesota.