1818: A Year in Review

The year 1818 began and ended with the introduction of two very different works of art, both of which have become a permanent part of the popular culture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published on January 1st. On Christmas Eve, in the small Austrian village of Oberndorf bei Salzburg, young curate Joseph Mohr and schoolteacher/organist Franz Xaver Huber wrote Silent Night. *

The year 1818 began and ended with the introduction of two very different works of art, both of which have become a permanent part of the popular culture. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was published on January 1st. On Christmas Eve, in the small Austrian village of Oberndorf bei Salzburg, young curate Joseph Mohr and schoolteacher/organist Franz Xaver Huber wrote Silent Night. *

Some other high (or low) points of 1818:

- Elisha Collier and Artemis Wheeler received patent for a repeating flintlock pistol, with a five-shot cylinder in both Britain and the United States. Their design didn’t take off in the American market, but had some success in Britain. Despite the fact that you’ve never heard of them, Collier and Wheeler helped shaped their world. In 1830, one Samuel L. Colt filed for a patent based on their designs. His mass-produced revolvers were prized weapons in the American Civil War and the handgun of choice in the American west. More important in the bigger picture, he paved the way for the interchangeable parts system of manufacturing.

- Congress adopted the flag of the United States as having thirteen red and white stripes, representing the thirteen original colonies, and one star for each state. (There were twenty at the time,)

- The Convention of 1818 settled the border between Canada and the United States at the 49th parallel.

- In India, the British East India Company defeated the Maratha Empire. Officially subordinate to the crumbling Mogul empire, the Marathas had dominated the Indian subcontinent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-1818) was the final and decisive conflict between the British East India Company and the Maratha Empire. The British victory left the East India Company in effective control of most of India.

- In Africa, Shaka united the Zulu nation. Under his leadership, the Zulu would become the dominant military force in the Natal region of South Africa.

- Karl Marx was born: not a big event in itself.

*I must admit, I took a moment to search for a clip of Frankenstein singing Silent Night, which seemed like it should surely exist. I found nothing, but I offer the idea to any of you with video skills.

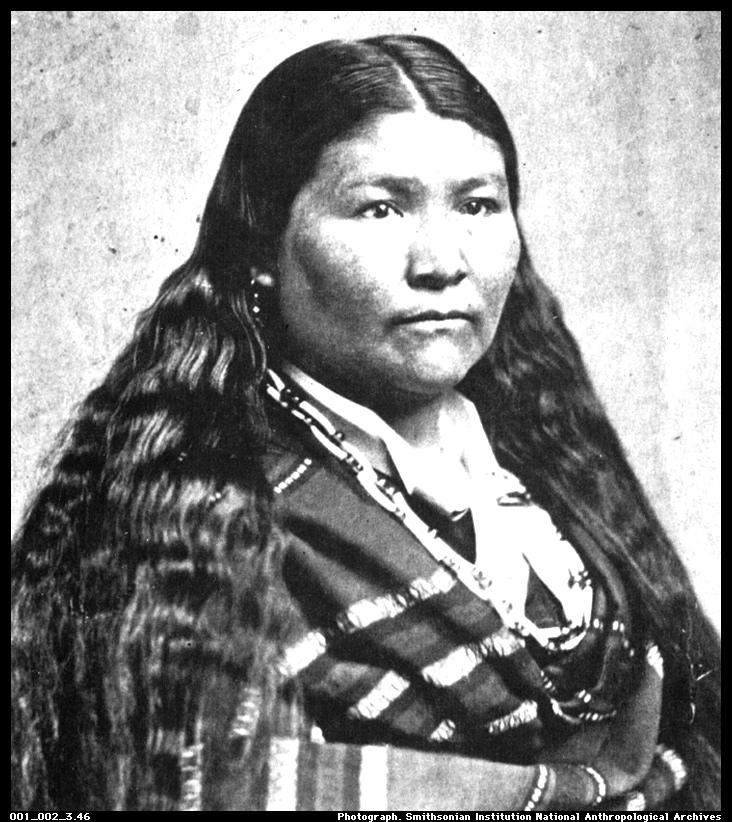

Toby Riddle: “Pocahontas of the Lava Beds” ?

Last week I was stunned to read this tweet from the Women’s History Museum of California:(1)

Toby Riddle was one of the first Native American women acknowledged by US Congress for her actions in time of war. In 1891 Congress granted her a pension of at “the rate of twenty-five dollars per month” for her courage in battle during the Modoc War.

I stopped and stared at it. I may have even shrieked “What?” Then, like any good history bugg, I went looking for the bigger story.

First a little context for those of you who, like me, are unfamiliar with the Modoc War of 1872-73. The Modoc nation historically lived in the region that what is now the border between Oregon and Washington. The movement of white settlers into the area in the 1840s resulted in conflict, with bloodshed on both sides. In 1864, under pressure from white settlers, the United States government decided to move the Modoc onto the Klamath Reservation in southern Oregon. It was not an obvious choice. The Modoc and the Klamaths were historic enemies and a number of Modoc refused to stay moved and returned to their old homes. The government sent Federal troops to move them once again.(2) Between 1867 and 1871, the Modoc tried to negotiate. In 1872, when negotiations failed, again, a Modoc Indian chief named Kintpuash, aka, Captain Jack, led several Modoc bands in an unsuccessful attempt to maintain his people’s independence. For some eight months, Kintpuash and no more than 53 Modoc warriors held off almost 1000 members of the United States Army.

Toby “Winema” Riddle (ca. 1850-1920) was a member of the Modoc nation. (And, incidentally, a cousin of Kintpuash.) She and her husband, a white settler named Frank Riddle, served as interpreters and facilitated negotiations between the Modoc and the U. S. Army throughout the late1860s. When war broke out, she became a messenger between the Modoc and U.S. Officials—a role made possible not only by her facility in both languages but by her relationship with Kintpuash

In February 1873, President Grant formed a peace commission to end the Modoc War, led by General Edward Canby. Once again the Riddles served as mediators, often under dangerous conditions..

Toby is best known for having warned Canby about a Modoc plot to kill him and the other peace commissioners at their next meeting. Canby ignored her warning and insisted on holding the meeting, set for Good Friday, April 11, 1873.

When Kintpuash arrived at the meeting, he was still willing to negotiate with the commission despite pressure from his fellow Modoc to proceed with the plan to kill the commissioners. Canby came to the meeting determined to force the Modoc to surrender and move back to the Klamath reservation. Tempers rose on both sides, despite Toby’s attempts to mediate. When it became clear that the meeting was about capitulation rather than negotiation, the Modoc fired on the peace commissioners. Canby and another member of the American negotiating team died. A third member of the commission, the former superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon, Reverend Alfred. B. Meacham, was wounded. Toby prevented him from being scalped by yelling to his attackers that the soldiers were coming.

The death of the peace commissioners made national and international headlines. Toby was hailed as the Pocahontas of the west (3) and an Indigenous Florence Nightingale.

The war continued for two more months, with the Modoc besieged in the natural fortress of what they called the Land of Burnt-Out Fires, now Lava Beds National Monument. Kintpuash was the last to surrender.

The Riddles later served as witnesses during the trial of six Modoc warriors involved in the death of the commissioners, including her cousin Kintpuash. They were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. In a particularly gruesome/racist epilogue, Kintpuash and another leader were posthumously beheaded and their heads sent to the Smithsonian for study. The remaining Modoc were removed to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma.

Meacham later wrote an embellished account of Toby’s life, naming her Wi-ne-ma, which he said meant “woman-chief”—a stage name she used when she traveled as part of his short-lived touring lecture company.(4) He also successfully petitioned Congress to give her a military pension for “prov[ing] herself to be the friend of the white man at the risk of her own live.”

In 1891, Congress granted her a pension of $25 a month for the rest of their life.

Today the Winema National Forest in Oregon is named after her.

(1) An institution deserving a blog post of its own.

(2) If this story sounds familiar, it’s because the pattern played out over and over again in the nineteenth century.

(3) A phrase with so much baggage attached that I don’t have room to unpack it here.

(4) Meacham, who knew little of Modoc language, took the name from a poem by poet and frontiersman

Joachin Miller (1837-1913). (Known as the “poet of the Sierras”, his real name was Cincinnatus Hiner Miller. ) This has echoes of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s fabricated language and legends about Lake Itasca in Minnesota.

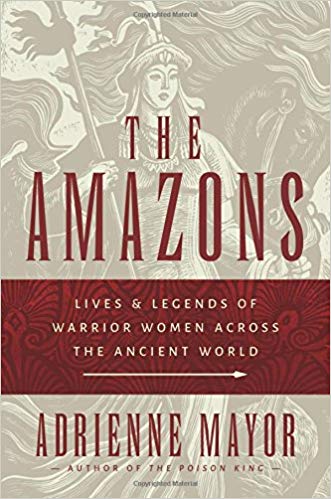

In which I finally review Adrienne Mayor’s The Amazons

Over the last year and a bit, I’ve mentioned Adrienne’s Mayor’s The Amazons more than once here on the Margins, always with a quick note to the effect that a) it’s excellent and b) I really need to review it. (1)

In some ways a review here is superfluous. A lot of you may have already read The Amazons . When it was published in 2014, Mayor had reviews, articles, and interviews in pretty much all the places an author of serious non-fiction would like to have her book mentioned. Since then she has become the go-to expert for both the legendary Amazons and the real-life Scythian warriors who may well have been the model for Herodotus’s account. (2) Her work is even the basis for a delightful animated Ted-Ed program.

And yet, and yet, you could say that for me it’s personal. Mayor’s The Amazons was one of a handful of books that I returned to again and again as I wrote first the proposal for Women Warriors and then the book itself, not only for information about ancient Scythia and classical Greece but also as a model for thinking and writing about the bigger issues in my book.

Here goes:

In The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World, historian Adrienne Mayor leads the reader on a breathtaking exploration of the women warriors of the ancient world. Working with myth, ancient historical sources, and modern archaeological finds, she draws the links between story and history, making a strong argument for the nomadic armed horsewomen of the ancient steppes as the model for the Amazons of myth. She ends the book with the quick look at ancient women warriors across the Eurasian steppes from the Caucasus, though Central Asia and into China. The Amazons is both scholarly and readable—not as easy to pull off as you might think. If you're interested in women warriors or the ancient world, add it to your to-be-read list.

Mayor’s newest book Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines and Ancient Dreams of Technology just came out. I can hardly wait to read it.

(1) Search the archives by Adrienne for the best results.

(2) If you want to see her in action, I suggest you check out the excellent Scythian episode in Smithsonian Channel’s brief and uneven series on women warriors.